Is there a distinctly British brand of heroism? That is the implicit question running through Christopher Sandford’s Zeebrugge, a gripping new history of the British naval raid in April 1918 on the German-held Belgian port of that name. The sheer audacity of the operation and its attendant tales of sacrifice and derring-do resulted in a resounding p.r. victory (if nothing else) that bolstered England’s resolve during the closing stretch of World War I. Judging from the multitude of eyewitness accounts Sandford presents, it would appear that the tone of exaggerated nonchalance that permeates British action entertainments to this day—think of James Bond smartly snapping his cufflinks amidst the latest swirl of carnage and mayhem—has some precedent in actual events.

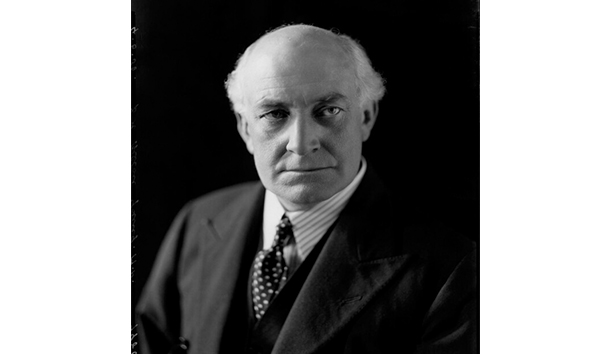

A swashbuckling spirit certainly animated the raid’s planning. As developed by Admiral Roger Keyes (Commander-in-Chief, Dover)—a colorful, hard-charging type in the Horatio Nelson mold—the proposed course of action involved a diversionary attack on the Zeebrugge “Mole,” or breakwater, by an aging cruiser flanked by two repurposed Mersey ferries; the ramming of a viaduct by two obsolete, explosives-filled submarines; and the sinking of three cement-laden “blockships” at the entrance to the harbor, theoretically blocking further German submarine incursions. All this was to be carried out in unpredictable weather without the benefit of modern navigational or communications technologies. Just a few months before, the Navy had managed to lose two submarines and 104 men en route to a training exercise (an incident that came to be known as the “Battle of May Island,” detailed in the opening chapter of Zeebrugge) precisely because of such deficiencies, so the Zeebrugge plan ought not to have inspired confidence in sober minds. In the final event, any skeptics were largely proved right, but that hardly matters in the creation of legends. “There are surely few sights and sounds more British,” Sandford asserts, “than a flawed master plan being rescued by the spirit of improvisation and personal fortitude of its individual participants.” “Rescued” may be an overcharitable assessment, but in terms of heroism this was indeed a spectacular turn for the fighting men of Great Britain.

In his retelling, Sandford eschews analysis of the causes and consequences of World War I, keeping his focus on the events and attendant personalities of the raid. An experienced biographer and erstwhile novelist, Sandford skillfully ratchets up the narrative tension as he moves toward the final onslaught. Unquestionably, the most powerful passages come straight from the mouths of the raid’s participants.

Every gun in the ship that could bear now gave tongue and the night was made hideous by the nerve-wracking shatter of the pom-poms, the deep bell-like boom of the howitzers and trench mortars, and all-pervading rattle of musketry and machine-gun fire,

recalled Able Seaman Wilfred Wainwright of the initial engagement with German shore defenses. “It was hell with a vengeance.” This sort of unforced lyricism competes with what Sandford terms “master classes in British understatement,” perhaps best exemplified by Lt. Commander Geoffrey Drummond, who, in the thick of battle, was heard coolly to remark to his subordinate, “I should get us away now, Number Two, as we’re in rather a warm spot here.” (Sandford concedes that quite a few “hearty oaths” were also uttered during the melee. They are not reproduced in the book.)

The cumulative effect of these, commingled with Sandford’s brisk, often graphic narrative, is an immersive quality one might normally associate with fiction. (Shelby Foote’s Shiloh and Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels spring to this reader’s mind.) Yet every poetic turn of phrase is underpinned by copious research. Among the numerous materials at his disposal, Sandford relied on the firsthand accounts of two of his ancestors: Lieutenant Richard Sandford, VC, and Lieutenant-Commander Francis Sandford, both heroes of the Zeebrugge attack. Of Richard, the pilot of one of the explosives-laden submarines that rammed the viaduct (the only part of the plan to go correctly), much could be made of his “arc”—his fall from grace during Operation EC1 (the aforementioned “Battle of May Island”) when the submarine on which he served, K6, holed her sister ship K4, sinking the latter boat with all her crew; his spectacular redemption at Zeebrugge just months later; and his untimely death from typhoid fever mere days after the signing of the Armistice. I say much could be made because the author chooses not to play amateur psychologist, instead presenting the facts and allowing his readers to draw their own conclusions. The approach is as effective as it is refreshing.

Similarly, the question of a uniquely British heroism, though touched on, is left largely to the reader to ponder. Richard Sandford stands as a solid example of the archetype his descendant highlights in his book: an improbable mix of stoicism and jocular humor on one side; wild improvisation, guile, and (it must be said) unnecessary risk on the other. Much has been made of World War I as the line of demarcation between the old romantic notions of warfare and the brutal modern reality of technologically enabled mass destruction, and it’s not as though the British didn’t get the memo on the new rules of the game—they were, after all, key players on the winning side. Yet, clearly, some of the old romantic traditions persisted, a few of which crossed the line from charming eccentricity into tactical folly. Consider Frank Brock, engineer of the artificial fog that cloaked the British ships’ arrival at Zeebrugge, a man who, had he survived, “would have attained to the highest power and eminence in his field” according to the Times. This “true English gentleman,” described by a colleague as someone who “acted at all times with the utmost decorum and restraint until the moment came to blow someone or something up,” was last seen running into the smoke on Zeebrugge Mole armed only with a revolver and his “box of tricks.” His body was never recovered. While it makes for a rousing exit, one can only speculate on what contributions this “all-round technical genius” might have made to his country’s efforts in the following war. And Brock’s pointless sacrifice was no anomaly; one of the reasons the storming of the Mole devolved into a chaotic and arguably futile affair was that so many officers got themselves mowed down during the initial charge. Even Admiral Keyes put himself unnecessarily in harm’s way, bringing his ship within range of the German coastal guns so he could better observe the events-in-progress. Sandford characterizes this generation of fighters as “generally more phlegmatic about the prospect of early death than we are today,” and in page after page he demonstrates both the positive and negative consequences of that attitude.

“Snatching victory from the jaws of defeat” is an oft-noted British talent—one that seems to extend to perceiving defeats as victories. As with the Dunkirk retreat in World War II, the Zeebrugge raid—a tactical failure in nearly every sense—quickly came to be viewed in the United Kingdom as a resounding triumph. Notwithstanding that the improperly sunk blockships set German submarine actions back by approximately one day, the general feeling was that a corner had been turned. And perhaps it had; while the German losses were negligible, the sudden appearance of HMS Vindictive, swathed in Brock’s artificial fog, bearing down on German soldiers stationed on the Mole may have inflicted a psychological blow that is difficult to measure. As one of those surprised soldiers remembered, “It was as if we had closed our eyes for an instant in a dark room and opened them again to see the devil himself standing before you.”

One question that remains unanswered at the close of the volume is whether the British man of action Sandford describes exists today. Without doubt, the type surfaced time and again during World War II and populated British Intelligence during the Cold War era. As noted earlier, this character has remained a staple of the popular imagination. But with the general devaluation of military heroism and the absence of large-scale conflicts engaging the U.K. at present, we cannot be fully certain that Sandford’s spirited account is not, in fact, an elegy as well.

“[I once] supped full of the horrors of life,” Zeebrugge veteran Lt. Edward Hilton Young wrote many years after the events of April 1918. “[But I have learned to] move ahead with something approximating joy in one’s soul.” Very few people would assert that Britain in the era of World War I was a better place and time to live in than our own. But it would be difficult to deny that it forged better men. Christopher Sandford’s fine contribution to battlefield literature is a testament to that fact.

[Zeebrugge: The Greatest Raid of All, by Christopher Sandford (Philadelphia, PA: Casemate Publishers) 272 pp., $32.95

Leave a Reply