“Where law ends, tyranny begins.”

—William Pitt

On the eve of the inauguration of the second Clinton administration, reading biographies of the First Couple is like reading Airport while waiting to board a transcontinental flight. A morbid interest in gruesome facts and events is further titillated by the anticipation of horrors to come. Nevertheless there is comfort in reflecting that, barring the President’s assassination or an attempt by him at a coup organized by uniformed homosexuals of both sexes, both he and his wife, 50 years hence, will be as little remembered or marked by history as President Franklin Pierce and . . . he was a bachelor, wasn’t he?

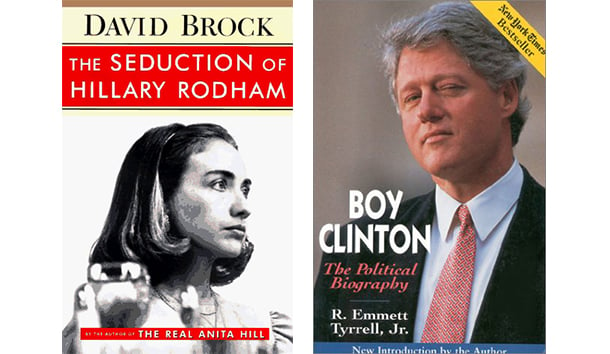

Emmett Tyrrell’s and David Brock’s books contain fresh facts while training differently angled lights on their subjects, but in the end they largely confirm what was already known, perceived, and suspected about Bill and Hillary Clinton. Still, it is not entirely clear to me that anything more was really necessary, or possible; what these authors do, moreover, they do ver)’ well. Taken together, Boy Clinton and The Seduction of Hillary Rodham demonstrate conclusively that the first “co-candidacy,” and later the first “co-presidency,” in American history (excepting only Richard Nixon’s well known compact with the Devil) has been a yoking not just of the consummate politician with the driving ideologue but of the worst of American political opposites—the Yale Law School and the state of Arkansas—to elevate and refine the American kakistocracy to a hitherto unimaginable perfection. Whether Bill Clinton moved up in going to New Haven, and Hillary Rodham moved down in following him back to Hot Springs, is not a question worth arguing. According to Mr. Tyrrell, Yale and Oxford radicalism was “the cultural semen that accounts for President Bill Clinton; its egg is in Arkansas”; as, for his wife, Wellesley and Yale were the egg that produced her, its semen being the corrupt, one-party system of government operating from Little Rock.

Tyrrell certainly has the goods on Mr. Clinton, so far at least as the facts of his malfeasance, in Washington, D.C., and in Arkansas, can be known and inferred; of particular interest are his revelations concerning drug-smuggling operations at the tiny airport at Mena. More valuable in assessing the political phenomenon that is Bill Clinton, though, is his insight into the narcissistic compulsive mania that is the secret of Clinton’s political success, nationally as in Arkansas. Having noted the young governor’s slight legislative successes over six terms, which prefigure future presidential sterility in Washington, Tyrrell argues that the chief reason for Clinton’s failure to pursue his initiatives to their conclusion was his disinclination to be less than all things to all men (and all women). Invoking what he calls the “Chronic Campaigner,” Tyrrell suggests that Clinton is in this respect representative of other successful politicians of his generation, not an exception from them. “Past politicians enjoyed wielding power for high purpose or low gain. They were more apt to take risks and face defeat. Though he usually devotes more energy to politics, the Chronic Campaigner takes fewer risks.” He adds astutely, “For years the Chronic Campaigner has been handing over power to bureaucrats, to judges, to anyone who will protect him from having to make a potentially unpopular decision so that elected officials no longer have the power that they once had.” Perhaps George Will has this development in mind when he refers to the “miniaturization of the Presidency.” As Tyrrell reflects, “[the Clintons] almost always settle for a semblance of power.” At least, Mr. Clinton does. What seems likely is that the Chronic Campaigner is a product of the sensate culture with its cult of personal celebrity and its search for the endless high. “Clinton,” Tyrrell says, “is a very reckless man. . . . [He] is not courageous, but he seems always to have been a daredevil.”

Another reason for Clinton’s desire to be on both sides of every issue, Tyrrell explains, is the determination of the “Coat and Tie radicals” of the 1960’s and 70’s to “have it all.” With that determination comes an “incomparable capacity for double-talk,” and also a prehensile ability —shared by old associates of Clinton’s like Ira Magaziner, Robert Reich, Mickey Kantor, and his own wife—to market themselves without having actually produced anything. It is hard to say whether the ubiquity and influence of politicians like these creates or reflects a characteristic of the electorate observed after the 1996 elections by Maureen Dowd, when she wrote that Americans apparently want liberal politicians who are really conservatives, and conservative politicians who are actually liberals. In any case, Tyrrell is surely correct in concluding that the 60’s radicals’ combination of amorality with self-righteousness is having historic consequences. “So closely have they identified with all the good causes they have espoused that at some point in their development they assumed that they themselves were good causes.”

They were, in other words, self-seduced: a form of seduction that seems not to have occurred to Mr. Brock, whose sensitive and balanced treatment crosses the line at times to play the Devil’s advocate. Bill Clinton’s First Lady, he insists, is “not a phony,” but fundamentally a “good person” led substantially astray by a variety of bad influences, the greatest of which is Bill Clinton himself. The major weakness of this meticulously researched, well-written, interesting, and agreeably humane book is that its principal thesis belongs to the little-bit-pregnant school of moral reasoning. One cannot, first of all, be seduced unless at least half of oneself acquiesces in the seduction (“Vorrei e non vorrei; . . . “). Secondly, had The Seduction of Hillary Rodham not occurred as Brock describes it, what then would she be today? Certainly not the First Lady of the United States. Otherwise, it is impossible to imagine her much differently from David Brock’s evocation.

As Brock tells it, the irresistible temptations to which Mrs. Clinton proved unequal include the influence of a Methodist minister who urged her to read the Bible as a basis for political action and pointed out the similarities between communism and the Christian faith; the political theory of Saul Alinsky, the Machiavellian organizer who persuaded several generations of activists that the ends always justify the means, and that law is simply the instrument of the ruling class; “Boy Clinton,” the attractive narcissist who went about the Yale quad telling people he was going to be President of the United States some day; Marian Wright Edelman, who taught her to think of government as an instrument of virtue and a tool for social progress; her tenure as chairman of the Legal Services Corporation when, in protracted confrontation with the Reagan administration which sought to curtail the LSC’s activities, she took shortcuts across the rules in order to achieve what she conceived to be noble ends; the one-party system in Arkansas, breeding “a certain moral arrogance and carelessness about any appearance of impropriety or possible ethical lapse”; and, finally, the prospect of attaining her life’s ambition by following a script rewritten by her husband’s handlers in 1992 to make her more appealing to the conservative majority of the American public. Had these temptations not arisen, or had Hillary Rodham found strength to cry, “Get thee behind me, Satan!” at the climax of her moral crises, then. Brock suggests, things might have turned out differently. How differently? Well, her expertise acquired from her work with the LSC, the Children’s Defense Fund, and the New World Foundation might eventually have won her a federal judgeship, or a seat in the Senate. Maybe it would have; then again, perhaps it wouldn’t. The trouble with this line of argument is, if Hillary had had it in her to reject her various temptations, then she wouldn’t be Hillary but some other woman, whether judge, senator. First Lady, or the first female drill sergeant at the Virginia Military Institute. The What If approach is, if anything, even less promising when applied to biography than it is to the study of history. Like everyone else in the world, Hillary Clinton, having made her bed, now must lie in it, even if it has been known to accommodate four or five people at a time.

Brock’s reading of the Clintons’ partnership indeed suggests a certain inevitability, a fatedness. “The co-candidacy . . . may best be understood not as a cold political bargain but as a kind of codependency. Bill and Hillary not only complemented one another in a remarkable way: over time they came to seem eerily necessary to one another, as though neither can really exist or succeed on their own.” Brock’s account leaves absolutely no doubt that without benefit of his wife’s practical efforts and hardheaded political astuteness, the Chronic Campaigner would neither have retaken the governorship in the 1982 race that made the later presidential run possible, nor would he in all likelihood have succeeded in his bid for the presidency. On the other hand, lacking almost entirely her husband’s personal charm and appeal to the voters, Hillary must have recognized that electoral politics, practiced in her own right, was not the means to the political power and influence that she sought. So, in addition to fatedness, there remains the matter of convenience as a principal factor in the Clintons’ unconventional marriage. The more we learn of the Clintons, it seems, the more nothing about them changes.

So far as the Whitewater scandal goes. Brock makes the best defense for Mrs. Clinton that we are likely to hear outside a court of law with a very high-priced attorney arguing on her behalf. Hillary Clinton, he suggests, knowing little of her husband’s dealings with James McDougal but having allowed herself to be compromised by the Arkansas mob into which she had married, was willing to risk the appearance of wrongdoing by representing Madison Guaranty; later, when accused of the doing itself, she engaged in what may have been illegal tactics to cover over the appearance. Since charges of influence-peddling and money-grubbing have registered hardest with the cohort of disillusioned feminist professional women who were formerly among the First Lady’s greatest admirers, Brock makes a particular point of stating his belief that Hillary Clinton is no phony. “Hillary has been nothing if not up-front about what she stands for, but the mainstream press has been unreliable in reporting on her real views and also in explaining the extent to which Hillary is the ideological engine driving the co-candidacy.”

Unfortunately, Brock’s own book contradicts this claim. For instance, Hillary Rodham was not up-front when she misrepresented to Congress what the Legal Services Corporation was really up to, what it wanted all that money for; nor had she, along with her colleagues on John Dear’s Watergate Committee, been up-front in the Committee’s representations to the House Judiciary Committee of which it was an adjunct. Granted, she was absolutely candid meeting in camera on a variety of leftwing appointive committees—but not always outside those committees, and hardly at all in electoral politics, where she has often kept mum and submerged herself from view in preference to speaking her mind. It is fair to say, then, that whereas Bill Clinton is always a phony, Hillary Clinton is a phony only when she thinks she has to be—which is a great deal of the time. The closer she has approached to power, moreover, the less forthright and more open to seduction has she become.

Hillary Clinton, in Brock’s view, is “a revolutionary—though a type of revolutionary that is not easily recognized by most Americans. She is a ‘soft’ revolutionary—or ‘establishment’ radical—of the kind that thrives today in the social democracies of Western Europe and Scandinavia.” Bill Clinton, for Brock, is the pathetic product of an alcoholic home, a compulsive liar and philanderer who wants to be admired by every man in the world and loved by every woman: an operator with no ideas, political or otherwise, and no legislative agenda other than that of his wife and what Bruce Lindsay once called her little friends. The President’s way is the Arkansas way: power as a means of acquiring boodle, influence, free sex, and cheap drugs. The co-President’s way is the Alinsky way: power in order to abuse the law for the purpose of tearing society down, as if it were a quaint historical neighborhood, and replacing it with a high-rise project whose inhabitants are closely regulated by an absentee management. Between the two styles of government, it seems to me, the Arkansas one is infinitely preferable; yet, as things stand, we can look forward to a combination of the two, another four-year partnership between Harry Thomasson and Doris Meissner. The question is not whether, as conservative critics have recently argued, the American legal structure has been tortured into illegitimacy by ideological politicians and judges, but whether the government itself, staffed by an anti-American personnel, is today the deadly enemy of the American people and their interests.

[The Seduction of Hillary Rodham, by David Brock (New York: The Free Press) 452 pp., $26.00]

[Boy Clinton: The Political Biography, by R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc.) 356 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply