Freudian Fraud has an intriguing but difficult-to-prove thesis, namely that Freudian thought radically altered American society for the worse. An “audit of Freud’s American account,” says Torrey, shows more debits than credits. He believes the chief liability inherent in the Freudian system is its tendency to undermine traditional notions of responsibility.

“Don’t blame me, blame my parents” has been a constant refrain in American therapy and American life ever since Freud’s ideas came to these shores. As Torrey points out in a chapter on the Freudianization of criminology, it was just such a defense that was put forward in the sensational Leopold-Loeb trial of 1924. Defense lawyer Clarence Darrow simply passed the buck for the crime onto the parents of Leopold and Loeb. William Hanson White, one of the three psychiatrists who testified for the defense later called for “the discarding of the concept of responsibility” for criminal behavior. The same theme of nonresponsibility, says Torrey, can be found in current therapy fads such as the inner-child movement. He quotes John Bradshaw, one of the movement leaders, as saying, “A lot of what we consider to be normal parenting is actually abusive.” In Torrey’s view, however, adults have more important things to do than lick their childhood wounds.

In tracing the history of Freudian thought in American culture, Torrey succeeds in showing the presence of influential Freudians at crucial junctures and crucial places: in Greenwich Village in the teens and early 20’s, on the staff of the Partisan Review in the 30’s and 40’s, in Hollywood in the 40’s and 50’s, among campus radicals in the 60’s (via the influence of Herbert Marcuse, Norman O. Brown, and Paul Goodman). He also traces the influence of Freud on child care (mainly through the writings of Benjamin Spock) and on criminology (the chief carrier in this case being Karl Menninger). He attempts, in addition, to tie the ups and downs of Freudianism to larger historical forces. The fortunes of the Freudian faith took a tumble with the ascendancy of genetic theories in the 20’s, then rose again in the 30’s when those same theories became identified with Nazism. The Nazi period also saw a significant transfer of European psychoanalysts to America, and this, Torrey suggests, is the main reason Freudian theory took its strongest root in this country.

Torrey’s discussions of “race, immigration and the nature-nurture debate” and of “the sexual politics of Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead” are among the most interesting in the book. We learn about anthropologist Franz Boas’s battle with the “Anglo elite,” the role of the Depression in forcing newly poor Americans to question the genetic theory of poverty, and the great success of Boas’s proteges, Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict, in bringing victory to the nature side of the nature-nurture controversy. Torrey makes a convincing case that both Mead and Benedict allowed their work to be influenced by personal sexual agendas and that both were shoddy researchers. Benedict had no firsthand knowledge of two of the three cultures she compared in Patterns of Culture, and Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa seems to have been based on gross disinformation.

These excursions into anthropology are so interesting that one almost forgets to ask a basic question: where does Freud fit in? Although Torrey establishes the existence of a strong Freudian influence on Boas, Mead, and Benedict, he fails to convince that their work is mainly an effect of Freudianism. One could, for example, argue that the influence of Rousseau on the American anthropologists was just as powerful as the influence of Freud.

The main problem with Torrey’s analysis is that, in order to make his ease, he often reduces Freudianism to one main idea: the determinative nature of early childhood experiences. If Freudianism is taken to mean that and nothing else, then his ease holds up. But his thesis is somewhat less tenable when we consider the wide-ranging and complex nature of Freud’s thought. For example, much of what Freud had to say about civilization and repression is at the opposite pole from Margaret Mead’s views on the same subjects. Some of Torrey’s complaints seem more appropriately directed at popularizers of Freud than at Freud himself.

Nevertheless, Torrey, whose earlier book on the psychiatric incarceration of Ezra Pound is highly regarded, deserves to be taken seriously. Freudian Fraud raises important and provocative questions about the influence of psychoanalytic theory on American culture. While one can disagree with Torrey about the degree and scope of that influence, it is difficult to deny that in the course of this century—which Torrey calls the “Freudian century”—we have exchanged a good deal of practical wisdom about the conduct of life for a good deal of highly speculative notions that have only served to make our lives more complicated than they need to be.

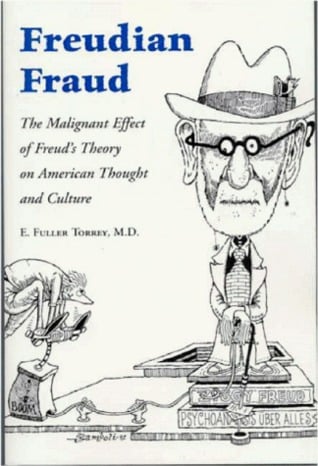

[Freudian Fraud: The Malignant Effect of Freud’s Theory on American Thought and Culture, by E. Fuller Torrey, M.D. (New York: HarperCollins) 362 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply