The wavering course of United States foreign policy and our fumbling initiatives in the world’s trouble spots have turned a brighter spotlight upon governmental decision-making in this vital area. Our performances in Iran, Lebanon, and Nicaragua have raised questions about the capacity of our open government to deal with these recurring problems. And neither our relative success in Grenada (Notre Dame vs. the Little Sisters of the Poor) nor the Russian embroilment in Afghanistan has lessened concern about our method of developing and carrying out our national strategies.

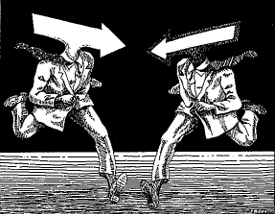

Looking back over our recent past, the authors of Our Own Worst Enemy have concluded that “for two decades now, not only our government but our whole society has been undergoing a systemic breakdown when attempting to fashion a coherent and consistent approach to the world.” As a result, our power to influence events has declined and we are “taken less seriously (by our friends as well as our adversaries) than at any time since World War II.”

This “unmaking of American foreign policy” became critical during the Vietnam War and the “opening up of American society and institutions in the sixties and seventies.” Presidents, it is asserted, have increasingly played domestic politics with foreign policy decisions. The Congress has disregarded its traditional jurisdiction, broadened its participation in delicate policy matters, and heightened its irresponsibility. A new “Professional Elite” of experts has succeeded the Eastern, consensus-oriented “Establishment.” Led by National Security Assistants, the White House force (aptly dubbed “Courtiers”) has grown in strength and has feuded with the “Barons” of Foggy Bottom with mounting success.

The authors have properly noted the effect of the general cultural revolution of recent years. Even such a hitherto stable institution as the Roman Catholic Church is now divided into orthodox, conservative, and reform wings. Deregulation has thrown business into turmoil; sexual mores and racial relations have been radically altered. It is not surprising that governmental practices should be unsettled. The question is how to get back to stability.

Presidents Eisenhower and Truman left foreign policy problems pretty much to Secretaries Dulles and Acheson, but their successors abandoned this judicious position. Kennedy became impatient at the cautious pace of career diplomats and started the trend toward activist, White House control, sending his merry men roving through the State Department until Dean Rusk cried out in anguish. Kennedy’s assessment of State was: “They’re not queer, but, well, they’re something like Adlai.”

Succeeding Presidents sought even more control. Nixon and Carter elevated Kissinger and Brzezinski to official equality and practical superiority over Secretaries Rogers and Vance. This led to bureaucratic bloodletting, fuzzy lines of command, and doubt as to who spoke for the Chief. Destler, Gelb, and Lake are on solid ground when they support the primacy of the Secretary of State. They argue that the National Security Assistant must keep his activities and advice private and ” not grandstand for the benefit of the media.

Neither Congress nor the media have clone much to contribute to a sensible foreign policy. Legislators have gotten involved in details of policy execution and exploited issues rather than clarifying them. The media have become “infused with the adversary culture” and amplified the exaggerations made in Congress. This is a harsh judgment, but largely justified. Certainly, Capitol Hill has been eagerly inclined to follow domestic special pleaders in such cases as Israeli expansionism and Turkish aid. But on the other hand, Congress has performed creditably in focusing on the tragedy of Vietnam and the stupidity of mining harbors in Nicaragua. In the final analysis, too, on Grenada, Lebanon, intelligence matters, and (previously) in Vietnam, Congress has been remarkably cautious in acting counter to the President.

Perhaps inevitably, when it comes down to brass tacks, the authors’ specific recommendations lack bite or sanction. Ideology and polarization, they say, should be reduced and partisanship cut back. Congressional staffs should be reduced and depoliticized. All true, but how are these reforms to be realized? Their hopes for the future lie in the mass of educated, nonpolitical citizens who inhabit the center of the political stage but are disorganized. Presidents, they hope, will see self-interest in statesmanship. Is it significant, one wonders, that Adlai Stevenson, whom they quote as an advocate of mobilizing thinking citizens by “talking sense to the American people,” lost two Presidential elections?

Two hopeful signs have appeared on the horizon. First, Secretary Shultz achieved control over a very diverse delegation, including Robert Mcfarlane and Richard Perle, at the Geneva talks. This could be the beginning of happier relations between Barons and Courtiers. Second, there is a rising tide of opinion which postulates the need for a return to party responsibility and reliable and acknowledged leadership in the Congress—a development devoutly to be wished for and one which could bring back sound policymaking and supportable policies.

Arms Control: Myth Versus Reality is a collection of discussions by 22 of the 60 participants who took part in a symposium on this critical subject at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace in 1983. The myth is that real arms control is feasible. The reality is that we are not faring well in our competition with the Russians in armaments and military strength and possible agreements would probably redound to the benefit of our opponents, especially without foolproof verification and monitoring.

The views of the contributors range from hostility to any discussions to resigned acceptance. They are agreed that the United States should reenter the field of strategic defense and should fund the development of defense technology as well as offensive weapons. This, of course, puts them squarely in support of President Reagan’s “Star Wars” proposal and in opposition to the main concern of Gromyko and his brethren who seek to limit adventures in outer space. If one could assume the existence of an invulnerable umbrella, there would be logic in resorting to such a mechanism; but given its expense, its intangibility, and its opening up of a new level of escalation, it is doubtful that it will provide a serious initiative except as a bargaining chip. In fact, the Hoover group’s proposals provide a potent brief for the Administration’s claims.

Some of the commentators question the fidelity of the U.S.S.R. in adhering to treaties already entered into and the reliability of their performance of any new agreements and, while it is inconceivable that the Kremlin would not test the very limit of permitted legality, at least some blame for conflicting interpretations of the ABM treaty, for example, must be laid to the ambiguity of the document. The more hard-line experts scorn the entry into any agreement while the less obdurate, emphasizing that such negotiations may be “cosmetic” rather than substantial, recognize their necessity but with the strictest provisions for inspection of compliance. The latter might well approve Lyndon Johnson’s prescription for dealing with the Russians. ”I approach them,” he said, ‘with my hand out but my guard up.”

Whether or not one can accept its proposals in their entirety, this collection edited by Richard F. Staar performs a signal service in providing cautionary material to moderate the expectations of the public both at home and abroad. With the differences of traditions and objectives between the contending parties, results will not be immediate and will be necessarily modest. The point to be made now is that the Russians have determined that it is in their national interest to cut the costs of their adventurism and the new talks provide an opportunity which cannot be disregarded. In the triple division of negotiations, some areas appear promising. Nevertheless, the technicalities, prejudices, and conflicting elements must be understood and it is to this understanding that the Hoover commentators have made such a substantial and arresting contribution.

Leave a Reply