As we all know, during the Civil War, an expansive, democratic, progressive, multiethnic North defeated a bigoted and reactionary South, so that government of the people, by the people, and for the people should not perish from the earth. Like so many commonly held beliefs about the war (which are now being enforced as official, indisputable truths), the picture is jaundiced. (In this respect, rather, it is like many other official untruths: For example, that the war was fought for the benefit of the slaves, that Andersonville was worse than Northern prisons, or that Confederates were vicious barbarians who made war on women.)

Most know about Meagher’s Union Irish brigade and its heroic charge at Fredericksburg. Kelly O’Grady sheds some interesting light on a familiar story: Gen. Meagher never exposed himself to fire; while, so far from being an exhibition of Irish-American adherence to the Union cause, the Fredericksburg debacle caused a great decline in Irish support for the war. And Meagher was not much of an Irish patriot—unlike John Mitchel, a true Irish nadonalist, who served the Confederacy and gave it the lives of two sons. Pope Pius IX, at the instigation of the heroic Confederate priest John O’Bannon, strongly condemned and curbed Union recruiting. As a Dublin newspaper observed in 1861, “We cannot but recollect that in the South our countrymen were safe from insult and persecution, while ‘Nativeism’ and “Knownothingism’ assailed them in the North.”

In fact, the Northern cause was big on WASP supremacy. The North had a strong Cromwellian streak, which caused it to decry Catholicism and non-WASPS in general. (German Protestants were okay.) And this sentiment was strongest in Northerners who tended toward abolitionism and harsh anti-Southern attitudes. One of the reasons many people disliked Southerners, as evidenced by the sources of the time, was that they were considered not WASP enough. More people disliked slaveholders because of their close association with Africans, not because the evils of slavery. In fact, the most fundamental goal of the war (and of Reconstruction) was to keep blacks out of the North.

This aspect of Northern society is illuminated in Fire and Roses. Nancy Schultz shows how economic and religious tensions were projected onto Catholic newcomers—leading to the spread of malicious rumors, the sacking and burning of a convent, and the refusal of local audiority to punish the perpetrators. (Such things went on in Philadelphia as well as Boston.) Indeed, the destruction of the convent reminds me—in all sorts of ways—of Sherman’s progress. Catholic churches and convents in the South went up in flames as readily as any other religious buildings. Probably, Mary Surratt would not have been executed if she had not been a loathsome papist.

All of this occurred while Catholics and Jews were being honored and elected to office in the South by Protestant neighbors. Bishop John England of Charleston was the leading prelate in America, on friendly terms with all the clergy of the community and invited to address the legislature. There were two Jewish and several Catholic senators elected from Southern states before the war, something nearly unthinkable at that time in the North.

All immigrants from whatever quarter (including the North) who had resided in the South for any length of time before the war were regarded there for what they were: loyal Confederates. In fact, the antebellum South, far from being narrow and bigoted (whatever may be said about later times), had a tremendous power to bind the allegiance of diverse elements.

It will surprise many—though it should not, since the truth has always been there for all to see—to learn that the South held the allegiance of its Jewish citizens, who fought and sacrificed as loyalty as any other group. Later Jewish immigrants who knew nothing of the war adopted the Union viewpoint in order to be “good” Americans. And so the story of Jews in the South—who probably represented a greater percentage of the population than in the North—has not been told until now. Robert Rosen, a Charleston attorney and amateur historian, has given us a valuable work that brings to light the lives of a forgotten (though interesting and worthy) group of Americans. (I mean “amateur” in the best possible sense of the word, since amateurs are the writers who are able to see things that conformist academics never consider and, therefore, currently compose, and will continue to compose, our real historical works.)

Jewish Southerners perceived (rightly) that New England abolitionists were also strongly antisemitic. Abolitionist Theodore Parker believed Jews to be “lecherous” people who sometimes really did kill Christian babies. William Lloyd Garrison described a New York newspaper editor as “a miscreant Jew,” “the enemy of Christ and liberty,” and a descendant of “the monsters who nailed Jesus to the cross.” The catalog of such sentiments among the most fervent abolitionists and supporters of the Union war effort is large, and it is headed by John Quincy Adams.

Americans’ historical understanding today is in a peculiar state. While honest, sincere historians are always bringing to light new and interesting nuances to the central events of our history, their discoveries make no headway with the academic establishment (and the political forces claiming historical justification) and never even slightly affect the accepted understandings that, for academics as well as politicos, are increasingly becoming groupthink slogans—indifferent not only to nuance but to all evidence and argument. Still, many fine, neglected works shed new light on antebellum and wartime America and its diverse peoples. The next great subject that needs definitive and exhaustive treatment is the story of the tens of thousands of black men who were part of the Confederate armies. Hundreds—probably thousands—went with Lee’s army to Pennsylvania—and took their wounded or dead masters back home. In fact, the Southern soldiers who survived the famous attack at Gettysburg—I am told by a close student of the subject—returned to Confederate lines marked by a multitude of black faces.

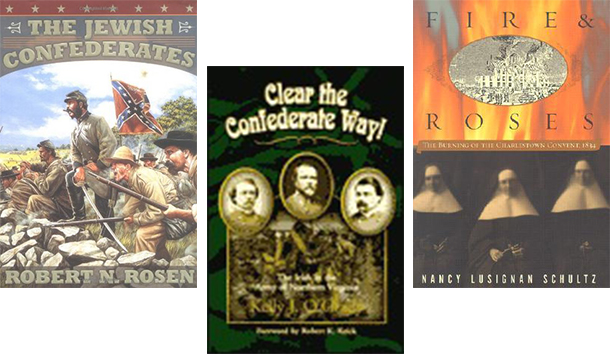

[The Jewish Confederates, by Robert N. Rosen (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press) 517 pp., $39.95]

[Clear the Confederate Way: The Irish in the Army of Northern Virginia, by Kelly J. O’Grady (Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing Co.) 348 pp., $26.95]

[Fire and Roses: The Burning of the Charleston Convent, 1834, by Nancy Lusignan (Schultz New York: Free Press) 317 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply