Southerners have a special feeling for the pathos of history. They know what it is like to have a lost cause, a history that might be gone with the wind but is still resonant and noble for all that. The Southern Confederacy’s almost-allies, the British, also have a sense of the pathos of history. But where the South’s has come from defeat in war, Britain’s has come from victory—a case of winner take nothing.

In his latest book, just published in England, George MacDonald Fraser writes with the bracing honesty of a former infantryman who wants the truth to be remembered and not swallowed in the memory-hole created by purveyors of political correctness. The book begins, “The first time I smelt Jap was in a dry-river bed. . . .” Smelt. Jap. Oh dear. George MacDonald Fraser is someone for whom the truth isn’t a political plaything; it is what he saw, heard, experienced, and . . . smelt. He doesn’t intend to eater to the prejudices of the young or the ideological, and he’s in no mood to apologize for himself or his fellow soldiers. For him the truth is merely true. That makes him a dangerous, but entertaining, fellow.

For those not familiar with his literary corpus, George MacDonald Fraser is the author of the joyous Flashman novels chronicling the robust rovings of a rogue of an English officer in Queen Victoria’s Empire, an accomplished writer of humorous short stories describing life in a Scottish regiment and its disgraceful Private McAuslan, and the cheeky screenwriter of such movies as The Three Musketeers, The Four Musketeers, and Octopussy.

Quartered Safe Out Here is the true story of Eraser’s own service as a 19-year-old infantryman in the 17th Black Cat Division of General Slim’s 14th Army; the story of brave, swearing old sweats, grumbling and fighting their way through the heat, the rain, the snakes, the leeches, the mosquitos, and the Japs. It was a good war for Fraser, and he is proud of his service in what he reckons—with its Gurkhas, Africans, and Indians—was the most multinational army since the time of Rome, and one just about as experienced at keeping the imperial peace. When George MacDonald Fraser went to war in Burma, he wore the ring of his great-uncle, buried in Afghanistan, who had gone to war under General Roberts. His grandmother greeted Chamberlain’s declaration of war with a simple sigh: “Well, the men will be going away again,” as they had gone away and died in the Crimea, in all parts of the tropics, and on the Western front in France.

Near the end of Quartered Safe Out Here, Fraser makes a case—like most servicemen who risked their lives on the blood-soaked beachheads of the Pacific and in the malarial swamps of the Far East to defeat Imperial Japan—in favor of America’s dropping of the atom bomb on Nippon. But he also imagines what the result would have been if his own section—a rough but steady lot of tough Cumbrian borderers with a natural talent for scrounging their way through life—had been told that the war could end either immediately with the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki or more slowly through an indefinite continuation of the slogging warfare that had occupied them for the last six years in monsoon-drenched jungles against an enemy that preferred a banzai charge to surrender:

They would have cried, “Aw, fook that!” with one voice, and then would have sat about, snarling, and lapsed into silence, and then someone would have said heavily, “Aye, weel,” and got to his feet, and been asked, “Weer th’ ‘ell you gan, then?” and given no reply, and at last the rest would have got up, too, gathering their gear with moaning and foul language and ill-tempered harking back to the long dirty bloody miles from Imphal boxes to the Sittang Bend and the iniquity of having to do it again, slinging their rifles and bickering about who was to go on point, and “Ah’s aboot ‘ed it, me!” and “You, ye bugger, we’re knackered afower you start, you!” and “We’ll a’ get killed!” and then they would have been moving south [to fight the Japanese in Malava]. Because that is the kind of men they were. And that is why I have written this book.

They were not the sort of men who, as Fraser points out, would have needed “‘counselling’ on how to ‘relate’ to members of the opposite sex after a few months in the desert,” as American troops required in the Persian Gulf War.

Indeed, Fraser does an excellent job of garroting the modern idiocy of “sensitivity” and “counselling.” And he, though an old newspaperman himself, has harsh words for an overly inquisitive media obscenely poking their microphones in the faces of war-weary grunts, straining to find “post-traumatic stress” among every Tom, Dick, and Harry. As Eraser notes, “One wonders how Londoners survived the Blitz without the interference of unqualified, jargonmumbling ‘counsellors’. . . . Fortunately for the world, mv generation didn’t suffer from spiritual hypochondria—but then, we couldn’t afford it. By modern standards, I’m sure we, like the whole population who endured the war, were ripe for counselling, but we were lucky; there were no counsellors. I can regret, though, that there were no modern television ‘journalists,’ transported back in time, to ask Grandarse [a member of his section]: ‘How did you feel when you saw Corporal Little shot dead?’ I would have liked to hear the reply.”

And he is just as good at demolishing the presumption of the academics-with-condescending-tones who are wont to explain, to the delight of the historyless youths in their charge, how the primitives of England in the 1940’s were fed a steady diet of propaganda that “inflicted” lasting damage on “intelligence, honesty, complexity, ambiguity, and irony.” “The British people,” Fraser reminds us, “were not stupid; they had been to war before, and knew all about its realities at first hand. . . . [H]ow you can inflict damage on complexity, ambiguity, and irony, is not clear to me or, I suggest, to anyone who prefers plain English to jargon. Obviously the war influenced people’s thinking permanently, hut to call such shaping of the mind ‘lasting damage’ is fatuous. One might as well say that forty years of comparative peace have inflicted ‘lasting damage’ on modern intelligence, and adduce modern theories about the 1940’s as proof.”

The war has certainly not inflicted any lasting loss of irony on Fraser’s sharp mind. He muses on how he, though too young to vote himself, sympathized with his colleagues who were conspirators against the greatest statesman of our time—growling, jowly Winston. In his case, it was because the Labour candidate for his home constituency was a patient of his father, a Scots physician; he also genuinely sympathized with his fellow soldiers who wanted a Great Britain that guaranteed them freedom from the terrible insecurity of the Depression, They got that, but lost much more. The Britain, Fraser laments,

they see in their old age is hardly the “land fit for heroes” that they envisaged. . . . They did not fight for a Britain which would be dishonestly railroaded into Europe against the people’s will; they did not fight for a Britain where successive governments, by their weakness and folly, would encourage crime and violence on an unprecedented scale; they did not fight for a Britain where thugs and psychopaths could murder and maim and torture and never have a finger laid on them for it; they did not fight for a Britain whose leaders would be too cowardly to declare war on terrorism . . . they did not fight for a Britain where children could be snatched away from their homes and parents by night on nothing more than the good old Inquisition principle of secret information; they did not fight for a Britain whose churches and schools would be undermined by fashionable reformers; they did not fight for a Britain where choice could be anathematized as “discrimination”; they did not fight for a Britain where to hold by truths and values which have been thought good and worthy for a thousand years would be to run the risk of being called “fascist”—that, really, is the greatest and most pitiful irony of all.

No, it is not what they fought for—but being realists they accept what they cannot alter, and reserve their protests for the noise pollution of modern music in their pubs.

The truth today is, unfortunately, everywhere an object of reeducation. But if you get a chance to hop across the pond, do pick up a copy of George MacDonald Fraser’s book and restore your sense of belonging to a brotherhood of men who fight and endure for causes that, whether they end in victory or defeat, are, alas, always betrayed by powerful men who don’t keep the faith. Nil desperandum.

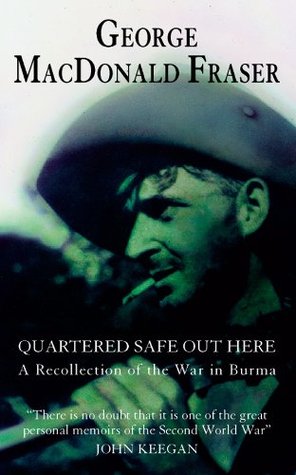

[Quartered Safe Out Here: A Recollection of the War in Burma, by George MacDonald Fraser (London: Harvill/HarperCollins) 225 pp., £16.00]

Leave a Reply