” . . . Form and Limit belong to the Good.”

—C.S. Lewis

Liberals in the United States have lately gathered around the standard of pluralism in the hope of stalling the movement toward private Christian education. Yet Americans, historically indifferent to such objections, have been the last to censure a church—especially a reformed or an evangelical one—for its forays into schooling. Essentially we are a religious people. Our traditions, symbols, and character carry the stamp of the pulpiteer. Listen to almost any group of Americans conversing on a topic that requires taking sides (and, given the American character, few topics don’t), and you will pick up first the high moral tone, second a trace of righteous anger, and finally the hammer of condemnation. When an American thinks he’s right, he stands on the mountaintop with a thunderbolt in hand and challenges all comers. Such an attitude must perplex and irritate foreigners—notably Western Europeans—just as the lack of it in them galls us; yet an American without it would hardly seem worthy of the name.

We are all preachers at heart The New Englander finds himself alternately haunted and inspired by images of the glorious City on the Hill; and the Southerner surely sees nothing strange in the offshoot of the Great Awakening, the revival. But whether we trace our origins to Plymouth Rock or Jamestown, we find the same thing: a group of men dedicated to serving God, And not just any God. Jefferson and Paine could talk all they wanted about Nature’s God, but outside their small circle, men had much more definite ideas about who God was and what He expected. The God of the men who fought in the Revolution and ratified the Constitution was the God of Abraham and Paul, the God of the Bible, sharply defined as Savior and judge, and specific in His commandments. Behind this piety was always a sure reverence for the Word, divinely inspired and, in the minds of most men of the time, unambiguous.

Generations of young Americans were educated to revere the God of Scripture, to invoke Him in time of need, to fight for Him if necessary. It is no accident that Harvard and Yale were founded to promote the art of preaching, biblical exegesis, and missionary zeal; that Princeton once chose Jonathan Edwards to serve as its president; that Lincoln in his Second Inaugural Address invoked not the God of Nature but the God of the Bible; or that historian and statesman Albert Beveridge confidently declared before the U,S, Senate near 1900 that America was God’s chosen nation. Such behavior was what Americans had come to expect of their leaders; they educated their children to insure they would act similarly.

To attempt to skirt the role of religion in the history of American education, as indeed many contemporary pedagogues are trying to do, is to remain ignorant of the central fact of our background. Yet this ignorance has come to dominate the community of intellectuals and pedagogues who have assigned themselves the task of interpreting and chronicling our country’s past, as well as its relationship to the present and future. Their “pluralism” (translated in the extreme into nihilism) quite logically follows from their inability to accept the traditional American adherence to biblical precepts. For them, the American tradition is 20th-century secularism and relativism read into the past. The absolute limits of our worldly condition clearly delineated in the Christian doctrines of the Fall, damnation, and redemption—doctrines once carefully taught our young—are treated as foreign to the American genius.

That Christian schooling, as practiced by the evangelical and reformed communities in this country, is anathema in this community is shown in two recent additions to pedagogical research, Alan Peshkin’s God’s Choice and Peter McLaren’s Schooling as a Ritual Performance. Though pursuing different purpose and theory, each author displays a frame of mind characteristically hostile to or perplexed by the revival of educational techniques that formerly served America.

Peter McLaren, a Canadian, addresses his work to the problems of lower-class Azorean students in a Catholic school in Toronto. It would seem, then, that Schooling as a Ritual Performance has little to do with the future of American education. Regarding the particulars of the book, this is correct. Theory, however, has no respect for borders; it is reasonable to suppose that McLaren would develop similar ideas and phobias in an American setting. Anyhow, McLaren clearly means to address his conclusions to the fraternity of Western educators in general and not merely to a restricted group.

Even though McLaren never explicitly proposes to debunk traditional Christian education, that is exactly what he ends up doing. In studying the treatment of Portuguese junior-high students in Toronto, he arrives at the not-too-novel conclusion that Catholic educators, wittingly or unwittingly, are engaged in bolstering an inherently evil capitalist society. How, one may ask, are they doing this? The answer will not surprise anyone, for it is as worn as McLaren’s costive deconstructionist lingo. As instigators of an established classroom (and class) ritual, the teachers become agents of “class domination” resulting in the “reproduction of inequality.” They are able to do this by equating model student behavior with model Catholic behavior. If a student is a good Catholic, he will work hard to prepare himself for a life working in a factory or driving a truck. Thus school and Church provide grist for the capitalist mill. In pursuing this line of reasoning, McLaren never calls religion the opiate of the people, but he might as well.

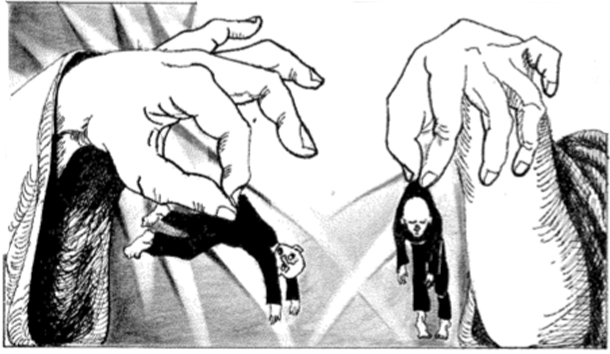

In constructing—or deconstructing—this insipid Marxist critique for nearly 300 pages, McLaren manages one good point. He rightly asserts that educators, apparently as much in Canada as in America, have reduced schooling to job training at the expense of moral nurturing. But such a critique requires a careful examination of w/idt teachers teach. An educationist first and last, McLaren cannot bring himself to go beyond the how of ritual and method. He prefers to challenge educators to “develop a curriculum of cultural politics [that] runs athwart the logic of capital and the hegemonic hold of Late Capitalism.” This task will involve the “deconstruction and displacement . . . of the centrality of symbolic manipulation and moral violence . . . which is necessary in order to promote the insurrection of subjugated student voice and the creation of a pedagogy of self-empowerment. ” Reading such statements, one is left with the uneasy feeling that the power in “empowerment” exists for no other reason than to be exercised. If so, McLaren’s ritual and method are really metaphors for manipulation and control. The only question is who will do the controlling.

This is what results when mere power and liberation replace the virtue and piety Christianity once supplied. Classroom norms, such as obeying teachers, working diligently, paying attention, telling the truth, and growing up—once regarded as absolute goods—suddenly acquire the ominous label “the structure of conformity.” Goofing off in class becomes “the antistructure of resistance.” (What happens to an orderly class where some teaching might really be done is anybody’s guess.)The nihilism implicit in this inversion of meaning does not seem to worry McLaren. In such a world he glimpses a hazy Utopian future where “knowledge and freedom meet once and forever.” Yet, again, without the defining, limiting Word, this project leads only to the abyss McLaren hopes to span. It is in fact the death of real freedom and morality.

Alan Peshkin’s God’s Choice is a less disturbing book than McLaren’s. It is a straightforward presentation of Peshkin’s findings on evangelical Christian education, focusing on one Bethany Baptist Academy in “Hartney,” Illinois. Peshkin notes that important as pure academics are at Bethany, morality is the first concern of the teachers. Moreover, the system works amazingly well, since the students and teachers obey the rules of Scripture. Bethany’s students tend to graduate “as loyal, honest, hard-working, punctual, and reliable young adults.” They revere God, accept Christ as their Savior, regard robbery, lying, and cheating as sins, frown on drugs, and show every indication of carrying these beliefs into maturity. To his credit, Peshkin does not appear to find any traces of “the hegemonic hold of Late Capitalism” in these virtues and concludes that fundamentalist Christian schooling, though not an absolute good, is a qualified good.

All is not rosy, however, in God’s Choice. For one thing, Peshkin betrays a surprising ignorance of the Bible (Old and New Testaments)—an odd trait for a man who is both a Jew and an American. Doctrines such as the Fall and God’s sovereignty seem never to have crossed his mind. This sort of theological and cultural amnesia would have been impossible for the average high-school student 50 years ago. That a sensitive and intelligent university professor should display a near complete ignorance of such matters reveals the gulf separating the academic community from the Christian tradition.

Next and equally unsettling is Peshkin’s inevitable cry for pluralism, which he sees as the only safeguard against a Christian persecution of non-Christians. What Peshkin doesn’t realize is that pluralism, designated nowadays the ultimate civic virtue, can easily lead to amorality opening the door to discordant variations on the theme of power: terror and tyranny. In the absence of the divine Word, the authority to permit certain acts and forbid others loses its ability to direct the minds of men toward the good.

To a great extent, the nihilism that undergirds the politics of power has the West in a stranglehold. Books like Schooling as a Ritual Performance are evidence of its grip. The one glimmer of hope in American and, hence, Western education is the Christian school. Christianity, far from establishing dictatorships, prevents them by subjecting all men to a final arbiter and by limiting the scope of men’s deeds with the rule of law. The American ethos has implicitly rested on the moral basis most commonly taught in Christian schools. It may be possible to destroy that ethos; it is impossible to remain free and preserve our American character without it. Peshkin’s cautious admiration of Christian education suggests a faint grasp of this fact. The sooner others grasp it, the better for all of us.

[Schooling as a Ritual Performance: Towards a Political Economy of Educational Symbols and Gestures, by Peter McLaren; London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul]

[God’s Choice: The Total World of a Fundamentalist Christian School, by Alan Peshkin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) $24.95]

Leave a Reply