Dave Foreman grew up on a ranch in the mountains of New Mexico, where he came of age in the early 1960’s. Like many others of his generation, he joined the Young Republicans and campaigned for Barry Goldwater, witnessed the near-collapse of American society in the late 1960’s, and began to realize that the system he had believed in was out of whack.

Convinced that wild America ought to be preserved for the coming generations. Foreman became a conservationist, then a congressional lobbyist for the Wilderness Society. When it appeared that the nation’s leading environmental groups were paying more attention to fundraising dinners than to agitating for the preservation of wild places. Foreman fled Washington and, with other disaffected colleagues, founded Earth First!, a loosely knit alliance of environmental activists whose motto is “No Compromise in Defense of Mother Earth!”

The group took some of its cues and much of its anarchist agenda from the late Edward Abbey, whose novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, published in 1975, recounts the adventures of a group of ecosaboteurs who roam the West destroying dams and billboards. In spite of its cartoonish characters and transparent plot, Abbey’s book helped push radical environmentalism to the forefront of the ecopolitical movement in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, when Earth First! was founded.

In its decade under Foreman’s tutelage (it has no official leaders) the organization never numbered more than a few thousand people. Yet its members exhibited a special talent for outrageous publicity-garnering acts that gave Earth First! a presence much greater than its numbers would normally warrant: installing a plastic “crack” down the spillway of Glen Canyon Dam, sending a pirate ship afloat on the waters of Lake Powell in pursuit of visiting Interior Secretary James Watt, sabotaging bulldozers and performing in the dark of night “unauthorized maintenance on big yellow machines” and on other instruments of so-called progress.

Much of Foreman’s thinking derives from a rural, conservative, Luddite tradition. For his fiery speechmaking and endorsement of direct action, however, Dave Foreman was early on branded a dangerous terrorist by the federal government; the FBI set to work against him with the same zeal that it brought against the antiwar movement two decades ago, in the days before the United States learned to pick enemies who had no chance whatever of winning. Typically, the government overestimated the influence of Foreman’s organization. Earth First! people were harassed and local chapters infiltrated by agents provocateurs; in 1989, Foreman and three others were arrested on a charge of conspiracy to destroy a nuclear power plant near Phoenix, Arizona. The matter has yet to come to trial, but early reports suggest that the government’s evidence is slim at best. (The informant assigned to crack Foreman’s inner circle has admitted as much.)

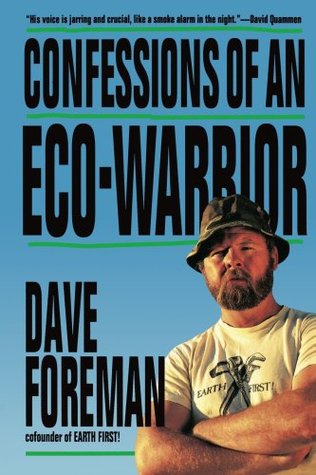

All this is enough to have made Dave Foreman something of a celebrity of the kind that generates instant, fast-buck autobiographies. Having appeared on 60 Minutes and the usual round of talk shows, in Confessions of an Eco-Warrior Foreman has obliged us with just a glimpse or two into his private life. “I’m not sure what this book is,” the author writes. “It’s not an autobiography or even a memoir. . . . It’s not a polemic or a how-to guide. I guess it’s a little bit like an ugly mongrel dog in which you can see the ears of one breed, the jowls of another, and so on.”

Like many other environmentalist authors. Foreman details the effects of the Industrial Age on our planet: the clearcutting of the world’s rain forests, the loss of biological diversity, the depletion of the ozone layer, the overgrazing of public lands. To alleviate these. Foreman proposes a radical program of action not much different from that of Earth First! (from which, its ranks now swelled with tie-dyed neohippies and cause-hoppers, he has lately resigned). He continues to urge the destruction of dams and the restoration of free-flowing rivers; the establishment of huge tracts of wilderness and roadless areas; and the practice of an idealized politics that admits of no compromise. Much of Confessions of an Eco-Warrior is an extended political pamphlet elaborating on these points.

In ten years’ time, Dave Foreman’s brand of radical environmentalism has served both to polarize the ecological movement and to push the rank and file toward greater activism. His program has as many detractors as it does followers, but few people within or without the environmentalist camp can simply shrug it off, and any serious ecological debate must somehow take Foreman’s positions, as elaborated in his book, into account.

[Confessions of an Eco-Warrior, by Dave Foreman (New York: Harmony Books) 229 pp., $20.00]

Leave a Reply