The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working- Class Revolution; By David Paul Kuhn; Oxford University Press; Hardcover, 416 pp., $29.95

Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest; By Lawrence Roberts; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; Hardcover, 448 pp., $28.00

When rioters pushed past the Capitol Police and stormed the U.S. Senate, they disrupted a legitimate legislative proceeding and attempted to impair the function of government. Also intent on disruption were those who forcibly entered a dozen congressional offices.

But this was not Jan. 6, 2021. And these were not Trump supporters.

It was late April 1971 and the rioters were in town for the upcoming Mayday protests. Fifty years before the QAnon Shaman waved the American flag from the Senate podium, anti-war activists donned military uniforms and chased burlap-clad women through the halls of Congress. The women—acting out the parts of Vietnamese mothers—spewed fake blood and screamed “God have mercy!” and “Don’t kill my baby!” Only weeks before, the Weather Underground had detonated a bomb in the Capitol.

These incidents are rarely mentioned in our day. They don’t fit the narrative. It is how the Capitol Riot of 2021 can be uniformly described by CNN, ABC, and President Joe Biden as “unprecedented.”

But this is not to give equal weight to disparate historical events. Nor is it to engage in political scorekeeping.

It is, rather, to highlight what I view as a destructive impulse on both right and left; a rage symptomatic of the failure of politics to contain our cultural division. It exists not at the extremes of free speech but in the dark heart of people for whom politics has become inadequate. “Rage and frenzy,” Edmund Burke wrote, “will pull down more in half an hour than prudence, deliberation, and foresight can build up in an hundred years.”

Two recent books consider rage-filled episodes in 1970 and 1971. David Paul Kuhn’s The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution chronicles the political and cultural tremors caused by New York City construction workers and tradesmen who marched and rioted in Lower Manhattan in May 1970. This marked the beginning of a movement to the right for blue-collar whites, culminating of course in the Trumpian earthquake of 2016.

Lawrence Roberts’ Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest tells the story of the Mayday Tribe’s massive antiwar protests in Washington, D.C. over the course of a week, in the hopes of forcing the Nixon administration to end the war in Vietnam. This marked the last hurrah of the antiwar movement.

The year between these two surface events marks a fault line between opposing forces, a divergent boundary in the cultural tectonics of our country. Over the last 50 years it has widened into a rift between irreconcilable visions of America. Demands differ and demographics change but the friction is permanent and leaves few places in our personal and public lives undisturbed.

Yet friction is contact, and that would off er some hope. But, amid the eruptions and aftershocks of political violence, we talk to each other less and past each other more. The phenomenon of cultural divergence discourages inquiry into how we might come together, leaving many to question when the whole thing will come apart.

During the heady days of early 1970, it almost did. “If you didn’t experience it back then you would have no idea how close we were, as a country, to revolution,” one White House aide said. President Nixon’s announcement of the Cambodian campaign sparked a new wave of anti-war protests. On May 4, four students were killed and nine wounded when National Guardsmen opened fire at Kent State. Three days later in New York City, as the funeral procession for one of the students wound its way Uptown, anti-war protestors gathered in Lower Manhattan. Near Federal Hall, protestors skirmished with a couple dozen construction workers who took ofpages fense at what they considered anti-American behavior. At the site of the old Singer Building, where the new U.S. Steel building was being built, hard hats chucked food, cans, and other items down on the protestors. Worse was still to come.

David Paul Kuhn tells the story in marvelous detail. He has a reporter’s eye and a novelist’s pen. From the first bottle thrown to the last punch, Kuhn’s narrative makes for gripping reading. The middle chapters are especially dizzying as he manages to capture something of the chaos and confusion on the streets. But he never loses sight of the broader story which, coupled with the street action, carries the air of tragic inevitability. “The hippies’ and hardhats’ outlooks were, by now, almost inconceivable to each other,” Kuhn writes. “Yet circumstance had compressed that cultural and class divide into the narrow landmass of Lower Manhattan.”

The hard hats were angered by what Pat Buchanan called the “revolt of the overprivileged” (not unlike the catastrophizing “snowflakes” marching for social justice today). Kuhn amasses evidence demonstrating the flagging fortunes of the white working class, its overrepresentation in fighting the war in Vietnam, and its outmoded values. Hard work, duty, service to one’s country—these were the values under attack by the anti-war left.

Many hard hats—veterans of WWII, Korea, and Vietnam—were not pro-war, but they opposed the blatant anti-Americanism of the anti-war movement. What’s more, they saw through the grating hypocrisy of what Kuhn calls the “New Left’s tendency to get high-handed about American imperialism while not only remaining silent on the terrors of communism but also waving those red flags.” Students waving the Vietcong flag while desecrating our own was too much for the hard hats to bear.

Violence exploded the next day, known ever after as “Bloody Friday.” At Wall and Broad Streets hundreds of construction workers countermarched and confronted the student protestors.

Chaos ensued. Students chanted, taunted the hard hats, and some threw bottles. The construction workers chased them down and beat them to a pulp with fists, wrenches, and pipes. The police, with some exceptions, largely stood by. Thousands of spectators jammed the streets, some merely to watch, others in support of the hard hats. In a bizarre sequence, Kuhn describes the snow globe effect of ticker tape and confetti—reserved for such triumphs as the Apollo lunar landing—which fell upon the hard hats from hundreds of offices above. Local businessmen, investment bankers, and even a thousand clerical workers joined the hard hats’ parade through Lower Manhattan.

The crowds eventually moved toward Pace University and City Hall, where the clashes continued. Some anti-war protestors were armed with machetes, metal bars, and knives. Others threw bricks at the workers from atop university buildings. The hard hats went about the business of beating up protestors, many of whom were no match for the burly blue-collars.

By the end of the day, back in Lower Manhattan, the action petered out. But over the next couple weeks, in New York and across the country, hard hats and their supporters held marches and rallies. One rally in New York City—dubbed “Workers’ Woodstock”—saw 150,000 people turn out for the hard hats. Included in the throng—inconveniently for the left—was a contingent of Mohawk Indian ironworkers.

Some of the hard hats later regretted their involvement. Others were proud, not of their brutality but, as Kuhn writes, “what it inspired and the message it sent.” Long before it was in the business of canceling the “unwoke,” The New York Times unsurprisingly condemned the hard hats, but with a shocking equivalence. The workers, the paper said, joined “revolutionaries and bomb-throwers on the left in demonstrating that anarchy is fast becoming a mode of political expression.”

Anarchy was precisely what the Mayday Tribe was going for a year later on May 3, 1971. Organized by Rennie Davis, one of the Chicago Seven, Mayday was part of the “Spring Offensive”—a martial plan by loosely connected radical organizations—to reenergize the anti-war left with series of protests and demonstrations. The goal was to shut down Washington, D.C. “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government,” Davis declared.

Lawrence Roberts does an admirable job untangling the web of organizations involved in planning Mayday. His book is organized, thorough, and quite readable. It is not objective, however. It is a minor irritation to discover at the very end that Roberts was himself a participant in the Mayday protest and one of thousands arrested. This does not disqualify him of course but it does explain his use of loaded language throughout—White House communications were “disinformation,” protestors routinely referred to as “kids,” city lawyers were “battered” and suffered a “rout” from the protestors’ legal defenders. It also explains his morality-play characterization of Davis, Dave Dellinger, and a Rolodex of other radicals as virtuous, while the D.C. police, FBI, and Nixon administration play the villains.

The Mayday protests—and the smaller demonstrations that preceded them—were highly coordinated, the result of months of planning at the national and regional levels. They were also tensely negotiated. Organizations dedicated to peace bickered over things like money and speaking order. But through the mediation of Dellinger, also of Chicago Seven fame, the coalition of coalitions held together. The Nixon administration also gave the organizers a gift with the U.S. incursion into Laos during February and March. As the invasion of Cambodia had done a year before, the expansion of the war galvanized the anti-war left and all but guaranteed a massive turnout.

Davis and his fellow organizers— known as the Tribe—disseminated the Mayday Tactical Manual in advance of the protests to ensure that the planners’ directives were carried out. Roberts, regrettably, only references the manual and does not include it in an appendix. It was so thoroughly prepared even the Pentagon brass praised it. In what would today be called a blatant act of cultural appropriation, the manual’s cover was adorned with the feathered head of an Indian warrior, not unlike the logo of the team formerly known as the Washington Redskins. The manual clearly spelled out the Tribe’s radical motive: “Because of the racist nature of the Federal government, closing down the apparatus that controls the War against Indochina and America’s oppressed is a relatively easy operation if it is coordinated.”

America’s oppressed didn’t bother showing up. Roberts observes that “anyone standing on the platform could view a sea of white faces.” And despite the left’s lip service about equal rights for women, planning and decision-making were left to the men. It was a regular complaint in the anti-war movement that women were expected to cook, clean, and perform secretarial duties. Roberts singles out one male activist for being willing to do these menial tasks—anything to help the movement. But, it turns out, he was an informant for the D.C. police.

The Tribe secured a permit to gather the protestors in West Potomac Park. The Mayday Tribe renamed it Algonquin Peace City after native inhabitants of the area. Pungent scents of patchouli and pot wafted over the park as speakers harangued and bands played. Thousands more arrived by the hour. President Nixon—whose private remarks often mixed the profane with the profound—believed good weather aided turnout, saying, “All the jackasses were down here and screwing around.” He was, by his own admission, tired of all the “bearded weirdos.”

But by early Mayday morning, protestors fanned out across the city to block bridges and roads, denying government workers access to their workplaces. Nixon wanted the main roads and bridges kept open. To achieve this goal, D.C. Chief of Police Jerry Wilson suspended department rules to allow for mass arrests.

It is hard to see how Wilson could have done otherwise, but Roberts is unsympathetic. Both Wilson and Nixon come in for a good lashing as upwards of 12,000 people were ultimately and, according to Roberts, improperly detained. He spends many pages chronicling the poor treatment of arrestees, particularly the crummy sandwiches, overcrowded cells, and lack of blankets for those kept outside. “This is concentration camp stuff,” one of the protestors, the famous pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock, said following his arrest at the 14th Street Bridge.

Roberts makes much of the fact that Nixon’s involvement—unreported until now—was more intimate than previously known. Chief Wilson took responsibility for departmental lapses, while others claimed individual officers got caught up in the moment and were overzealous in arresting groups of people. Nixon’s directive aimed at keeping the government open was within his purview. He was proud of how he handled the massive attempt to shut down the government and said as much to others. This isn’t much of a revelation and Roberts’ attempt to surround it with an aura of scandal, akin to the Pentagon Papers or Watergate, falls flat.

Most of those arrested on Mayday were released the next evening. Those that were not had refused to be fingerprinted or to post a $10 bond. Roberts chose the latter and was released. Almost all of the cases were quickly dismissed and just under two dozen remained open by the end of the year. Roberts sees this as both a legal victory for the protestors and a condemnation of the justice system. But it is rather a testament to the American system of justice that the remedies provided by constitutional law worked. It is what separates us from China, Russia, and North Korea.

The recent BLM/Antifa riots on the left, and the Capitol riots on the right, I believe are the latest eruptions at the divergent boundary of American culture. Rage is all that fills the rift now. It is, at the deepest level, a spiritual problem. In that sense, political solutions are always inadequate. But our political institutions, however flawed, are mediating institutions. Their deliberative possibilities offer hope, even if Americans seem to have lost it.

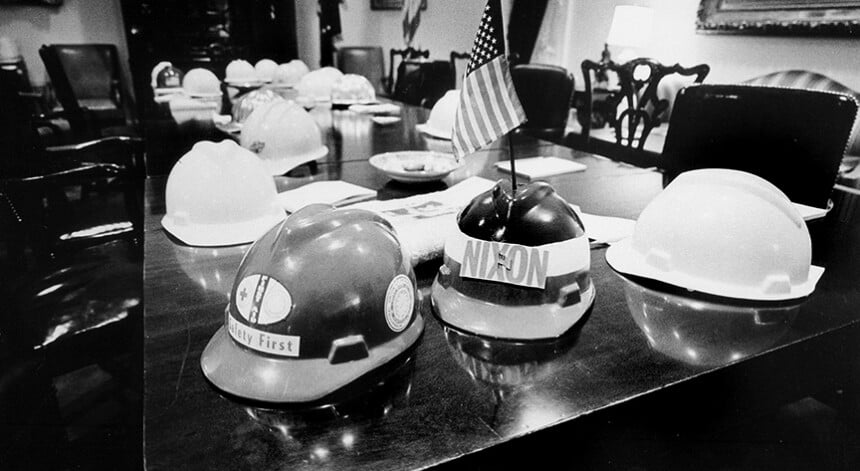

Image Credit:

above: hard hats on cabinet table after Nixon meeting with construction trades group on May 26, 1970, less than three weeks after the New York City Hard Hat Riot (National Archives)

Leave a Reply