Mark Steyn is the only neoconservative who can still make you laugh. David Brooks could, when he and I worked at the Washington Times in the mid-1980’s; he was great with the jokes in person and in writing. But after Brooks was hired at the New York Times in 2003, he took on the High Seriousness that afflicts the paper. The other neocons are dullards all.

Steyn’s main stylistic fault is that he doesn’t let up with the levity. Maybe that’s OK in a column. But in a 424-page book, I kept muttering, like Gertrude to Polonius, “More matter, with less art.” I enjoyed Steyn when I started reading his syndicated column in the late 1990’s. In 2000, he wrote a column about attending a breakfast featuring George W. Bush, then running the soft gauntlet of Republican primaries. Steyn gushed so much about Bush that I thought, I’m not going to enjoy his writing if Bush wins. That came true with Bush’s election and became worse after the September 11 attacks. Steyn, a Canadian educated in England, raved for his liege lord like a royal courtier. The Afghanistan and Iraq wars made him a Colonel Blimp imperialist cheerleader, though he never served in the military. He became unreadable.

Steyn’s first book was America Alone: The End of the World (2006), in which he insisted that civilization had collapsed in Western Europe, and only America remained as a beacon of hope. Both Steyn books are neocon variations on such Pat Buchanan titles as The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country (2002) and State of Emergency: The Third World Invasion and Conquest of America (2006). The main difference between the two authors is that Buchanan correctly identifies the great costs of America’s recent wars as a major factor in the country’s financial demise, while pointing secondarily to the expense of the welfare state. Steyn, by contrast, puts the welfare state first. But surely Buchanan is right. He is also, actually, less alarmist.

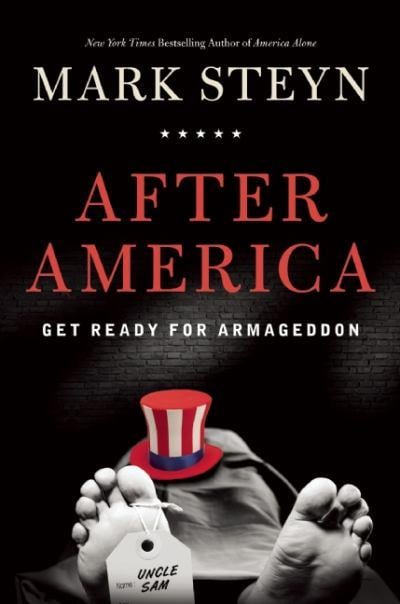

Is there really, as Steyn’s new book has it, an “after America”? Despite her decline in recent decades, America is still here, and likely will be for decades longer. Hilaire Belloc pointed out that it is virtually impossible to destroy a large country completely. An impending financial collapse of the type Steyn warns against might actually have a positive effect by forcing the return of troops from abroad and the reduction of the meddling welfare state. And are we really facing “Armageddon”? Only Russia and China can hit us with ICBMs, an event less likely to happen today than during the Cold War. A plague also seems improbable. The book’s cover carries a picture of the corpse of Uncle Sam in a morgue with a toe tag depending from it—a trope for the U.S. government, which, however, is bigger and meaner than ever.

Buchanan is right also in claiming that protracted wars and the welfare state have expanded together. They go together like a horse and a cannon. World War I brought the first major federal involvement in medical care, which led eventually to ObamaCare. Doris Kearns Goodwin’s No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II is an encomium to the Roosevelts’ project to use the war as a lever to advance social changes. Jeffrey Helsing’s book Johnson’s War/Johnson’s Great Society: The Guns and Butter Trap describes how LBJ combined war and welfare. Similarly, Steyn’s hero George W. Bush bound war together with a vast expansion of federal control over education and the expansion of Medicare under “Plan B” that added three trillion dollars to the national debt. Bush’s Iraq war by itself exploded the debt by five trillion dollars, according to economist George Stiglitz, if the costs of servicing the debt and caring for wounded veterans are included, while the Afghan war has cost at least one trillion dollars. In short, Bush ran up the debt by as much as nine trillion dollars. The six trillion dollars in new debt accumulated by President Obama, which Steyn decries, is just piling on.

Steyn is rightly critical of the excesses of Muslim fanaticism, especially the removal of Christians from many countries:

In 2003 President’ Bush’s “coalition of the willing” took Baghdad from Saddam Hussein. There were at that time an estimated million or so Christians in Iraq. By 2010, their numbers had fallen by half. . . . This happened on America’s watch—while Iraq was a protectorate of the global hyperpower.

In fact, by 2010 America had been revealed as a global paper tiger, unable to transform its gargantuan Cold War military-industrial complex into a nimble Fourth Generation War operation, as William Lind and others have described. Although hunting down Osama bin Laden was a worthy effort, the expensive diversions involved in attempting to turn Iraq and Afghanistan into model democracies delayed his demise by eight years.

As Lind has pointed out, the first rule of Fourth Generation War—basically, nonstate war—is to avoid involvement in foolish wars such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan. The second is not to smash up states, whose destruction produces uncontrollable insurgencies like those in Iraq and Afghanistan—and in Libya, Somalia, and Yemen.

As for the Christians expelled by the Muslims, Steyn fails to note that on September 16, 2001, days after the attack on the World Trade Center, President Bush announced that “This crusade, this war on terrorism, is going to take a while.” Most Americans think a crusade is Billy Graham in a stadium. But Muslims in the Middle East still resent the Christian crusades that began nearly a millennium ago. And in Iraq, extremists immediately turned on Christians who, after living in a semblance of peace with the dominant Muslims for 1,300 years, were suddenly branded allies of the new “crusaders.” It was, in short, the invasion conceived and promoted by neoconservatives like George Bush and Mark Steyn that proved the catalyst for the Christians’ exodus.

Steyn does understand that war has changed, to some small degree at least. Here is his pop imitation of Clausewitz:

So, in the fall of 2001, the Jetsons toppled the Flintstones. And the Flintstones bided their time, and quickly figured out that the Jetsons didn’t have the stomach to do what it takes, and their space-age occupation of Bedrock would rapidly dwindle down into a thankless semi-colonial policing operation for which the citizenry back on the home front in Orbit City would have no appetite.

But to “have the stomach to do what it takes” would mean drafting millions of young men—and women—into the Armed Forces and sending them to butcher perhaps half of the Afghans and Iraqis to cow the rest into submission. That’s how the Mongols did it. That’s how Stalin took care of the Chechens in the 1940’s, and how Putin dealt with them again in the 2000’s.

Unlike most neocons, Steyn understands that recent immigration has been a disaster for America. He quotes, for instance, Bertolt Brecht’s now-familiar question, “Would it not be easier for the government to dissolve the people and elect a new one?” Steyn’s book was published shortly before the recent election, which provided still more proof of just that happening, as the racialists in the Democratic Party and the plutocrats among the Republicans pounded the old American majority into minority status yet again.

“The easiest way to elect a new people is to import them,” Steyn writes.

So the Eloi not only turn a blind eye to mass “undocumented” immigration, but facilitate it, and use the beleaguered productive class to subsidize it. Grade schools are not allowed to ask parents if they’re in the country legally. . . . Across America, school district taxpayers are funding the subversion of their own communities. . . . Almost every claim made for the benefits of mass immigration is false.

And why is this happening?

Because the governing class decided, with the 1965 immigration act and much that has followed, that that’s the way it’s going to be. In the not entirely likely event that the GOP could persuade Hispanics to vote in overwhelming numbers for small government, the Democrats would look elsewhere for new clients—Muslims, say, maybe from Somalia, a nation which, in barely more than a decade, has transformed the welfare profile even of such backwaters as Lewiston-Auburn, Maine.

The final chapter, “The Hope of Audacity,” is an unfortunate spin on Obama’s The Audacity of Hope. Here Steyn calls for reforms, all of which begin infelicitously with the letter d: de-centralize, de-governmentalize, de-regulate, de-monopolize, de-complicate, de-credentialize, dis-entitle, de-normalize. This has been conservative boilerplate since the presidential election of 1964. It’s also a pretty lame way to “Get Ready for Armageddon.” How about stocking up on ammo, MREs, and other survivalist supplies?

Unlike most neocons, Steyn seems to be evolving toward a more realistic conservatism: He actually approves of “the old, free America,” as Kenneth Rexroth called it. Steyn needs now to surmount his fixation with war. He should talk to people like my neighbors, who lost a son to an IED in Iraq in 2006. Or visit a veterans’ hospital and chat with the GIs who have spinal injuries about their former girlfriends. We’re not “after America.” We just need to fix the America we have.

Leave a Reply