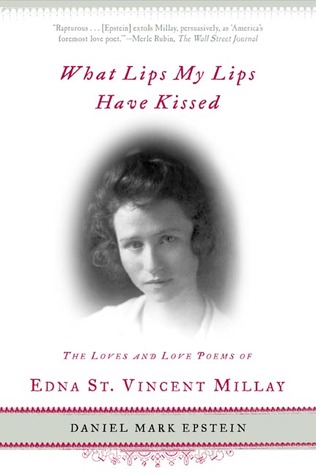

Like Virginia Woolf and Mary McCarthy, Rupert Brooke and Bruce Chatwin, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s striking appearance greatly enhanced her literary reputation. Readers were drawn to her poetry by her good looks and notorious sexual behavior. When she lost her health and beauty and became an alcoholic and a drug addict, she lost her following as well. After great pain came a greater pain. Millay (1892-1950), the most popular poet of her time, has fallen—like the painters Salvator Rosa and J.-B. Greuze, the composers Salieri and Meyerbeer, the writers Chatterton and Longfellow—into oblivion.

Daniel Mark Epstein, an enthusiast for Millay (in contrast to his ponderous rival biographer, Nancy Milford) narrates his story in a mercifully brief compass. He is good on Millay’s flamboyant lesbianism at Vassar, which evoked paeans to her “secret circles and folds”; her affair with writer Floyd Dell; her morphine habit and heavy drinking. She once passed out in a Pullman car and awoke, a few hours later, undressed and wondering whether the conductor had had his way with her. She died from falling drunkenly down the stairs and breaking her neck.

But Epstein, long on quotation and short on analysis, fails to substantiate the great claims he makes for her work. Her poetry lacks intellectual content, has mechanically predictable rhymes (fear-year, fall-call), and often descends into the romantic gush of an aging ingénue: “I am in love with him to whom a hyacinth is dearer / Than I shall ever be dear.” Epstein absurdly compares this stuff to the brilliantly complex poems of Donne, to the elegies of Milton and Shelley, to the visionary tradition from Blake to Rimbaud, to Pascal’s “geometry of belief” and Kierkegaard’s existential terror.

When you place Millay’s lines next to the truly great poetry from which they are derived, her mediocrity becomes obvious:

then you must speak

Of one that loved not wisely but too well [Shakespeare, Othello].

I had not come so running at the call

Of one who loves me little, if at all [Millay].

The grave’s a fine and private place,

But none, I think, do there embrace [Marvell, “To His Coy Mistress”].

And scarce the friendly voice or face,

A grave is such a quiet place [Millay].

Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:

England hath need of thee [Wordsworth, “London, 1802”].

You who have stood behind them to this hour,

move strong behind them now [Millay].

Do not go gentle into that good night . . .

Rage, rage against the dying of the light [Dylan Thomas, “Do Not Go Gentle”].

I am not willing you should go

Into the earth where Helen went [Millay].

Epstein calls The King’s Henchman, an obscure and now forgotten work on which Millay collaborated, “an important event in the history of opera.” And, claiming Millay’s love letters “rival the greatest love letters of all time,” he quotes the bogus Keatsian line: “an enchanted sickness comes over me as if I had drunk a witch’s philtre.”

Epstein, himself a poet, frequently lapses into cliché: “The letters from Camden came fast and furious. . . . Her mother and sisters were frantic without her, could not understand why on earth they had heard nothing from her.” He is extremely repetitious, mentioning at least a dozen times that Millay had red hair. He also offers many trivial and boring details while neglecting a number of crucial points: the beliefs of Millay’s Congregational Church, her friendships with the poet-suicide Sara Teasdale and composer Deems Taylor. He dismisses her round-the-world trip in two sentences (names of ports will not do) but spends half a page on the clothes she wore during a poetry reading.

Everyone in Millay’s circle, except Edmund Wilson, was third rate, and it is difficult to get excited by poet-lovers like George Dillon and Arthur Davison Ficke (beware of authors with three names). Epstein tries desperately to inflate these people. The mediocre Claude McKay is “the great black poet.” And Witter Bynner—whom D.H. Lawrence satirized in The Plumed Serpent as Owen Rhys (“so empty, and waiting for circumstance to fill him up. Swept with an American despair of having lived in vain, or of not having really lived”)—is “one of the most gifted poets of his generation.” Epstein also makes some notable blunders. He calls Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, rather than The Rainbow, “scandalous,” and substitutes “frozen field” for “foreign field” when misquoting the famous lines of Rupert Brooke.

Epstein also fails to explain the complex dynamics of Millay’s fascinating sex life. As with Dora Carrington, the elusive bisexual siren of the Bloomsbury Group, it is difficult to see, from photos and descriptions by men who adored her, the extraordinary physical attractiveness of this tiny, skinny woman. Pale, freckled, flat-chested, and chinless, Millay was certainly not beautiful. But she was androgynous, very sexy, and—with 100 certified lovers—always available, responsive, and willing, indeed eager, to sleep with any man who struck her fancy or was able to advance her career. (Editors were her specialty.) Men never had time to seduce Millay, who would ravish them before they got the chance.

On July 18, 1923, Edna married the eager-to-be-cuckolded Eugene Boissevain on the very day she had a major operation for intestinal adhesions. Ficke became a neighbor, and Millay, with Eugene’s active encouragement, continued her promiscuous affairs. He seems to have achieved sexual excitement and covert homosexual pleasure (rather than jealousy) by sharing his wife with other men.

I came away from this interesting but disappointing book with quite a different impression of Millay than Epstein intended to convey. Manipulative and selfish, cynical and callous, reckless and destructive, Millay—always the sexual predator—had a pathological desire for “fresh wreckage.” If you are not enthralled by her charms, the poetry fails.

[What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay, by Daniel Mark Epstein (New York: Henry Holt) 300 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply