“He fell with a thud to the ground and his armor

clattered around him.”

—Homer

War Music, called by its author, Christopher Logue, an “account” of four books of the Iliad of Homer, is not a minor event. Its reception both in its native England, and now here, has been enthusiastic. For, English writing, especially in verse, may not generally be said to have overcome its mortal challenge from the likes of Yeats, Eliot, and Pound, either to assimilate or displace, and Mr. Logue looks, at least here, like he means business. It is fair to say that—compared with the virtual armies of English-speaking poets of both sexes around the world who have developed drab ways of saying less than nothing but no will to stop saying it—Logue looms. He has a voice, he has technique, his audacity is immense, and he manages to say something.

Yet, it was impolitic on his part to label what he has done even an account—a maneuver intended to get him off the hook as a translator (mere or otherwise)—as War Music must simply be judged a new work. Now, I (for one) tend to like this sort of thing. Twenty-five years of rereading have not yet dimmed tire luster of Pound’s audacities with respect to Li Tai Po and Propertius, precursors to what Logue does here. But more than to Pound, Logue has apprenticed himself to the Chaucer and Shakespeare of Troilus (who both derive not so much from Homer as from the medievally extant “account” of Troy attributed to one Diktys, “of Crete,” a self-claimed eyewitness)—and even more than to any of these, to the Marlow of Tamburlane, Edward II, and Faustus. And, Peter Laurie is a poet and scholar whose work has appeared in Poetry, St. Andrews Review, and The Harvard Advocate. alas, more than to even these, to the whole modern medley of movies, TV, causes, tics, and ads.

If War Music must be denied its almost universal accorded encomium of authenticity with respect to Homer (and it must, for reasons I hope to touch upon, however briefly), nevertheless it remains all too true to this time. Mr. Logue and his well-wishers may feel this is all to the good, that they are satirizing modern life. If it were only that simple. Not knowing any more about Mr. Logue than this one volume tells me, I find his purposes murky, twisted, and self-defeating. But in the long war of the fashionable intelligentsia of the West against the West, this volume is a monument no serious reader can afford not to take seriously.

They call it Deconstruction, and it infests our higher life, using our universities as a base and oozing bogus revolution, conformism, pseudopacifism, revisionism, inversion, and incompetence, dedicated to convincing the immature and the unformed there is something better beyond the limits of traditional civilizations that traditional restraints (called “hypocrisies”) are blocking everyone’s way to, everyone’s right to. So the past is not taught but “tried” in the light of our superior understandings. The victims end by convicting not the past but their own soul—of revolting nullity. For there is, of course, something “beyond” civility, only it’s called savagery. In this race, I fear Achilles will never catch up with Mr. Logue.

Item: the willful transformation of Achilles and Patroclus into overt and active lovers—as Aeschylus did in the Myrmidons. The shrewd assumption is that for close on three millennia Homer has been hiding something only our superior powers of sleuthhood have found out. Unconsidered are the thousands upon thousands of living, ungay buddies who became and stayed fast friends from having withstood a barrage or taken a machine-gun nest side by side, or the physical demonstrations of affection among, specifically, Mediterranean men (even Mafiosi) who have never gotten it on. Moreover, Pythagoras, a source of ultimate authority who stands in the direct line of Homeric transmission (as a disciple of the Homerids, who passed the epic on orally), frequently cited just this relationship as an example of the higher philosophical dimensions of friendship because Achilles loved Patroclus as “another self” Let alone the mismotivation for Achilles’ grudge that ensues: If Briseis and Patroclus were both in bed with him, it would have been a war of a different color. In the Embassy scene of Book Nine, Patroclus and Achilles bed down with separate concubines. It’s implausible that the Homer who was frank about the one thing would hedge about the other. The Greeks were supreme authorities, it seems to me, on the subject of “greeking” (which Pythagoras forbade strictly as a form of blasphemy). The high place of the Iliad (and the Odyssey) in Pythagorean teaching is one major reason Homer (in Plato’s words) educated Greece. This high place of poetry in Greek culture is also one indispensable reason Greece has continued to educate us.

Which leads to—item: an obtrusive degree of invertedly eroticized combat, torture, murder, and corpse-pawing, as if Logue were trying to assert something about homosexuality as the universal cause of war:

1) Half-naked men hacked

slowly at each other

As the Greeks eased back the

Trojans.

They stood close;

Closer; thigh in thigh; mask

twisted over iron mask

Like kissing.

2) Achilles laved the flesh and

pinned the wounds

And dressed the yellow hair

and spread

Ointments from Thetis’ cave

on every mark

Of what Patroclus was, and

kissed his mouth

And wet his face with tears,

and kissed and kissed again . . .

3) Molo the Dancer from

Cymatriax tugs

At its penis as he squeaks:

“Achilles’ love!”

In setting out these three among dozens of such moments, gentle readers, it is not my purpose to take away what pleasure certain may find (have) in such passages, redolent of SS perverts, the pages of the Satyricon, and the interiors of certain private clubs, catering to sadomasochist imagination, in Mr. Logue’s fair city (London) and elsewhere. I merely wish, in view of reviewers’ misleading certitudes, to signal that such images are not the Iliad‘s—or anything like the Iliad‘s. Ditto:

And over it all,

As flies shift up and down a

haemorrhage alive with ants,

The captains in their iron

masks drift past each other.

Calling, calling, gathering light

on their breastplates;

So stained they think that they

are friends

And do not turn, do not salute,

or else salute their enemies.

. . . which is, though not Homer,

rather good, until:

But we who are under the

shields know

Our enemy marches at the

head of the column;

And yet we march!

The voice we obey is the voice

of the enemy.

Yet we obey!

And he who is forever talking

about enemies

Is himself the enemy!

. . . which collapses the momentary illusion of an ancient war into the deafening contemporaneity of a party line.

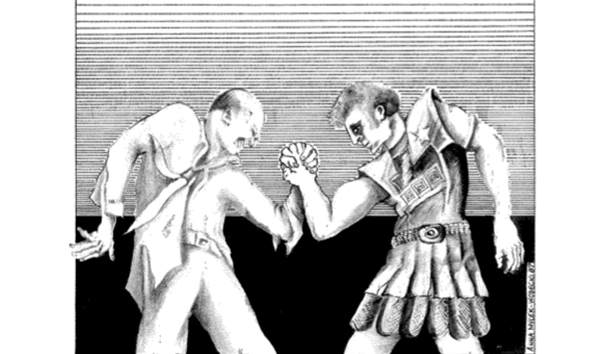

Mr. Logue gives voice and drama to that same cultish clutch of unexamined ideological assumptions that continues to paralyze contemporary will: that war is so awful it must not happen; that by crafting it in all its horror, the poet effects a change in human consciousness so it will never happen (never mind how many times it has before); that even a pervasive willful distortion of the qualities and motives of violence in accordance with the promptings of a mind I can only find deeply disturbed can, given our present backdrop of accredited victims seeking their own empowerment through emotional blackmail, pass for something as dignified as love for all mankind and a will to peace. I guess that, after all, is what the young black spear-chucker on the cover is meant to mean? Yet we affront not the pacifism of saints, the real kind, that wills to die before it kills, but rather the Saint Lenin variety (plugging one’s officer in the back)—the kind that brings its peace in total enslavement only when the last objecting man is dead. It brings to mind the apostles Burgess and Philby, all those brave Bloomsbury defenses of the Higher Buggery that blench before E.M. Forster’s immortal testament: “I hope when the time comes when I shall have to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friends, I shall have the guts to betray my country!” (That far-off ugly piercing sound is only Nietzsche cackling in his grave . . . )

For the revaluing of all values has now assuredly come into its awful own: that there is something almost universally admirable about self-proclaimed corruptions, that there is something correspondingly contemptible about any aspiration to traditional strengths of character, these latter reflexively stigmatized as “pretensions”—never virtues or ideals—whereas the former figure among the highest reaches of our latest version of honesty. If only Mr. Logue had thought himself back into Homer’s world, he might have come upon those very higher dimensions of being that alone might save us from our present selves: proper standards of manliness, honor, perseverence, priorities, duties, the imperatives forward and back of one’s line, the inspiration of eternal things, beauty and beatitude that must be earned in sorrows and in blood—that sort of thing.

Instead he chose to think their world forward:

And as she laid the moonlit

armour on the sand

It chimed;

And the sound that came

from it

Followed the light that came

from it.

Like sighing,

Saying,

Made in Heaven.

This, the scene in which Thetis presents Achilles with new arms and armor, is so much in the atmosphere of a TV commercial it might as well be about panty shields. “Made in Heaven” might better read “Made in Hong Kong.” Concourse with a divine, transcendant, permanent aspect of being—in which the heroes, their poet, his audience, all passionately believe—we can only relate to as cute kitsch.

Some of the battle scenes wouldn’t make the grade in Classic Comics:

And as the arrows start to

splash, back off,

Running towards the backslope,

up, a cat

Airborne a moment, one

glance back: “Dear God,

Their chariots will slice,”

splash, “corpse,” splash, splash,

“In half” . . .

Hera comes off as a gun moll:

” . . . If you stick

him, him, and him, I promise

you will get your Helen back.”

Helen is out of a Frederick’s of Hollywood catalog:

And Helen walks beneath a

burning tree.

Over her nearest arm her olive stole;

Beneath her see-through shift, her nudity;

A gelded cupidon depletes her woe.

. . . and is, of course (though the cupidon, lifted from the second part of The Waste Land, is originally “gilded,” not gelded), a castrating bitch, what else? Among many candidates, the fourth verse here may rank as the worst ever conceived by an English-speaking person not habitually employed in the greeting card industry.

Once, in Mr. Logue’s fair city (where the blurb gives to understand he also writes for film), a kindly elderly man named Henry James contemplated the work of a brash younger man named H.G. Wells and remarked, as of journalism in general, on the great new science of beating the sense out of words. Since, we have entered into the matter more thoroughly and can now beat the sense out of images (the stuff of the imagination, no less) themselves. So this “account,” which merely thrusts upon one of the world’s greatest surviving epics—one sovereign poetic heirloom of the dawn of Western civilization—its own deviant projections, does not even exist except for our time’s constructed capacity for the endless replication of solely manmade and man-manipulated images, images captured on film, stationary or moving, those hoaked-up pictures worth a thousand hoaked-up words, their “truth” a matter of who points the camera at what and why, validated by sales. It was not ever thus.

And if any ought to try to break the vicious cycle of this enslaving process wherein manufactured imagery gives birth to itself in logarithmic increase throughout every human mind (most atrociously the growing child’s mind) until it guarantees that even in one’s deepest dreams (dreams, which Plato called the language of the soul and of eternity) one communes not with one’s gods but the ubiquitous czars of trade—the poet should.

The epic poet prays to his muses, who are the daughters not of contrivance but of memory, to aid him in his projections of images of the real. His function is to sing what was, not make things up. Homer seems to have lived long after the events he describes with eyewitness precision, a precision so convincing it led Schliemann and Blegen to try to dig it all up, an enterprise of overwhelming success. Any discrepancies are merely plausible breakdowns in an oral transmission covering several centuries of transfer of the facts from bard to apprentice (the incorrect function of chariots, details of armament, the organization of the state, the so-called “wooden horse,” probably an imaginary explanation for a misunderstood siege engine, and so on). The forms of fantasy we have come to call “creativity” counted for very little (though there is some) in the formation of that classical temper of which the Iliad is our oldest and perhaps best exemplar. Consequently, the personalities Homer ascribes to the various putative historical characters in his poem are highly likely to be the personalities each of them actually had. What the poet supplies is Keats’s celebrated “negative capability”: He allows each in turn to fill his imagination, have his sympathies, and speak through the formular epic language of tradition. There is nothing pretty about Homer’s war, but at least wounds are only wounds, not occasions for gory fashion photography in verse. One fights over a dead hero’s corpse not to provide neat crosscutting but so that it may have the dignity of ritual burial that alone allows rest to the immortal soul.

Certainly that black warrior on War Music‘s cover looks like one to whom the original Iliad would make perfect sense. One hopes he never learns of the product his dignity has been pressed into making salable. (He looks like he would sure know what to do with Mr. Logue.)

And,

At a window of the closed

stone capital,

Helen wipes the sweat from

under her big breasts.

Aoi! . . . she is beautiful.

But there is something foul

about her, too.

This is the other of Mr. Logue’s borderline porn flick fantasies about a Mycenaean queen reknowned as the most desirable woman of all time. Surely The Real Thing would have known what to do about one such, too. I imagine her flicking her sweat in this poet’s voyeur eyes and drawing the curtain over the majesty and mystery of something arresting enough to be remembered by real poets forever.

[War Music: An Account of Books 16-19 of Homer’s Iliad, by Christopher Logue (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux) $12.95]

Leave a Reply