“The ‘Tycoon.'”

—J.G. Nicolay and John Hay

(Secretarial nickname for President A. Lincoln)

In the foreword to Brother to Dragons , Robert Penn Warren writes “historical sense and poetic sense should not, in the end, be contradictory, for if poetry is the little myth we make, history is the big myth we live, and in our living, constantly remake.” This statement seems particularly relevant to the persona of our 16th president. Whenever mainstream historians rate our greatest chief executives, Abraham Lincoln is usually ranked first—because he saved the union and freed the slaves. (Whether those objectives could have been accomplished by some measure short of a war that cost 600,000 lives is a question rarely asked by Lincoln hagiographers.) Often with little understanding of the historical figure and what he really believed, political opportunists from the far left to the neoconservative right claim the Lincoln legacy. When American Stalinists went to Spain to fight for its communist government in the 1930’s, they formed the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. When Newt Gingrich wanted to launder money for his partisan purposes six decades later, he used a dummy foundation for underprivileged black children named after the Great Emancipator. It can be said of Lincoln what Orwell said of Dickens: he is “well worth stealing.”

But Lincoln is far more than the most widely coveted patron saint in American politics. He has come to embody our national identity to the point that his legend is virtually synonymous with the big myth we live. Thanks to literary gushmeisters from Walt Whitman to James Agee, he is also an abiding presence in the little myth we make. When Americans of a certain age think of Lincoln, they see Raymond Massey in the film version of Robert E. Sherwood’s reverential Abe Lincoln in Illinois. (With little change in characterization, Massey later played John Brown in The Sante Fe Trail.) Even Southern partisans such as Thomas Dixon, Jr., and D.W. Griffith have gotten in on the act by portraying Lincoln as “the Great Heart” who would have welcomed the Confederate states back into the union much as the forgiving father celebrated his prodigal son’s return to the old homestead.

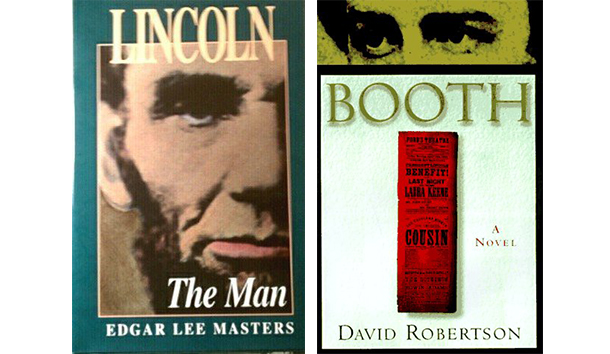

While George Washington had his Parson Weems, Lincoln was blessed with an even more talented myth doctor in the prairie populist Carl Sandburg. In his six-volume beatification of Lincoln, Sandburg assured us that humble beginnings and lifelong adversity could not suppress true greatness in this most democratic of nations. The vision of America as a classless meritocracy is as old as Ben Franklin and as recent as Lee Iacocca, but Lincoln’s passage from the log cabin to the White House is its most memorable embodiment. In being both extraordinary and representative, Sandburg’s Lincoln is the perfect American hero. But in between the appearance of Sandburg’s first two volumes (The Prairie Years in 1926) and his last four (The War Years in 1939), another prominent American poet, Edgar Lee Masters, published Lincoln, The Man. This book, first released in 1931, has been as vilified as Sandburg’s has been celebrated. Now that it is once again in print, thanks to the Foundation for American Education, we can see why.

Born in Garnett, Kansas, in 1868, Masters grew up in Petersburg and Lewistown, Illinois. He was thus of a time and place to have known several individuals intimately acquainted with Lincoln in his pre-Mount Rushmore days. The most important of these was William Herndon, who had been a law partner of both Lincoln and Edgar’s father, Hardin Masters. Up to the age of 43, Edgar Lee Masters himself pursued the profession of law. In 1892, after a year of college, he passed the Illinois bar and moved to Chicago, where he eventually formed a partnership with Clarence Darrow, which lasted from 1903 to 1911. Like his fellow Midwesterner Sherwood Anderson, Masters abandoned a conventional career in middle age to follow the literary muse. His reputation rests largely on Spoon River Anthology, a collection of poems published in serialized form in 1914 and 1915.

Although Masters is often lumped with Vachel Lindsay and his fellow Lincolnographer Carl Sandburg, two poets born in Illinois a decade after Masters, his sensibility was radically different from theirs. Sandburg and Lindsay, like Whitman before them, subscribed to a kind of mystical populism, which romanticized a collective abstraction known as “the people.” (One of Sandburg’s most characteristic collections of verse was entitled The People, Yes.) Both poets proudly positioned themselves on the left wing of the political spectrum. In contrast. Masters was a states’ rights populist. Neither as poet nor political thinker did he ever view “the people” apart from their rooted lives in a local community. Masters was also an anti-romantic realist. In Spoon River Anthology, the dead (William Herndon and Ann Rutledge among them) speak from beyond the grave, often in contradiction of the pious epitaphs inscribed on their tombstones. In much the same vein, Lincoln, The Man is a work of monumental impiety.

Masters uncovers no significant new information regarding Lincoln. At the outset, he freely confesses his debt to two previous Lincoln biographers, Albert Beveridge and his old family friend William Herndon. (Time claimed that Masters had written the 112th life story of the Great Heart.) Masters is interested less in rehashing known facts (although he does plenty of that in this 500-page tome) than in arguing for a particular, and highly unfashionable, interpretation of Lincoln’s life. Citing such Confederate texts as Pollard’s The Lost Cause, Stephens’ Constitutional View of the War, and the work of Jefferson Davis, Masters writes:

These could call Lincoln a sophist and a usurper, only to be smiled at by the rich and populous North, the North of poets and historians, and great captains, and the statesmen of a new regime of political control, of a government made a nation from a confederacy of states by the glorious acts of an army headed by Lincoln!

These are the words of a copperhead who, like his contemporary Robert Lee Frost, never forgot that he was named in part for a figure of Southern myth.

Lincoln may have been a poor boy (Masters stops just short of branding him white trash), but his economic views were always in sympathy with the monied interests. Masters traces his philosophical lineage to Alexander Hamilton, a would-be aristocrat who could never quite erase his origins as a “West Indian bastard.” Lincoln’s own great hero was the senatorial deal-maker and national compromiser Henry Clay. A sort of 19th-century Bob Dole, Clay believed in a mutually beneficial partnership between corporate wealth and a highly centralized federal government. Like his fellow Whigs, Lincoln supported a national bank, high tariffs, and “internal improvements.” Had he been brighter and more industrious, he probably would have ended his days finessing the law for some predator}’ robber baron rather than trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.

If Masters has nothing but contempt for Lincoln’s Whiggish sympathies, he attributes all sweetness and light to the agrarian tradition exemplified by Thomas Jefferson. (Lincoln, The Man appeared less than a year after I’ll Take My Stand and received one of its most positive reviews from Andrew Lytle in the Virginia Quarterly Review.) Wishing to leave no doubt about his own political loyalties. Masters dedicates his book “To the Memory of Thomas Jefferson.” He sees the Lincoln administration as the final triumph of economic and political centralization —in short, of the Hamiltonian vision. “The history of America since the day of Lincoln,” Masters concludes, “has been nothing but a filling in of the outlines of implied powers, which Lincoln did more than even Hamilton or Webster to vitalize; it has been nothing but further marches into the paths which he surveyed toward empire and privilege.”

Not content with reviling Lincoln’s politics. Masters finds fault with virtually every aspect of his character. Praying and reading the Bible while belonging to no church, Lincoln, in Masters’ view, possessed all the vices but none of the virtues of a religious fanatic. Unrestrained by any theology, he saw himself as the instrument of God’s will and used biblical rhetoric to sanctify actions that fell beyond the bounds of human justice and prudence. Lacking in normal human sympathy, he refused to visit his father’s deathbed. Even the story of his love affair with the doomed Ann Rutledge (which Masters himself did much to promote in Spoon River Anthology) is judged improbable. When he agreed to wed Mary Todd, he initially stood her up at the altar. Mary, however, was not to be denied. Like Hillary Rodham more than a century later, she was an ambitious girl from Illinois who saw the makings of a future President in what others took to be nothing more than a pushy bumpkin.

Masters is such a thoroughgoing iconoclast (or “Lincolnoclast,” as Time called him) that one is left wondering how such a banal mediocrity as Lincoln could have become the most influential political figure of the past two centuries. One would think that it requires superior abilities to accomplish great evil; however, the Lincoln Masters gives us seems no more prepossessing than the eminently forgettable figures who preceded and followed him in the White House. Thus, in explaining Lincoln the man, Masters leaves the myth that the man spawned more inexplicable than ever.

If Father Abraham remains our national god, then the man who shot him is surely the American Antichrist. Because demons are usually more interesting than deities, one approaches David Robertson’s novel Booth with high expectations. Following the example of Gore Vidal in Burr, Robertson rewrites an important chapter in American history from the ostensible villain’s perspective. But Robertson does not portray John Wilkes Booth as a martyr or even try to elicit our sympathy for this deeply troubled man. Indeed, he shows us that Lincoln was not the only casualty of Booth’s dementia. Like the Prince of Darkness himself. Booth had the power to assume a pleasing shape, and he used that power to con some of life’s losers into doing his bidding. Today, we are apt to think of political assassins as anonymous wretches desperate to achieve notoriety by gunning down a public figure. Booth, however, was a celebrity long before his fatal encounter with Lincoln. It was his co-conspirators—Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt—who more closely resembled the Lee Harvey Oswalds and James Earl Rays of our time. Booth was more like O.J. Simpson with a political agenda.

Robertson tells his story through the voice of John Surratt, the most normal and the longest-lived of the Booth conspirators. When Robertson began work on his novel, he was struck by the fact that Surratt, who died in 1916, lived long enough to have seen Lincoln’s assassination depicted in D.W. Griffith’s classic film The Birth of a Nation, which premiered in 1915. Robertson therefore sets his novel in April 1916, less than a week before Surratt’s death, and introduces the filmmaker as a character in the book; Griffith’s attempts to enlist Surratt’s aid in a movie on Lincoln that he is contemplating (and which was actually produced) cause Surratt to reflect on the events of over half a century earlier.

Booth’s perverse power, as Robertson depicts it, lies in his ability to satisfy the vicarious needs of others. Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt were all skid-row types who had been destroyed by either the war or life itself In playing the role of patron and surrogate brother to these young men, the glamorous Booth captured their unquestioning loyalty. Although the fatherless John Surratt also fell prey to Booth’s charm and benefited from his influence, he placed limits on both his devotion and his service. Consequently, he is the perfect narrator for this book—a character who is involved with the main action but stands at a sufficient distance to comment honestly on it. (It also helps that he survived into the second decade of the next century.)

The most aggrieved character in Robertson’s narrative (as well as in historical fact) is John Surratt’s mother, Mary. One of only a handful of women ever executed by the federal government, Mrs. Surratt was almost certainly guilty of nothing more than having known John Wilkes Booth. Even in the brief affair that Robertson imagines between her and Booth, Mary comes off as a lonely widow whose temporary weakness of the flesh brings her more anguish than pleasure. The affair, in turn, motivates John Surratt’s break with Booth.

Initially, one is encouraged to see Booth as a man deluded into thinking that his quixotic plot to kidnap Lincoln will bring an end to the national bloodshed. Once peace is declared, however. Booth must murder the President, ostensibly to redeem the honor of the South, but actually to play out a personal death wish. Up to the last moments of his life. Booth is a more consummate actor offstage than on. Whether with the men who shared his false friendship or the women who shared his bed. Booth always knew how to play an audience. His betrayal of the people who felt closest to him ultimately seems more real and more damning than any wrong he inflicted on a nation he never claimed to love. If, as many historians believe, Reconstruction was harsher because of Lincoln’s death, the final victim of Booth’s treachery was the South itself.

If his encounter with Booth was the worst thing that could have happened to Lincoln the man, it was one of the best things that could have befallen Lincoln the myth. One can only speculate about what would have occurred had Lincoln lived to sen’e out his second term. No doubt he would still be ranked high by presidential historians, who are always ready to be impressed by politicians who come out of desperate times on the winning side. Still, I suspect that the Lincoln of legend would not loom quite so large in our national imagination. In depriving us of the real Lincoln, who would have faced challenges in the next four years nearly as severe as those of the preceding term. Booth gave us the Lincoln who might have been. This figure is not the Old Testament God of the war years but a benevolent New Testament deity, who would have united us all—North and South, black and white—around the table of reconciliation and brotherhood. Thanks to Booth, we are able to believe that the wounds and bitterness that have plagued this nation since April 14, 1865, would never have existed had Lincoln only lived. Booth’s spectacular crime—committed on Good Friday, no less—can be treated as a kind of felix culpa, which has allowed us as a people to imagine so great a redeemer.

Curiously enough, Edgar Lee Masters himself created a fictive Booth seven decades before the publication of David Robertson’s novel. In his book of poems Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma (1930), Masters depicts Booth anticipating his final performance. In what is surely unintended irony, he declares:

God! If I die, send my mother

wordI died for my country. . . . Now I

mean to do.And do alone what armies could

not do.

[Lincoln, The Man, by Edgar Lee Masters (Columbia, South Carolina: Foundation for American Education) 498 pp., $29.95]

[Booth: A Novel, by David Robertson (New York: Anchor Books) 326 pp., $23.95]

Leave a Reply