The lives of great men are largely unconstrained, which may explain why there are so few great men today. All men are, of course, constrained by their personal limitations as well as by the limitations their age imposes on them, but it is in the nature of greatness to overcome such limitations to the extent that they can be overcome. Nevertheless, certain periods of history are more amenable to greatness than others; usually, these others are conducive more to the flourishing of what Evelyn Waugh called the Common Man (at least insofar as the Common Man understands flourishing) than to that of the Uncommon, who is constrained precisely to the extent that the Common Man is unbound.

The second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th scarcely appeared as a golden age in Western European civilization. Still, there is degree in all things; and a civilization that not only produced such a man as Hilaire Belloc but permitted him to flourish (though not financially) has a lot to be said for it (though Belloc himself might not have agreed). He was a man of fluid personality to match his mercurial temperament, and this fluidity extended to his amorphous and unpredictable career. In a more systematized and sclerotic society like our own, in which success requires that everyone be more or less identified with a single product or activity—in effect, to be his own brand name—Belloc would more likely have had a disastrous career.

Today, such a man—who took a First in History at Balliol; was elected president of the Oxford Union; underwent military training in France (of which he was, at the time, a citizen); wrote several successful volumes of cautionary verse for children and also works of “serious” poetry; walked from Paris to Rome and made a book from the journey; bought an old nine-ton cutter to sail the coast of England and made a book of that; stood for Parliament on the Liberal Party ticket, was elected, and once returned; openly opposed in Parliament the party he represented; earned a reputation as a radical politician, a Distributist, and an orthodox Catholic apologist; contributed a weekly magazine article on the military situation as it developed during World War I; and devoted most of the rest of his life to writing history—would be considered, from a marketing standpoint, quite unmanageable, if not unemployable. It is a credit to the country that adopted him—or he, it—that Hilaire Belloc stands today as one of the great writers produced by the England of Lloyd George and Wells, in progress toward that of Princess Di and Tony Blair.

Perhaps Belloc’s success as a writer and public figure was ultimately made possible by the toleration still extended in his lifetime to striking personalities and unorthodox opinions. In Hilaire Belloc’s case, of course, heterodoxy was determined for him by his faith—or, at least, by the way in which he understood that faith.

Belloc was born at La Celle St Cloud, outside Paris, to a French father who

had married an English convert. He was reared on both sides of the Channel but received his education in England. As

a young man, he was powerfully influenced by his mother’s great friend, Henry Edward Cardinal Manning—an ultramontanist and an advocate for the poor and the working classes—who taught him that all human conflict is, at bottom, theological. (Belloc would later refer to “a dogmatic assertion of truth.”) Belloc’s birth in July 1870 coincided poetically with the culmination of the First Vatican Council’s declaration of the dogma of papal infallibility.

Belloc took pride in his French lineage; his paternal grandfather, a well known painter, especially. As a youth, he developed a sympathetic interest in the French Revolution, and the subject of his first book is Danton. At the age of ten, he was accepted at the Oratory School near Birmingham, whose master was John Henry Cardinal Newman, also his mother’s friend. And Belloc was only 21 when Pope Leo XIII issued Rerum novarum, his encyclical addressing social and economic injustice in the modern industrial world, which was to inspire his own and Chester-ton’s distributist creed in the next century. In his life of Belloc, Joseph Pearce writes,

For the impressionable youth, whose own background was rooted in the philosophy of the Church and in the politics of the French Revolution, the combination of traditionalism and radicalism that Manning preached was a potent one.

It was so potent (and satisfying) a combination, indeed, that it satisfied Hilaire Belloc to the end of his 83 years.

Already in his Oxford days, Belloc, as president of the Union, was engaged in what Pearce describes as “cutting through the cant of left and right and countering it with a beguiling combination of radicalism and libertarianism.” And he was getting away with it, and even making a name for himself—becoming a celebrity, in fact. That is what is known as civilization. In today’s postcivilized world, controlled and constrained by a tightly wired and closely monitored system devised by the power-mad, the money-mad, the fanatical truth deniers, the professional liars, and their sycophants, a man’s views are supposed to be all one thing or the other.

We in the West are living through a Cold Civil War in which everyone is expected to take his side and stick with it, dedicate his pen to propaganda, his mind to pabulum, and his life—private as well as public—to conformity. Anyone who does not choose his side is rejected by both and becomes not only a ridiculous figure—doing his St. Vitus Dance on the open ground between the opposing lines—

but an easy target for the special amusement of the opposed rif lemen. Owing to his genius, his resiliency, and his determination, Belloc would almost certainly have survived in such circumstances, and made his voice heard, if not prevail. This, after all, was the man who advised a packed political meeting in South Salford that, “If you reject [my candidacy] on account of my religion, I shall thank God that He has spared me the indignity of being your representative” (a statement that was answered, after a stunned silence, by a crash of applause). He would not, however, have received telegrams of congratulation on his 80th birthday from the likes of Mr. and Mrs. Churchill, nor have been featured on a radio broadcast of the BBC. Probably even the present archbishop of York (whoever he may be) would have ignored the event as well—since this, too, was the man who inveighed against the unparliamentary nature of parliamentary “democracy,” complained during his own parliamentary career that “[The House of Commons] does not govern; it does not even discuss. It is plainly futile,” and, after standing down from his seat, promised that, “when realities . . . enter politics . . . I shall re-enter politics with them.”

It is a commonplace today in certain circles (i.e., the losing ones) to hear people remark that, after all, living well and having fun are the best revenge. Things in Belloc’s own time were not yet so grim for people of his type. Nevertheless, Belloc lived as if he thought they were, and he was determined to take his revenge by living the fullest life possible. Though he wrote over a hundred books and thousands of articles, Hilaire Belloc never resembled the driven careerist, the stoop-shouldered scholar locked away in his study, the pale and pasty Gradgrind bent over his desk. He was a strong and vigorous man, though inclined to corpulence in middle age as a result of an appetite equally vigorous for food, wine, and ale as for the manly activities of canoeing, sailing, yachting, tramping, horseback riding, and doing his own brick and stone-work at King’s Land. The “boozy halo” surrounding his and Chesterton’s friendship (which produced the lumbering literary beast George Bernard Shaw dubbed the “Chesterbelloc”) was legendary in their time, giving rise inevitably to such witticisms as “The Man Who Was Thirsty.” Chesterton himself claimed that Belloc’s “low spirits were and are much more uproarious and enlivening than anybody else’s high spirits.”

A typical evening with Hilaire Belloc included torrential conversation (never spoiled by pontification), red wine flowing, and Belloc singing his own songs in a voice that Max Beerbohm once compared (for Edmund Wilson’s benefit) to that of “a very large nightingale.” Even after the pre-mature death of his beloved wife, Elodie Hogan (a California girl), when both were in their 40’s, though the tragedy marked him forever and he never remarried, Belloc maintained that gusto that was a special property of his genius, manifesting itself in his work as well as in his life.

At the bottom of this joie de vivre was, of course, the Faith with which his name is identified. Belloc was irrepressible because he never repressed his powerful instinct for life, which was at bottom a religious impulse. Visitors to King’s Land were likely to be summoned out into the night to “watch God make energy” in the sky, or treated to a peculiar family ritual round the dinner table, initiated by one child suddenly shouting out “Hell!”—whereupon all the Bellocs fell to clashing their knives against their plates to simulate the souls of the damned gnashing their teeth in Hades. It was faith in Heaven that gave Hilaire Belloc, when he needed it, faith in himself. Not quite 20, he was persuaded by Elodie not to make a defiant stand for election to the vacant professorship of history at Glasgow University, whose principal had informed the young man (who, as an historian, was in maturity to insist that Europe is the Faith and the Faith, Europe) that his religion was an absolute bar to the post. Belloc wrote to a friend,

It is very sad . . . I have fits of depression when I consider that there is no future for me, but I am merry when I consider the folly, wickedness and immense complexity of the world. It is borne in upon me that before I die I shall write a play or a poem or a novel, for the sense of comedy grows in me daily.

There was, of course, another, less sensitive and more classical side to Belloc’s makeup that was perceived by Chesterton at their first meeting: “What he brought into our dream was his Roman appetite for reality and for reason in action, and when he came to the door there entered with him the smell of danger.”

All literature begins with poetry, and poetry has its beginnings in the recitation of the lives and deeds of great men, in whose countenances we see the face of the poet-biographer reflected, however faintly, if he is worthy of his subject. Having read Old Thunder, I know Hilaire Belloc much better than I did before, while suspecting I might recognize Joseph Pearce himself from among a congeries of faces across a crowded room.

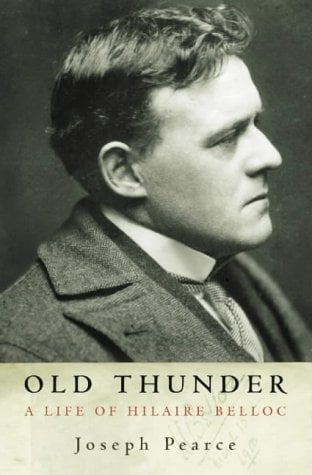

[Old Thunder: A Life of Hilaire Belloc, by Joseph Pearce (San Francisco: Ignatius Press) 318 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply