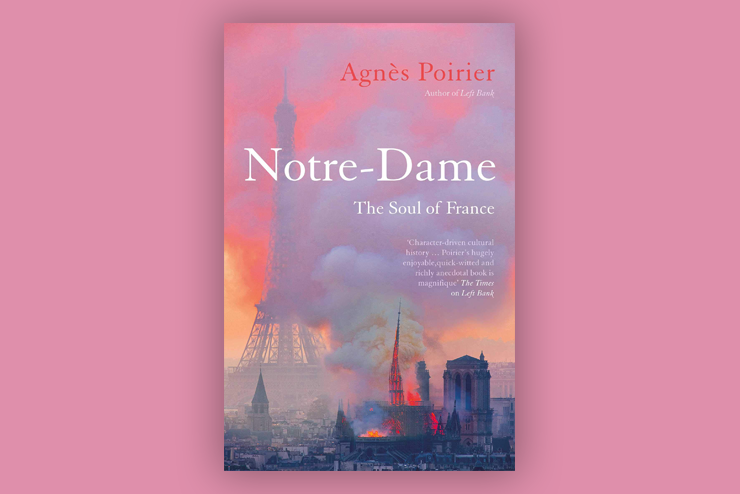

Notre-Dame: The Soul of France; by Agnès Poirier; One World Publications; 256 pp., $26.95

Kneeling in public remains rare in France. Even though Muslim crowds in the banlieues (suburbs) have recently taken to praying in the streets, religious display still shocks the country’s secular ethos, which prefers to severely confine religion to the private sphere.

So, when a motley lot of tourists and locals fell on their knees in witnessing Notre-Dame’s spire and 13th century wooden roof ablaze on a spring afternoon in 2019, foreign correspondents largely failed to grasp the moment’s deep religious significance. France’s wider reaction to the fire—and the ensuing uncertainty over the cathedral’s future—revealed a paradox: A nation notorious for its public laïcité (often translated as “secularism”) and declining faith suddenly embraced its deep Catholic roots.

Agnès Poirier’s book recounts in a dramatic fashion those grave and heady hours, as well as many other key moments in Notre-Dame’s esteemed history that have bound its fate to that of France. It is a timely reminder that under its thick layer of secularism, France remains staunchly Catholic at heart.

Paris was Christendom’s second capital and the seat of a powerful diocese when Bishop Maurice de Sully ordered Notre-Dame built in 1160. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, tasked with restoring it in the 1830s after the desecration wrought by the French Revolution, famously described its first three centuries of life as its “splendor” and the following three as having “obscured” that splendor. He was referring to Notre-Dame’s marked decline from the 15th century onwards, aggravated by the self-absorbed megalomania of an absolute monarchy, which began centralizing the power it had previously shared with the Church while removing itself from public accountability.

When Louis XIV moved the royal court to Versailles in 1682, Notre-Dame became one of the last vestiges of aristocratic Paris. A new spirit would enliven the city in 1789—to Our Lady’s detriment. Although the revolution displayed a faux Catholic piety at its onset—the crowd of sans-culottes who stormed the Bastille on July 14 capped their feat with a Te Deum prayer for freer and fairer futures—a creeping atheist fervor soon replaced it. The established clergy’s long-standing privileges were abolished and a new state-sponsored priesthood was formed, leading Pope Pius VI in 1791 to officially exclude France from Christendom, thereby establishing the so-called French Schism.

The revolutionaries even melted down Notre-Dame’s bells into cannonballs and decapitated the heads of the 28 Kings of Judah lined up on its west façade, mistaking them for French kings. Notre-Dame was turned into Le Temple de la Raison, with busts of Enlightenment philosophers lining both ends of the nave. Rationalism was France’s new religion d’état.

Napoléon, who emerged to channel revolutionary fervor into pragmatist statecraft, knew Catholicism couldn’t be uprooted from a nation that had been so defined by it, and that for the ideals of 1789 to triumph in Catholic Europe, they had to be reconciled with the Church. On July 15, 1801, he hosted Pope Pius VII to make amends, and signed a concordat with him that restored the Church’s status. The pope was present again at Napoléon’s coronation three years later at Notre-Dame, although he likely wasn’t delighted to kneel for 90 minutes waiting for Bonaparte to crown himself after skipping communion.

For all his smug disdain of churchly ritual, the self-proclaimed emperor had pulled off an elusive synthesis of religious and civilian power. When the Napoleonic experiment ended in 1814, Louis XVIII still felt the need to mark the restoration with a penitential Te Deum at Notre-Dame for all the revolution’s anti-religious sins.

The cathedral’s by then decrepit state didn’t raise alarm until the 1830s, when a distinguished cadre of historians and archeologists began calling attention to the country’s severance from its medieval past. Chief among them was novelist-historian Victor Hugo, whose “Note sur la destruction des monuments en France” in 1825 set the stage for a deeper treatise in 1832, “Guerre aux démolisseurs,” (“War on the Demolishers”) which called for a halt on all demolitions of medieval landmarks and for the state to instead repair “the countless degradations and mutilations which time and men had simultaneously inflicted.” Later, Hugo published three massive, richly illustrated volumes weaving a fictional tale with the cathedral as its chief setting. We know it in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

The novel’s minute descriptions of the cathedral’s stonework border on the tedious, but Hugo’s aim was justified. He sought to revive interest in Notre-Dame’s architectural splendor while implicitly denouncing the era’s “chintzy medieval fad,” an expression Poirier uses to define the superficial refashioning of all things medieval that had taken hold of Hugo’s romantic peers.

The novel’s minute descriptions of the cathedral’s stonework border on the tedious, but Hugo’s aim was justified. He sought to revive interest in Notre-Dame’s architectural splendor while implicitly denouncing the era’s “chintzy medieval fad,” an expression Poirier uses to define the superficial refashioning of all things medieval that had taken hold of Hugo’s romantic peers.

Ironically, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame chalks up the decline of great architecture at the time to the invention of the printing press. The novel’s antagonist, Claude Frollo, points from a book on his desk to the silhouette of the cathedral through a stained-glass window, uttering an ominous line: “This will kill that.” The narrator reiterates this conceit in a subsequent chapter: “The book will kill the edifice.” Hugo sought to communicate mankind’s achievements through “books of stone,” yet believed that writing was turning European man away from the palaces and cathedrals of his patrimony.

Hugo’s medievalism, however, was at odds with his progressive politics. In the so-called July Revolution of 1830, he supported the overthrow of the illiberal King Charles X and his replacement by his more progressive cousin Louis Philippe, who enlisted a taskforce of intellectuals to advise on restoration of the nation’s architectural glories. Prosper Mérimée, himself a literary man, was named inspector of historic monuments. Restoring medieval hallmarks to their erstwhile luster didn’t entail, in Hugo’s view, turning back the clock on the political advances made since 1789. “A universal cry must now call for the new France to come and save the old one,” he wrote in Guerre aux Démolisseurs.

Viollet-le-Duc, whom Mérimée in turn hired as Notre-Dame’s chief restorationist in 1838, is often associated with the so-called Henri II style—a baser, more superficial version of Hugo’s neo-medieval vision that Poirier labels “medieval bizarrerie”—but the imprint he left on the cathedral transformed it. He restored its gargoyles, façade, statuary, Kings of Judah statues and added the flèche (spire) that would so tragically burn down in 2019. Viollet-le-Duc’s work was so thorough that many architects and scholars to this day consider Notre-Dame more a work of 19th century restoration than of 12th century architecture.

Charles-Louis Napoléon, who revived his uncle’s imperial dreams by turning the Second Republic into the Second Empire through a coup d’état in 1852, had been so pleased with Viollet-le-Duc’s zeal that he chose Notre-Dame as the site of his marriage to Eugénie de Montijo in 1853. Shortly after, however, he entrusted Baron Georges-Eugène Haussman with a vast agenda of urban renewal that, along with redesigning Paris’ major roads and boulevards, would free the cathedral from the clutter surrounding it, which meant de-anchoring it from its historical context. Houses, narrow alleys, and guest houses that had forever lived in its shadow were torn down or remade.

The 20th century was also momentous for Notre-Dame, although the story of her preservation from Nazi bombs would not be known until long after World War II. In 1940, United States Ambassador William C. Bullitt, Jr., having heard of the Luftwaffe’s plans to make rubble of the city, rushed to beg Field Marshal Georg Von Küchler for mercy. He succeeded in sparing Paris and Notre-Dame the fate of Dresden. This was one among many episodes in France’s storied friendship with the American people, which Poirier narrates. Another one of these was the three-day national mourning the revolutionaries declared in June 1790 upon the passing of Benjamin Franklin—an ambassadorial predecessor of Bullitt, Jr. The rousing eulogy for the occasion was given by the Marquis de Mirabeau at the National Assembly.

Paris was liberated from the Nazis on Aug. 25, 1944 by General Philippe Leclerc’s Second Armored Division. His superior, Charles De Gaulle, was too conscientious of France’s deep Catholic roots to leave Notre-Dame on the sidelines of that joyful day. He was lucky to survive the Te Deum convened for the occasion, as Nazi holdouts rained down gunfire upon him from the upper gallery of the cathedral’s north tower.

Poirier’s book is a pioneering appraisal of Notre-Dame’s towering presence throughout France’s troubled experiments with the state-sponsored religion of the absolutist monarchs, as well as the absolutist secularism of the republicans. But her work isn’t backward-looking—instead, it underscores the vertiginous soul-searching prompted by the task of reconstructing the cathedral from the debris the fire left in its wake. Whether the French like it or not, “the tragedy revealed that their staunchly secular country has its roots deeply planted in a history that was Christian,” she writes in a moving afterword.

The dilemma of whether to reaffirm or shun the country’s Christian roots is so fraught with national significance that many have called for a plebiscite on reconstruction that would override President Emmanuel Macron’s unilateral handling of the controversy. The dilemma is highly contentious, too. France’s chief architect for historical monuments, Philippe Villeneuve, was unceremoniously shushed by Jean-Louis Georgelin, former Army Chief of Staff, as the latter briefed the National Assembly’s Cultural Affairs Committee on the cathedral reconstruction efforts. Villeneuve’s offense? To have channeled the views of 54 percent of the French in calling for the spire to be restored to its original condition before the fire, rather than remade in a more modern design.

The dilemma of whether to reaffirm or shun the country’s Christian roots is so fraught with national significance that many have called for a plebiscite on reconstruction that would override President Emmanuel Macron’s unilateral handling of the controversy. The dilemma is highly contentious, too. France’s chief architect for historical monuments, Philippe Villeneuve, was unceremoniously shushed by Jean-Louis Georgelin, former Army Chief of Staff, as the latter briefed the National Assembly’s Cultural Affairs Committee on the cathedral reconstruction efforts. Villeneuve’s offense? To have channeled the views of 54 percent of the French in calling for the spire to be restored to its original condition before the fire, rather than remade in a more modern design.

The spat was a mere clash of egos, but some of the restoration ideas proposed by French politicians were stupidly barbaric, plainly in keeping with the debased secularism of large sectors of European society. An accident that threatened a sacred monument of Western civilization was seen by some as an opportunity to promote such “woke” shibboleths as urban biodiversity, an example of which was the Swedish proposal to replace Notre-Dame’s flèche with a rooftop animal zoo and swimming pool. Macron, thankfully, has recently sided with Villeneuve and the French people in calling for the spire to be restored to its original design.

Poirier’s chronicle of the heady hours following the first reports of the fire largely papers over just what exactly caused it. Islamophobic conspiracy theories were quickly dismissed, but the hypothesis of a faulty light bulb in the scaffolding embraced in their stead has strangely failed to trigger outrage, even though bringing electricity anywhere close to the vaulted wooden roof of an 850-year-old cathedral would surely seem reckless. This is not to mention the long record of prior neglect that Poirier denounces in her book.

In the fire’s wake, the outpouring of donations from France’s wealthiest families is a measure of the country’s adoration of Notre-Dame or at least of widespread pride in France’s cultural heritage. Less heartening by contrast is the French state’s chronic underfunding of reconstruction efforts, which played a part in triggering the fire in the first place. The mismatch between the two, as Poirier’s telling makes clear, is a byproduct of misaligned incentives.

Both the state and the Church have a stake in the building’s preservation. On the one hand, the state, which has owned the building since 1905, is torn between countless spending priorities, many of them urgent; on the other, the Archdiocese of Paris, which oversees masses and manages tourist inflow, has been dissuaded by its position as a mere rent-free occupant from raising the restoration money that the state has fallen short of providing. An entrance fee of a few euros could have prevented the underfunding, but the moral hazard stealthily introduced in 1905, when the state assumed nominal ownership of all the nation’s cathedrals, meant that neither the archdiocese nor the Ministry of Culture felt enough primary responsibility for investing in Notre Dame’s future to charge such a fee.

The COVID-19 crisis has brought Notre-Dame’s reconstruction to a sudden halt, and uncertainty looms over Macron’s plans to restore Our Lady to her eternal glory within five years. When the dust settles and builders pick up the torch carried by her anonymous 12th century architects and by the earlier restorationists such as Viollet-le-Duc, France should be reminded that reconstruction of Notre-Dame is a chance to reaffirm its Christian roots—and to say plus jamais ça! (Never again!) to accidental fires.

Leave a Reply