Philip Larkin, the poet-librarian of Hull University, died December 2, 1985, over 29 years ago. In the years since Andrew Motion published the first biography (1993), and Anthony Thwaite published both the first complete edition of the poems (1989) and the first collection of letters (1992), a small industry has grown up devoted to the poet. There are archived collections at Hull, in the British Library, the Bodleian Library, and the Huntington Library. There is a Philip Larkin society with a journal. And if James Booth is right, insofar as a poet’s work can be popular these days, Larkin’s poems are very popular. People are still quoting him, and in a poll of several thousand readers in 2003, “The Whitsun Weddings” was voted the most popular poem of the last 50 years.

This is not an outcome one would have expected 20 years ago. It represents a small triumph of art over life—in this case, the poet’s own life. When Motion’s Life and Thwaite’s selection of the letters revealed Larkin’s private life and opinions to the general public for the first time, the result was a howl of condemnation from the keepers of correct opinion. Here was a man who, in his own words, adored Mrs. Thatcher, objected to the invasion of England by immigrants from the former colonies, and, in a letter to Robert Conquest, expressed his disgust with “the striking classes” in a savage quatrain:

I want to see them starving,

The so-called working class,

Their wages weekly halving,

Their women stewing grass.

In the later 60’s, he despised protesting students and the faculty members who supported them: “The universities must now be changed to fit the kind of people we took in: exams made easier, place made like a factory, with plenty of shop-floor agitation.” Nor did he care for the way the teaching staff joined the protesters, “calling meetings & issuing press statements & wearing the ‘campaign badge’ . . . one hag said she hadn’t been so excited since Spain!” He made those comments to the novelist Barbara Pym. To his friend Kingsley Amis he simply described the universities as “superfluous nests of treason-soaked layabouts.” These remarks did not go down well in academic circles.

Yet none of them could deny the power or the popularity of his poetry. Like his friend and compeer Sir John Betjeman, he had become a national treasure, so what was to be done about him? Larkin had answered that question himself in his own downright way years earlier, in the opening sentences of a review of a book on Wilfred Owen, the war poet: “A writer’s reputation is twofold: what we think of his work, and what we think of him. What’s more, we expect the two halves to relate: if they don’t, then one or other of our opinions alters until they do.”

James Booth was appointed to the English department at Hull in 1968, but although his time there overlapped with the later years of Larkin’s librarianship, he seems not to have known him well, if at all. What he does know is Larkin’s poetry, upon which he has published a good deal. Now retired, he is literary advisor and coeditor of the Larkin Society, and this is his third book on the poet. As one would expect from an English professor, Booth devotes much of his space to interpreting the poetry, in the process revealing occasional ignorances. For instance, he seems not to know that Larkin’s poem “Fiction and the Reading Public” takes its title from a snooty book by Queenie Leavis, famous in its time, about the decline of the public’s taste in fiction. Nor does he know that the reason Philip wanted to photograph Tranby Croft for Monica was that the house had been the scene of a famous case of cheating at cards involving Edward VII. As for his approach to Larkin’s life, since he admires the poetry but does not care at all for either Larkin’s politics or his social habits, he tries hard to make just the kind of alteration that Larkin’s sentence about Wilfred Owen describes.

His way of doing this is to point out that the people who knew Larkin well and worked with him, including his female staff, liked him very much, and that to understand his letters properly one needs to know two things about him: that he was a great player of roles, and that he adjusted his persona to his correspondents. His racier comments to Robert Conquest and Kingsley Amis about politics and sex, therefore, tell us more about them than about Larkin.

Booth even applies this rhetorical solvent to Larkin’s exchanges with his partner, Monica Jones. On one hand, he tells us that Monica—a lecturer in English and, like Larkin, an Oxford first—was the right woman for him because she was smart and understood him; but on the other hand she was also the wrong woman because she was a conservative who demanded that Larkin accept her “right-wing prejudices,” “rigid right-wing opinions,” and “unreflecting conservatism.”

As a revisionist argument in defense of Larkin, this one only goes so far, and brought up against Larkin’s own strongly felt opinions, Booth’s ultimate defense of his subject is, to all intents and purposes, a plea of insanity: “Personal insecurity” underlay Larkin’s disapproval of student rebels and lefties, and the only rational explanation for a letter to Amis summing up Larkin’s loathing of Harold Wilson’s Labour government is that “Personal unhappiness increasingly displaced itself in shallow political rant.” James Booth, it seems, is one of those people for whom a phrase like “rigid left-wing opinions” or “unreflecting socialism” would be a contradiction in terms, and therefore unutterable. The thought that Larkin could have been right is unthinkable for him—although I suppose it is always just possible that the spectacle of “English” jihadis going about decapitating actual English people might open a mind otherwise shut tight.

Booth’s radical lack of sympathy with Larkin is bound to damage his book about him, however much he claims to enjoy the poetry. His inevitably condescending account of Larkin’s life, like its predecessor by Andrew Motion, leaves one wishing that, if there are to be lives of Larkin, someone would simply start all over again, and on altogether different premises. To begin with, Philip Larkin was a very intelligent man who could not help writing well whatever the occasion or the form, and on top of that he was the successful creator, administrator, and manager of a large university library. I once heard an elderly academic say that the essential qualification for anyone wanting to teach at his rather distinguished college was to grasp the fact that most of the students were brighter than all but a handful of the faculty. Admittedly, humility does not come easily to the academic mind, but could an academic biographer of Larkin not operate on a similar principle, and assume that his subject was probably brighter than himself?

Philip Larkin and his friend Kingsley Amis were the two most successful serious writers of their generation in England. They were both products—like their heroine Mrs. Thatcher—of the new middle class that appeared in England between the wars, and they made a new kind of English style out of its ways of speaking and thinking. In a letter to Robert Conquest, Larkin summed up their approach as “plain language, absence of posturing, sense of proportion, humour.” Larkin and Amis were very funny men, and both were conservatives, although like so many others in those days, Amis had started out on the extreme left as an undergraduate. Even Larkin—as he told Monica Jones—had had “a prejudice for the left” because the writers he’d liked had all been nonpolitical or left-wing, and at that age he’d not been able to find “any right-wing writer worthy of respect.”

Both insisted, too, that they were atheists. Why wouldn’t they be? Neither received any religious formation at home, and the religious teaching provided in English schools in those days, though full of Bible reading, was quite empty of theological content. Amis, who described himself as an unwilling unbeliever, and who knew that faith was a gift, came from a nonconformist background, and, as he said in an interview, something of its virtues remained in his father’s approach to life—thrift, hard work, patience, sticking to things. He was grateful for that. As for the Church of England, her shenanigans distressed him because he wanted the church preserved for his grandchildren.

Larkin, of course, is famous for “Church Going,” a poem about his habit of visiting churches. He also liked to go to choral evensong, and, atheist or not, he told Barbara Pym that a sight of Archbishop Ramsey (for many people the last real Anglican archbishop of Canterbury) had cheered him up. In a poem called “Compline” —not mentioned by Booth—about listening to a broadcast service, the possibility that God might answer one prayer out of millions keeps him from “quenching” the prayer—i.e., turning the broadcast off.

James Booth has no time for religion. He thinks T.S. Eliot’s religion was self-deception, and he describes Monica Jones’s funeral as “a very Anglican affair with much mumbling and a brightly encouraging organ.” Not surprisingly, just as his leftism prevents him from taking seriously Larkin’s rage at the socialists’ destruction of England, so his dislike of religion prevents him from grasping the subtleties of Larkin’s treatment of it. When the two subjects come together in a commissioned piece, “Going, Going,” Booth brushes the poem off as “tragic portentousness” assumed for the occasion. That is not the way it strikes a sympathetic reader:

For the first time I feel somehow

That it isn’t going to last,

That before I snuff it, the whole

Boiling will be bricked in

Except for the tourist parts—

First slum of Europe: a role

It won’t be so hard to win,

With a cast of crooks and tarts.

And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the

lanes,The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There will be books; it will lin-

ger onIn galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres.

“Going, going,” says Booth, “contains the only unambiguously positive use of the word ‘England’ in his poetry; and it strikes a false note.” Oh, no: Larkin meant the word and the poem, and although poor Larkin snuffed it sooner than anyone expected, quite a lot of people contemplating the present state of England would say that he was not altogether wrong.

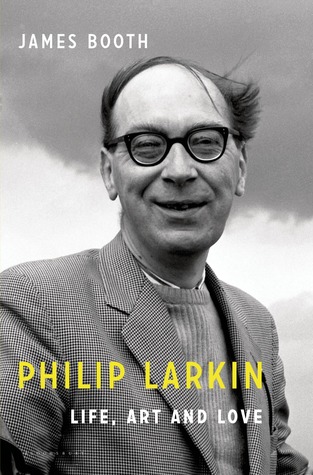

[Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love, by James Booth (New York: Bloomsbury Press) 518 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply