It is by now a truism to say that the border between the United States and Mexico encompasses a third nation, one that shares in both societies but that forms its own culture. That may well be, but the border represents different things to different people. For some Anglos, it is a glimpse of Third World exoticism out the back door. For others, it is a safety hatch, an entrance into a land of mescal, sun, and the long goodbye. For some Mexicans, it stands as a hateful reminder of lost territory. For still others, it is an obstacle to be overcome in reaching the land of milk and honey. For writer William Langewiesche, however, the border represents a great rift, a chasm separating two inimical nations that alternately despise and ignore each other: in his view, it stands as the most visible symbol of political division in the present world. “Only here,” he writes, “do the first and third worlds meet face-to-face, with no second world in between.”

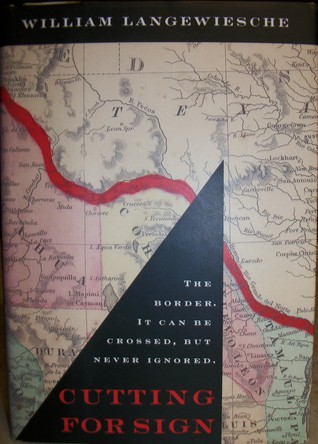

In Cutting for Sign, his first book, Langewiesche recounts a composite journey along the frontier, observing and reporting what he sees along the way. That journey has been made many times before, most recently by writers Tom Miller (On the Border) and Alan Weisman (La Frontera), but Langewiesche finds new twists that keep his book from treading on theirs, particularly in his attention to political issues. He starts off literally in medias res, viewing the broad sweep of the border from the midway vantage point of the Big Bend. From there, he reflects on his dealings with a hard-edged Mexican ranch hand who once lived near his place outside of Marfa, Texas, a man with whom he could never quite connect. Langewiesche returns to him at several points in the book, most tellingly when describing their last encounter: “We had little to say,” he remembers, “and he wanted me gone.”

Cutting for Sign has its origins in a long article Langewiesche wrote two years ago at the commission of the Atlantic; in expanding it to book length, he has introduced much thoughtful reflection on matters he had earlier reported only briefly: immigration, cultural conflict, the economy of drug smuggling, local power struggles, clashes between Anglo- and Mexican-American interest groups, and so on. His on-the-ground reportage is solid work, and some of the best moments of the book come when he is among the people for whom the international line means life-and-death political reality. He gives us a view of the daily life of a Border Patrol agent in San Ysidro, California, where the frontier ends in ocean, a routine that involves the endless frustration of never being able to halt the tide of illegal entry from Mexico into the United States. (The agent sighs, resignedly, “We could link hands out here and still not stop them.”) Langewiesche uses the occasion to embark on an intricate discussion of current immigration policy, arriving at a provocative conclusion: given our current social and economic woes, the border needs to be sealed more tightly. “Impoverished immigrants,” he argues, “do not cause these problems, but they add to them.” His call for greater restrictions does not keep him from appreciating the good reasons the alambristas, the wire-jumpers, have for moving northward. Neither docs it ignore the agent’s unhappy observation: “The truth is that everyone who persists eventually manages to enter the United States.”

Langewiesche has a special interest in the border’s economics, legal and illegal. He takes us alongside a Tohono O’odham tracking party that works the old Devils Highway, “Cutting for Sign”—searching for tracks—of narcotraficantes, smugglers who use the sparsely populated reservation as an avenue for bringing cocaine and marijuana to gringo markets. The agent in charge, like the border patrolman, recognizes that their work is largely futile, noting in disgust that advancements like barrage balloons and computers have made his work harder, not easier, by bringing a mountain of undigested information to his desk and thus keeping him from the field. When informed that he is about to be assigned a long-promised “intelligence analyst,” the chief says drily, “What the hell’s he gonna tell me—that marijuana’s green?”

Langewiesche also leads his readers inside what appears to be a rarity: an equitably run maquiladora, or American-owned factory in Mexico, where labor costs are low and environmental and business regulations are looser than north of the fence. He finds little to celebrate in having dug out the rare instance of an operation whose employees receive full benefits, sick leave, and free meals during the workday. In Langewiesche’s view, it will remain rare: “To the extent that Mexico ties its future to the United States,” he writes, “industry will continue to concentrate On the Border. The maquilas will shed their skins but live on in similar forms.”

Neither does he foresee much hope for improved relations between the United States and Mexico. “The ideal of a shared humanity,” he rightly observes, “does not withstand the mapmaker’s pen.” Despite the promises of the newly approved North American Free Trade Agreement, whose champions foresee a prosperous future for the continent’s inhabitants, Langewiesche believes that the status quo will prevail. The frontier will continue to be many things to many people, but it will always be a gaping chasm between two nations. As he says, “The Rio Grande”—and by extension the rest of the border—”has become boundary first and river second. And time is on the side of the government.”

[Cutting for Sign, by William Langewiesche (New York: Pantheon) 247 pp., $23.00]

Leave a Reply