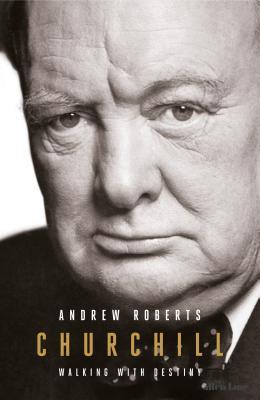

Of the making of books about Churchill there is no end. The latest is the best to date. Andrew Roberts reduces Churchill’s epic life to some 1,100 pages, offering a précis of the great events in which he was involved while drawing on 40 new sources. These include the private diaries of King George VI and the unpublished memoirs of major figures. Roberts has mastered the archives, and provides an enthralling, intimate picture of Churchill that reads as if it were a novel, with something piquant on every page as the author forges ahead at a level pace, never allowing the flow of the narrative to flag. We can sometimes forget that Churchill was a very funny man, and Roberts constantly finds room for the jokes with which Churchill enlivened his company at all levels, including Parliament, Roosevelt, and even Stalin. His domestic life, including his relations with his wife, Clementine, is fully treated. However, I shall confine myself to one aspect of Churchill’s legacy: war.

Churchill became, in A.J.P. Taylor’s term, a war lord. That does not mean that he was a warmonger, a charge often thrown at him. He had seen enough of war to know what it meant. He rode in the cavalry charge at Omdurman in 1898 under Sir Herbert Kitchener, and he served in the trenches in 1916. But he certainly revelled in war, once it was upon him, and he reckoned he knew a great deal about it.

He did. In 1911 he circulated to the Cabinet an eerily farsighted memorandum on the “Military aspects of the Continental Problem.” “I named the twentieth day of mobilization,” he wrote,

as the date by which the French armies will have been driven from the line of the Meuse and will be falling back on Paris and the South, and the fortieth day as that by which the Germans should be extended at full strain.

Both forecasts were almost literally verified by events. In August 1914 while Von Kluck’s army marched around the perimeter of the battlefield, following the overly ambitious Schlieffen Plan, the French, as Churchill predicted, fell back on Paris and brought up troops to decide the battle of the Marne. Churchill was a man fit to be in charge of a war, and not his leader, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, who spent wartime Cabinet meetings writing letters to his mistress.

The Dardanelles was the crisis for Churchill. He backed it, though he was never in charge of the major decisions, and has been reproached by historian after historian for the failure of the campaign. And yet in a letter to Asquith on December 29, 1914, he wrote: “Are there not other alternatives than sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders?” That is exactly what happened in the four grievous years that followed. The reasons became clearer during the Dardanelles campaign, and its two landings in Gallipoli. The first, in April 1915, was a complete botch-up. The Royal Navy even forgot about the importance of tides. The second, on August 7 at Suvla, was an initial success, with the Turks taken by surprise and the landing virtually unopposed. Incredibly, though, the British troops, then and on the following day, were allowed to frolic in the sea. A hard-driving general would have flogged the newly landed troops up the slopes to the ridge and beyond. For two days the army did nothing except consolidate, while the Turks, led by Mustapha Kemal, the man of destiny who became Kemal Atatürk, rushed up reinforcements and held the vital ridge. The demonic energy of Kemal was set against the British commander, General Stopford, an old fool appointed by Kitchener because the younger generals refused to take over in Gallipoli. They knew well that great careers for generals existed only in France. The very term chateau general was coming into being. As Roberts says, “The quality of the senior officers was generally abysmal because the Western Front was always the first priority.” The military establishment paid obeisance to the doctrine that decisive battles had to be fought in the major theater of the war, which meant that resources should not be diverted from France where the generals held sway. Stopford was relieved of his command on August 16, but the opportunities he had squandered never returned.

Clement Attlee had fought at Suvla and believed all his life that the Dardanelles campaign was “the only imaginative strategic idea of the war.” My father would have agreed. He spent four and a half months at Suvla, and often spoke to me of his experiences, which included being detailed for the suicide squad ordered to cover the nighttime evacuation of the beach. It passed off without a hitch, a superbly managed retreat. By then Churchill was finished. Asquith had sacked him. He was the scapegoat for the failures of the military leaders, Kitchener above all, who sent out an officer to report on evacuation from the peninsula. “General Monro was an officer of swift decision. He came, he saw, he capitulated.” I would add, “and obeyed orders.” The establishment then hung about Churchill’s neck a reputation for faulty and hasty judgment. It stayed with him right up to his becoming premier and war lord.

During the 1930’s Churchill was out of office. He fell out of favor by opposing the plans to give India dominion status, and he made the romantic error of supporting Edward VIII over his abdication. During the crisis British schoolboys sang gleefully, “Hark the herald angels sing, Mrs. Simpson stole our King.” But all this turned to Churchill’s advantage, for he held no responsibility at all for the government’s policy toward Hitler. He had criticized the leaders—first Stanley Baldwin, then Neville Chamberlain—for Britain’s military unpreparedness. In these matters he was exceptionally well informed, for numerous highly placed sources knew he was the man to contact. After Munich he pinned this judgment on Chamberlain: “we have sustained a defeat without a war,” a verdict widely accepted by posterity. But there was a case for the government: The military leaders, especially Dowding for the R.A.F., knew that they needed time to build up their forces. They supported the Munich agreement. Hitler was furious at Chamberlain for averting the war he wanted in 1938. There was, however, no case for Chamberlain’s guarantee to Poland in March 1939, an empty bluff which Hitler scornfully called. And so to war: On September 3, 1939, Churchill was recalled to the Admiralty, and the message went out to the Navy: “Winston is back.” The establishment still loathed him but could not refute his claims. In May 1940 he became Prime Minister. “I acquired the chief power in the State,” he wrote,

which henceforth I wielded in ever-growing measure for five years . . . at the end of which time, all our enemies having surrendered unconditionally or being about to do so, I was immediately dismissed by the British electorate from all further conduct of their affairs.

World War II took a totally different course in leadership and command. World War I was run by the military, which dominated the politicians. Churchill had no intention of repeating that folly. He took and maintained control of all operations, demanding that a single mind should prevail. This did not mean Führerprinzip. The war was rationally conducted: The Joint Chiefs of Staff made sure that Britain and the U.S. concerted their policies whatever their internal differences, and their story is well told by Roberts in his Masters and Commanders. Churchill never overruled Field Marshal Alan Brooke, but their arguments were fraught with disagreement and the outcomes were always intellectually justifiable. At the end of the war in Europe, Churchill called a general election which, to global amazement, he lost. The British people, who saw in Churchill the embodiment of the nation’s life force and supported him throughout the war, did not care for Conservative rule in peacetime. It is an odd fact that in the three general elections when the party was led by Churchill, he lost all of them on the popular vote. In 1951 the system was skewed towards the Conservatives, and Churchill got home on a parliamentary majority. He had withstood a Daily Mirror front-page headline on election day: “Whose Finger on the Trigger?” depicting a hand on a gun. The outrageous suggestion was that warmonger Churchill was likely to start a third world war. Churchill in fact dreamed of a peace conference, in which the West and the Soviets under Stalin would strike some kind of bargain, with Winston in the starring role. He used this fantasy to keep Anthony Eden waiting for the succession. Still, there is no doubt that the British people welcomed the return of their national hero and were comforted by his presence at the head of their affairs.

Churchill’s legacy rests on the great cantilever of his writings. These were recognized by the Nobel Prize in Literature (1953) and are a constant joy. For those not fully launched into the sea of his writing, I would suggest the mellow My Early Life (1930), his best-selling single-volume book, and The World Crisis, 1911-1914 (1923), especially the early chapters on the run-up to the Great War. Balfour said it was “Winston’s brilliant autobiography, disguised as a history of the universe.” Marlborough (1933-38) comes in four volumes, but the treatment of the Blenheim campaign can be read alone for its astounding narrative. The “scarlet caterpillar” of Marlborough’s forces crawled across Europe, while the French had to wait for him to declare his intentions at Koblenz. Here, at the Deut sches Eck, with the choice between a Rhine and a Mosel campaign, he kept on along the Rhine to the Danube and the storming of the Schellenberg. Churchill’s wide knowledge of world leaders comes out in Great Contemporaries (1937), an engrossing set of memoirs. Readers may be surprised at his assessment of Hitler in 1935. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (1956-58) has a classic distillation of the American Civil War, “which must upon the whole be considered the noblest and least avoidable of all the great mass-conflicts of which till then there was record.”

My vote for a most striking testimony to Churchill’s enduring fame goes to a painter, Sir James Guthrie, for his group portrait Statesmen of World War I (finished shortly before his death in 1930), which you can see at London’s National Portrait Gallery. The setting is imaginary, a vast hall flanked by Doric columns in the shade of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It is an allegory of imperial victory. The forefront depicts a Cabinet meeting, with Balfour on his feet, orating. But the eye is drawn to the central figure, who alone in the group fixes the viewer with an intent, direct gaze. A Rembrandtesque shaft of sunlight comes from the shadows and falls like a spotlight on the face of Churchill. Each statesman was painted in the pose he would adopt in the finished group. As clearly as the painter can, Guthrie is saying “ecce homo.” Posterity does not dispute his judgment.

[Churchill: Walking With Destiny, by Andrew Roberts (New York: Penguin) 1,152 pp., $40.00]

Leave a Reply