The publication of Gone With the Wind in 1936 was a major event in publishing—if not literary—history, compounded by the overblown movie of 1939 and by worldwide sales that continue to this day. Margaret Mitchell was overwhelmed by the reaction, which was complex and multifold. The novel was read by people on both sides in the Spanish Civil War, and Mitchell received all sorts of letters showing she had struck a nerve. One German thought that she had intuited his experience of World War I and the economic slump that followed, and a French town wanted to make her a citizen. The resistance to Gone With the Wind seems to have come mostly from the Nazi Party, the Communist Party, and American liberals—a suggestive convergence. Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, perhaps the greatest novel ever written by an American, was passed over for the Pulitzer Prize, swamped by the massive phenomenon of GWTW. Dissenters did object to the novel on racial and historical grounds: the stereotyping of blacks and the “Southern” rendering of Reconstruction.

The whole matter is of considerable interest, embracing as it does the problematics of writing and representation as well as controversial episodes in American history; still, we must admit that it is limited by the passing of the years. There comes a point when Scarlett O’Hara (or “Scarla O’Horror,” as she is referred to in John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces) seems as quaint as Becky Sharp, on whom she was modeled. Been there, done that—though I must concede that I have met four women who were, or are, obsessed with Scarlett O’Hara. Three of them thought she was a great “female role model,” which shows some of the depth of the book’s insidious perversity. The poison in the heart of Scarlett O’Hara remains a challenge for some, giving us insight into the obsessive contamination inherent in this massive narrative about obsession.

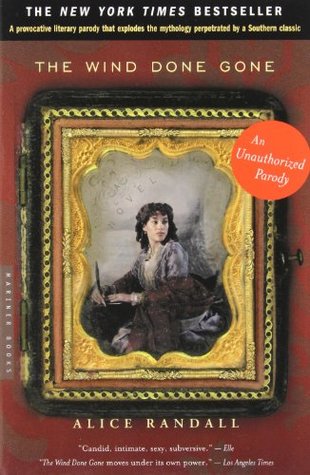

Cashing in on GWTW is big business, that’s for sure. Acting in the spirit of Scarlett O’Hara—if not of Margaret Mitchell—the Mitchell estate authorized the inert Scarlett by Alexandra Ripley in 1991 and has since had trouble arranging a sequel to that sequel. This year, Mitchell’s heirs went to court to block the publication of Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone on the grounds that it was an invasion of copyright; they lost when the judge upheld the publishers’ claim that the book is a parody—”The Unauthorized Parody,” as the dust jacket blares. That may be slick lawyering, but The Wind Done Gone is no parody. It is rather a rip-off and a revision, and a feeble and mechanical one at that.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with a parody, if indeed The Wind Done Gone were one. And the tradition of revision is indeed the “inadvertent epic” that Leslie Fiedler has brilliantly claimed to be the core of the American tradition of sadomasochistic, racially inflamed melodrama, from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to The Clansman to GWTW to Roots. Though there was much of mawkishness, there was no parodistic sense in that progression—quite the opposite, since a sense of humor would have ruined all the hokey solemnity and seriousness. Revision requires strength, imagination, and conviction, none of which are to be found in The Wind Done Gone.

Alice Randall’s little squib is fatally dependent on the monumental model that it affects to invert. The bookette is the diary of Cynara, the mulatto half-sister of Scarlett (“Other”), by Mr. O’Hara out of Mammy. Cynara is the mistress of “R” (guess who!), the Dreamy Gentleman (guess again) is gay, and Cynara goes with a black senator to Washington. The diary form, obviously adopted to avoid the work of creating a narrative, is disastrous to the novel; and though this book can be downed in one sitting, there is no reason to do so, the revisionary work having been done so many times—and better—by authors black and white. Miss Randall was laboring not only in the shadow of Faulkner but of Robert Penn Warren [Band of Angels), not to mention Margaret Walker Alexander (Jubilee), Frank Yerby, and so on. And the recent film Adanggaman by Roger Gnoan M’Bala, portraying blacks enslaved by blacks in 17th-century Africa, is a powerful and provocative treatment of a subject that has been dealt with all too gingerly.

It makes sense that our history should be reinterpreted fictionally. But if GWTW is “offensive,” then revision of that offense will require more than Alice Randall has given. If Gone With the Wind is a still a “problem,” our nation must be in better shape than I had dared to hope.

[The Wind Done Gone, by Alice Randall (New York: Houghton Mifflin) 208 pp., $22.00]

Leave a Reply