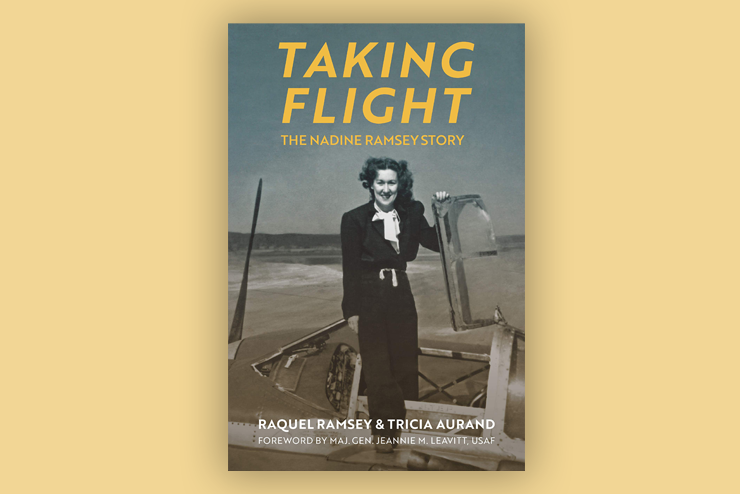

Taking Flight: The Nadine Ramsey Story; by Raquel Ramsey and Tricia Aurand; University Press of Kansas, 2020; 312 pp., $29.95

Taking Flight tells the remarkable tale of a courageous woman, Nadine Ramsey, who survived a difficult childhood to become Kansas’ first female commercial pilot, a World War II WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilot), an instructor of male fighter pilots, and a crusader for WASP veteran status. Her story should serve as an inspiration to all, especially to those who come from less-than-ideal circumstances and face seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Ramsey’s story demonstrates what pluck, perseverance, and an indomitable spirit can do.

Nadine was born to Claude and Nelle Ramsey in Illinois in 1911. A second daughter was born two years later, but as a toddler the younger girl pulled a pot of boiling water onto herself and died of the burns. The family was devastated. A boy, Ed, arrived in 1917, and Nadine immediately attached herself to her little brother. They would remain close for the rest of their lives.

Claude was from a farming family, but he left the farm to work in oil fields, first in Carlyle, Illinois, where the Ramsey children were born, and then in El Dorado, Kansas. When the oil boom began to decline in El Dorado, Claude was off to new strikes in Oklahoma and Texas, leaving the family behind in a wood and tar paper house. He returned home every few months, growing ever more convinced that Nelle was unfaithful to him, though he found nothing to justify his suspicions. Moody and angry, he drank heavily.

One night, with a verbal battle raging in their parents’ bedroom, Nadine and Ed heard the word “gun.” They raced into the bedroom in time to see their father pulling his shotgun from behind a headboard. Nadine, 16, and Ed, 10, threw themselves onto Claude and held on with all their might. Suddenly sober and ashamed, Claude dropped the shotgun and walked out of the house. Nadine called the police and described what happened. When officers arrived, they found Claude standing in front of the house. Later that night, alone in a jail cell, Claude hanged himself.

The family was now economically dependent on Nelle, who owned a cosmetology business, though Nadine and Ed also got part-time jobs. Nadine graduated from high school and spent a year at El Dorado Junior College before the crash in 1929 forced her to drop out and go to work full-time.

Nelle moved the family to Wichita, Kansas, in 1930, which was home to several aircraft manufacturers. The town had held its first air show in 1911. Living in Wichita were aviation pioneers Lloyd Stearman, Walter Beech, and Clyde Cessna. By the 1930s, Wichita, which had been one of the Kansas cattle towns at the end of the Long Drive from Texas, had become an aircraft town. Bold and adventurous, Nadine became obsessed with aviation.

Working hard as a secretary and saving her earnings, Nadine had enough money to begin flying in 1936. After fewer than seven hours of instruction, she soloed. A photographer from The Wichita Beacon snapped a shot of her standing next to the plane, and that photograph appeared in the newspaper. Women pilots were still a novelty. Some 40 hours of flight time later she had her private pilot’s license. A year later she became the first woman in Kansas to earn a commercial pilot’s license.

Working hard as a secretary and saving her earnings, Nadine had enough money to begin flying in 1936. After fewer than seven hours of instruction, she soloed. A photographer from The Wichita Beacon snapped a shot of her standing next to the plane, and that photograph appeared in the newspaper. Women pilots were still a novelty. Some 40 hours of flight time later she had her private pilot’s license. A year later she became the first woman in Kansas to earn a commercial pilot’s license.

In May 1938 during National Air Mail Week, J. B. Riddle, the postmaster of Wichita, swore in Nadine as an air mail pilot. The Wichita Eagle, the Beacon’s rival, headlined, “Wichita Aviatrix May Become First Woman to Fly U.S. Mail.” The newspaper had it wrong, but Nadine was among the first of several women pilots nationally to become mail pilots. When she flew the mail from Wichita to Wellington (another Kansas town), she was greeted by a large crowd of cheering citizens.

Nadine had higher aspirations than mail runs in Kansas. In 1939 she moved to Manhattan Beach in Southern California. Nearby were aircraft manufacturers Douglas, North American, Northrop, and Lockheed. She bought a plane, and the auburn-haired aviatrix became her own one-woman flight school, training young pilots and attracting the attention of Hollywood celebrities. This fame earned her a dealership from Taylorcraft, which produced a two-seat, high-wing, single-engine airplane that was relatively inexpensive and highly popular.

Nadine was now living the life of her dreams. But that life came to an abrupt halt when a powerful downdraft caused her to clip the top of a tree and crash to the ground while flying in the mountains of San Diego’s backcountry. She survived but suffered severe injuries, including a broken back and a leg damaged so badly that surgeons considered amputation. It was thought she might not walk again, let alone fly.

Her brother, Ed, dropped out of law school and rushed out to care for her. Ed told her he’d get her back into a plane even if he had to drag her by the hair. Both were high spirited, stubborn, and independent, and day by day Nadine improved. By Christmas 1940 Nadine was taking her first steps. In February 1941 she was back in the cockpit.

Within weeks she was as sharp as ever, and her rapid return to proficiency would soon come in handy, because the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor came in December. Nadine desperately wanted to contribute to the war effort, not only because she felt it was her patriotic duty, but also because her brother Ed was now Lieutenant Ramsey and fighting in the Philippines. When Bataan fell, he refused to surrender, instead fleeing into the bush to conduct a death-defying three-year guerrilla campaign against the Japanese.

In 1942 Nadine became an instructor for the Civil Air Patrol and in 1943 was accepted into the training program that would soon be known as WASP. The training was rigorous and differed little from that of Army Air Forces pilots. Nadine graduated in September—though two of her closest friends died in crashes before graduation—and soon began ferrying a variety of planes, including all of the single-engine fighters and, eventually, the twin-engine, twin-fuselage P-38 Lightning that leading aces Dick Bong and Tommy McGuire made famous. The Kelly Johnson-designed fighter required a highly skilled pilot to fly it, especially when an engine failed. Nadine became one of only 26 WASPs to pilot the Lightning.

Just before Christmas 1944, WASP was disbanded. The women pilots had ferried thousands of planes and flown thousands of hours. Thirty-eight of them had died doing their duty. Despite the inherent dangers in flying, most of the WASPs were not ready to quit, but the military pipeline was now churning out more than enough pilots. After two years of adventure, many of the WASPs had trouble readjusting to a conventional life. Nadine was one of the lucky ones. She was hired as an instructor for military pilots transitioning from transport planes or bombers to fighters. This might not have been as exciting as ferrying a P-51 or P-38, but she was still in aviation.

The next year she bought her own Lightning at a military surplus sale for $1,250. Newspapers ran stories about it. The Los Angeles Times titled its story, “Woman goes shopping; flies home with P-38.” The rest of Nadine’s life would be full of adventure and take twists and turns that could be the stuff of a novel.

Taking Flight is not a novel, though, but an exceptionally well-written biography that is painstakingly researched and fully documented. Moreover, authors Raquel Ramsey and Tricia Aurand go well beyond Nadine’s personal story, putting everything she did in the larger context of aviation during the 1930s and ’40s and of the nation’s history in that same period. Taking Flight also provides a history of WASP and the long campaign to achieve military veteran status for those pioneering women.

Leave a Reply