When it comes to social hierarchy, smokers are only a few notches above pedophiles. Yes, smokers are bad, they smell terrible, and they cost us money—and everyone knows it.

One would expect the “smokers bad” message to saturate The Cigarette. Surprisingly, author Sarah Milov spends almost no time singling smokers out for abuse. On the other hand, the book includes the requisite virtue signaling throughout to remind us that just like cigarettes, the elite, privileged white patriarchy is bad, too.

Now if your idea of a history of the cigarette involves a deep dive into how tobacco was farmed, how cigarettes were manufactured, why people started smoking, the various marketing pushes over the decades, a concise timeline of key moments, how smoking was perceived in different decades, changing smoker preferences, and other similar interests, then The Cigarette will probably disappoint. On the other hand, if you enjoy meandering through the dense history of New Deal tobacco subsidies, surgeon general reports, anti-smoking activism, and the changing fate of the tobacco industry, all backed up by 964 footnotes, then this book is for you.

Those footnotes jumped out almost immediately, with 56 of them in the introduction alone. As a result of the pervasive footnoting, The Cigarette at times resembles an undergraduate essay, cobbled together through a repeating pattern of sources, quotations, and commentary that are not always clearly connected. It makes for a tedious read.

Milov obviously went to great lengths to research the history of the cigarette. It’s overwhelmingly evident as the book brings to light hundreds of fascinating points, getting into many details that would likely be entirely new to the reader. Nonetheless, the structure and organization of the book is frustrating. Rather than research, step back, reflect, and then tell a concise story of the cigarette as she conceived it, Milov seems to allow her research to dictate the flow of the book, causing it to feel jumbled and repetitive.

Virtue signaling appears regularly with “whiteness,” “white elites,” “racist,” “patriarchal,” etc., sprinkled about, but it seems mostly superfluous and is contradicted by the book’s own data. With no central theme blaming cigarettes on “whiteness” or some other social justice catchword, a discerning reader can gloss over the virtue signaling.

More of Milov’s ideological bias comes through as she describes important individuals and programs. For instance, New Dealer Rex Tugwell is described as a “broad-minded heterodox economist.” Later in the book, Alger Hiss is described as a “liberal” with no mention of his crimes, while in the same sentence former South Carolina senator James Byrne is referred to as “arch-conservative.” Of course, if Alger Hiss is mentioned and described as a “liberal,” you would expect Milov to take a swipe at Senator Joseph McCarthy. And you would be correct. Milov describes “McCarthyite censorship” as the “fervid heyday of Hollywood red baiting.” The gratuitous point had absolutely nothing to do with the history of the cigarette. Other examples of the author’s bias are plentiful. Much like the virtue signaling mentioned already, the bias is annoying, but not a central theme laying the blame for cigarettes on a particular ideology or people.

Setting those critiques aside, Milov is thorough in her history of the cigarette. She starts the story with the advent of the cigarette itself as a new competitor to pipes and cigars in the late-1800s. Prior to World War I, the cigarette was largely frowned upon by the cultural elite. Cigarettes were commonly referred to as “little white slavers.” In his pamphlet The Case Against the Little White Slaver, published between 1914 and 1916, Henry Ford went so far as to state that he would not hire a smoker and that he believed “men who do not smoke cigarettes or frequent the saloon can make better automobiles than those that do.” Prior to 1900, the author claims “most Americans did not consume any form of tobacco.”

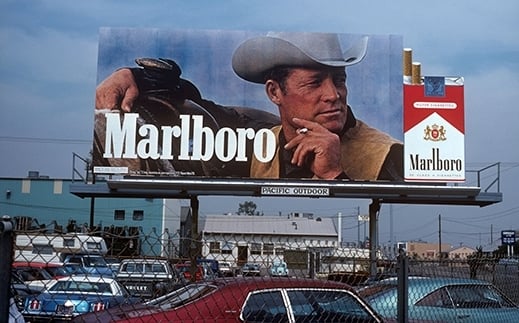

Milov believes three things changed Americans’ perspective on cigarettes: immigrants, war, and advertising. If you thought the Marlboro Man is rooted in history, he is not. It turns out that the real smokers in the early 20th-century West were Europeans. The popularity of smoking cigarettes in America grew modestly only as immigration grew, and that was concentrated in the big cities, not on the range. It was World War I that quickly improved the cigarette industry’s financial position as cigarettes became a key item for soldiers. General John J. Pershing “regarded cigarettes as being as vital a necessity as food—‘tobacco as much as bullets.’”

When the soldiers came home from abroad, they brought back new perspectives and changed habits, particularly regarding smoking. With this significantly broadened base of support, the cigarette industry then poured on the advertising after World War I to change the image of cigarettes and increase their popularity. Prior to WWI, Milov points out that men smoking cigarettes were considered effete. After WWI, tobacco advertising created the image of smokers as rugged, sophisticated individuals. Perhaps the industry’s greatest coup occurred in the 1920s when advertising convinced women that they, too, could and should be smokers.

Despite the cigarette’s growth in popularity in the 1920s, there were fundamental financial problems in the tobacco industry, particularly for the small farmers supplying the tobacco. The Great Crash of 1929 exposed all of the industry’s weaknesses, especially the amount of debt many farmers were unsuccessfully carrying forward. According to the analysis of the New Dealers, prices were too low and production was too high, throwing many farmers into bankruptcy. Meanwhile the cigarette manufacturers were swimming in money. Pithily, Milov writes of the era, “Cigarettes, it seems, were depression-proof. Tobacco was not.”

The New Dealers rescued tobacco farmers and enabled the tobacco industry with price support programs that lasted until the 1980s and that decade’s push for deregulation and anti-smoking initiatives. Most of the book focuses on those New Deal programs, the rise of both anti-smoking and deregulation crusaders, the change in public opinion, and the eventual deconstruction of the tobacco support programs.

The first significant improvement for tobacco farmers came from the Agriculture Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933. To benefit tobacco farmers and keep them from losing their farms, a partnership of government, industry, and farmer associations pulled together to use the federal government, empowered by the AAA, to actively reduce the supply of tobacco through quotas; implement tobacco importation restrictions; and pay farmers to not produce. Furthermore, the government set about to fix the domestic price of tobacco, though not cigarettes, while expanding the market for them internationally.

Free marketeers will denounce such a public-private incursion into market forces, but there can be no doubt it was beneficial to tobacco farmers and allowed for the preservation of the small family farm for many decades. According to Milov’s research, on the macro level the program was a stunning success:

Compulsory agricultural adjustment brought prosperity to tobacco producers. For the first three years of the AAA’s operation, flue-cured [tobacco] farmers netted more cash with each year: $182 million in 1933-1934; $229 million in 1934-1935; $247 million in 1935-1936.

The benefits of the program, despite Milov’s many references to white elites orchestrating it just for themselves, went all the way down the tobacco industry hierarchy. As Milov shares, “A black farmer who had netted $11.30 for five acres of tobacco in 1932 earned $1,472 in 1934—despite a cut in his acreage.”

The downfall of tobacco began with the 1964 release of the Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health, which “concluded that cigarettes caused death,” knowledge taken for granted in our times. From that year on, Milov details the multi-pronged and largely grassroots activism deployed for decades to eradicate smoking from public spaces and lower the overall rates of smoking.

While nonsmokers may have disliked sitting in smoky public venues such as restaurants, offices, and planes, up until the report’s release they didn’t have the evidence to show it was potentially deadly. Now with evidence in hand, anti-smokers began their long march to eradicate smoking under the banner of “nonsmoker rights,” playing off the civil rights movement of the same period.

The nonsmoker rights strategists believed they couldn’t get change through Congress because the tobacco industry, representing thousands upon thousands of tobacco farmers and the wealthy cigarette manufacturers, had an iron grip on the legislative body. Instead, these activists pursued two strategies: get government agencies and the courts to change laws at the federal or state level, and then use activism to do it on the local level.

The details Milov provides about the nonsmoker rights activists give the reader a blueprint for the Left’s relentless push for incremental change over the last sixty years. One of the founders of the anti-smoking movement, George Washington University Professor of Law John Banzhaf, taught “anti-establishment law,” including how law should be used as “a weapon against major social problems,” through his legal activism course nicknamed “Sue the Bastards,” which essentially sums up the effort.

The activists made modest legal progress banning smoking in various public settings, but Milov’s research indicates the tipping point for the anti-smoking crusade occurred due to changes in business philosophy on smoking. Prior to the 1970s, many businesses, if not most, allowed employees to smoke indoors. Anti-smoking activists smartly concentrated their efforts on convincing businesses that smokers were less productive and cost a company more money than nonsmokers. They were extremely successful even before the release of studies showing the danger of second-hand smoke.

As businesses began prohibiting smoking indoors and some even made efforts not to hire smokers, the anti-smoking movement picked up momentum and became a juggernaut, pushing smoking out of one public space after another from the mid-1970s on. Alongside the change in business philosophy came a change in how politicians and others viewed the New Deal programs, particularly the tobacco program. Many on the right, and even on the left, sought deregulation, effectively the deconstruction of the New Deal, in the late-1970s and 1980s.

Tobacco farmers were already hurting financially from various program changes, particularly the ability of cigarette manufacturers to import tobacco from countries with cheaper labor rates. These changes financially gutted the small farmers while enabling the cigarette manufacturers to reap major profits despite the growing disdain for cigarettes and smoking:

Between 1980 and 1984, tobacco enjoyed a return on investment of more than 20 percent—more than double the return in the rest of the corporate world.

As corporate profits swelled, farmers faced slimmer margins. During the 1980s, price supports were frozen and then lowered, and quotas were slashed as imports continued unabated. The exodus of small tobacco producers from farming was a quiet chapter during a decade of farm crisis that saw the dramatic foreclosure of thousands of Midwestern farms. The nationwide trend of farm consolidation and capital-intensive production played out in the tobacco region in miniature.

While The Cigarette was a chore to read, there were a couple themes that stood out most: tariffs and corporate activism. With foreign competition limited, though aided by a government-sponsored lending and price system, American tobacco farmers did quite well. Once the anti-smoking activists convinced corporations to not only ban smoking but to actively join the campaign, a tipping point was reached. Against corporate activism and the reduction of tariffs, the small-time tobacco farmer didn’t stand a chance.

[The Cigarette: A Political History by Sarah Milov (Harvard University Press) 400 pp., $35]

Image Credit: above: Marlboro Cigarettes billboard in Los Angeles, CA circa 1976 (Robert Landau / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply