“Less is more” has proved to be (more often than less) a dreadful aesthetic credo, inspiring and justifying boldly insipid architecture better suited to robots than to humans, monotonous music in which the intervals of silence are the most welcome parts, minimalist visual art that is an insult to the visible universe, and poems little different from workaday utterance one would be generous to call prose. But the clause “less would be more” makes a lot of sense: a great deal less poetry than we have would probably be a good thing. Never has more poetry been published; never has it mattered less.

There are profound sociological reasons for the superabundance. Dana Gioia focuses on one: the proliferation of “creative writing” courses, which require instructors who must in turn be validated by publication. “Like subsidized farming that grows food no one wants, a poetry industry has been created to serve the interests of the producers and not the consumers.” That is not quite exact, since the consumers mostly are the producers —one of Gioia’s points, in fact. Which is why contemporary poetry matters so little. “American poetry now belongs to a subculture,” he writes, and not to the “mainstream of artistic and intellectual life.”

There is a lesson here I do not think most poets will learn. The generally educated person who in another time kept up to some degree with the poetry of his day, because not to do so was not to be generally educated, no longer feels so compelled—in spite of the compliment the poet pays him of speaking just as he does. Perhaps I should say “because of” rather than “in spite of”; if poetry is not a “rite,” as W.H. Auden said, “deliberately and ostentatiously different from talk,” then why bother with it? Would you attend the ballet to see dancers merely walk about the stage? But probably most “poets” could not benefit from the lesson if they learned it. We have far too much “poetry” because we have far too many unworthy claimants to the poet’s mantle.

The last essay of Gioia’s book, “The Poet in an Age of Prose,” since it is a discussion of the “New Formalism,” might be considered an answer to the first and title essay, “Can Poetry Matter?” The new formalists consciously seek a general audience who “innocent of theory . . . had somehow failed to appreciate that rhyme and meter, genre and narrative were elitist modes of discourse designed to subjugate their individuality.” But in another essay, “Notes on the New Formalism,” Gioia makes some observations that temper one’s optimism. Much of the new formalism is “pseudo-formal.” The poem looks formal by virtue of its visual arrangement on the page, but the “architectural design has no structural function” as the “words jump between incompatible rhythmic systems from line to line.” The reader’s experience is “rather like hearing a conservatory-trained pianist rapturously play the notes of a Chopin waltz in 2/4 time.”

But who is this Gioia? By what authority does he judge? He is the author of Daily Horoscope (1986) and The Gods of Winter (1991), whose poems are what poems have traditionally been but seldom are now: “the fine / disturbance of ordered things when suddenly / the rhythms of your expectation break / and in a moment’s pause another world / reveals itself behind the ordinary.” And in the instance at hand he is the author of the most lucid examination of poetry I have read since Babette Deutsch’s Poetry In Our Time (1954)—which in my scale of values is like favorably comparing a book of historical reflections with those of John Lukacs or of philosophical speculations with those of Hannah Arendt.

In a review I must sight some of Gioia’s other general concerns; “the dilemma of the long poem,” regional poetry, poetry’s silence on business even when the poet is a businessman. But Gioia’s concerns are not merely general and theoretical. There is excellent practical criticism of old masters like Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot, Robinson Jeffers, and lesser voices, and his essays on Weldon Kees, Robert Bly, Howard Moss, and Donald Justice are the most perceptive on those poets you will find anywhere. Mercifully, neither Maya Angelou nor Rita Dove (inaugural embarrassment and new laureate, respectively) are discussed, but 17 other poets receive Gioia’s undivided attention. A few might wish that were not the case.

While Gioia can be exceptionally generous—John Ashbery “is a marvelous minor poet, but an uncomfortable major one” (yes, that’s generous)—he can also be wicked; “Ideas in Ashbery are like the melodies in some jazz improvisation where the musicians have left out the original tune to avoid paying royalties.” Commenting on one of Bly’s brutalizations of Mallarme, Gioia judges, “Not only does it not seem like the verse of an accomplished poet, it doesn’t even sound like the language of a native speaker.” Bly’s translations are important because they “underscore his central failings as a poet. He is simplistic, monotonous, insensitive to sound.” “One can always tell when Bly is excited. He adds an exclamation point.” There are lofty emotions here, but Bly lacks the skill to make his reader feel them, so “the reader remains outside the emotional action of the poem, a little embarrassed by it all, like a person sharing a train compartment with a couple whispering romantically in baby talk.”

I single out Bly for two related reasons. First, I delight to see an extremely influential poseur receive the critique he so justly deserves. (On reconsideration, I’m sorry Angelou was left out.) Second, I want to suggest that Gioia practices what he preaches. One of his major complaints about the poetry subculture, one of the reasons it is so hard to take seriously, is that its members practice too much backscratching instead of honest reviewing, while they ought to regain potential readers’ trust with candid criticism; “Professional courtesy has no place in literary journalism.”

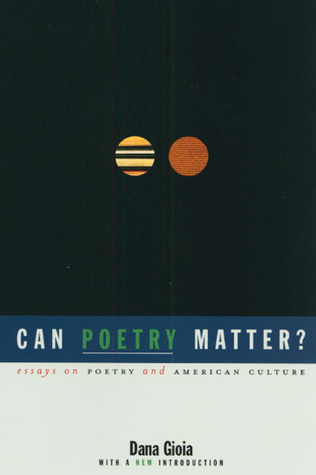

[Can Poetry Matter? Essays on Poetry and American Culture, by Dana Gioia (Saint Paul: Graywolf Press) 257 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply