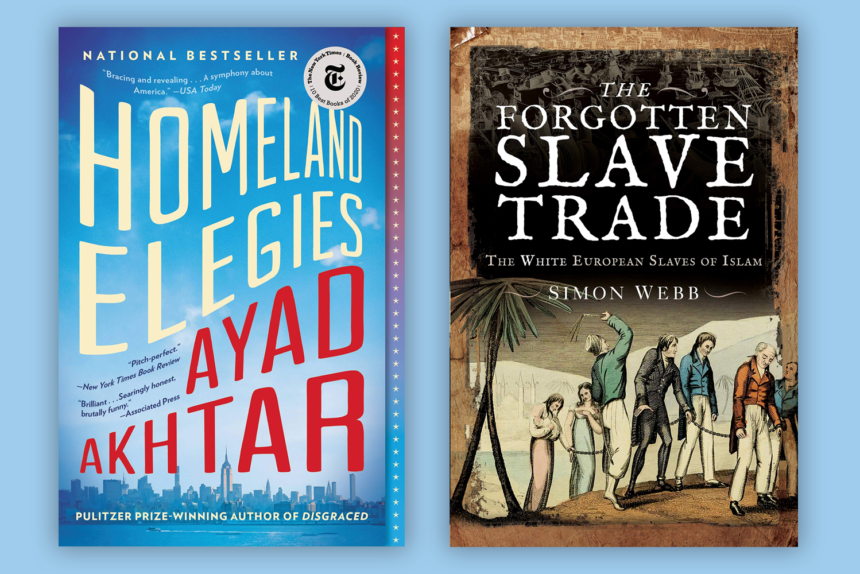

Homeland Elegies: A Novel, by Ayad Akhtar (Little, Brown & Co.; 368 pp., $28.00).

Mark Twain wrote in his 1897 travel book, Following the Equator: “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.” That saying came in handy as I read this book, described on its jacket as “part family drama, part social essay, part picaresque novel.” I couldn’t distinguish truth from fiction as I read this saga of the roller-coaster relationship between an immigrant Pakistani cardiologist and his American-born literary son. If reality limits fiction’s realm of possibility, then this book must be truth, despite its title’s contrary claim.

Let’s look at the evidence. Incest remains one of the last sexual taboos in the West. Akhtar, however, nostalgically recalls his native Pakistani mother’s lifelong sadness after her youthful crush married his second cousin. Later while living in Houston, the father of Akhtar’s girlfriend tried to arrange her marriage to a first cousin in Pakistan. Following Twain’s maxim, it’s because these scenarios stretch credibility that they ring true.

The American elite preach that only whites commit racism. So it must not be fiction when Akhtar mentions his “disgust for white bodies,” his humiliating encounter with a “bone-white” Pennsylvania state trooper, and his father’s legal accuser whose “mask of white … is almost ghoulish.” Donald Trump, who Akhtar calls the “racist real estate magnate embodying the rise of white property rights,” at least had the decency to spray himself orange. Readers might have expected Akhtar’s four years at Brown, which included many “an afternoon of prosodic analysis of ‘Leaves of Grass,’” to have accustomed him to America’s pallid visage.

He characterizes American culture as little more than “racism and money worship.” Christianity reduces to “an aggrandized misinterpretation founded on an ontological absurdity.” An American-born Muslim character in one of his plays confesses to a “sense of pride” on 9/11.

Yet poor Mr. Akhtar suffered “tense looks … double takes … shit people say under their breath” in the nerve wracking days after September 11. Thousands of Americans who lost spouses, parents, children, friends, neighbors, and colleagues would happily put up with a lifetime of such petty rudeness for just one more hug with their murdered loved ones. Politically, Homeland Elegies forces readers to consider how the neocons’ conception of America as a creed holds up against one character who complains “the longer we stay, the more we forget who we are” while another rejoices “I’m glad to be home” after returning to Pakistan. Pace Twain’s borrowed theory, Akhtar’s work inadvertently juxtaposes diversity’s fiction with culture-clashing truth.

(John Greenville)

The Forgotten Slave Trade: The White European Slaves of Islam, by Simon Webb (Pen and Sword History; 208 pp., $39.95).

In America, public discussion about slavery—when it doesn’t devolve into BLM activists burning cities or congressmen bending the knee—is premised on important but erroneous assumptions: only blacks have been enslaved; black slavery was racially motivated; discussion of the Atlantic slave trade as part of the larger history of human slavery minimizes white enslavement of blacks and is therefore racist; slavery under Islam—past and present—never happened. Simon Webb’s book is the latest addition to the growing number of books that expose the lie uniting these assumptions.

Webb’s book is not the best on the subject or the most comprehensive. One should rather turn to Giles Milton’s page-turning White Gold or Robert C. Davis’s scholarly Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800. But he nevertheless gives the general reader a solid introduction and useful survey of slaving activity by the Muslims of North Africa over the course of several centuries. And, while Milton focuses on Morocco (an independent realm) and Davis is primarily concerned with the effect of the slave trade on Italy, Webb broadly covers all of the North African states (Tunis, Tripoli, and Algiers were under Ottoman rule).

The Islamic slave trade extended far beyond North Africa—its eastern hub was Zanzibar—and easily dwarfed the import of slaves to America. In the early years of the trade, men were used as galley slaves on Muslim ships while women were sold into sexual slavery. Muslim masters also devised various means of torture as punishment. The beating of a person’s feet with a bastinado was a favored method and makes an appearance in Don Quixote (Cervantes himself was imprisoned in Algiers for five years). Here, Webb could have made greater use of white slave narratives to describe conditions of captivity.

Overall, though, he succeeds in placing Barbary slavers in the larger context of Islamic enslavement of white European Christians during the reign of the Ottomans. This includes the systemic enslavement of Balkan children (the Devshirme), the bulk of whom were Slavs (the etymological origin of the word “slave”). According to Webb, this was not piracy. It was simply jihad waged by other means. And since many unredeemed captives converted to Islam, it is hard to disagree.

(Timothy D. Lusch)

Leave a Reply