The Burma campaign included some of the most charismatic and colorful soldiers of World War II: Vinegar Joe Stilwell and his X-Force, Claire Chennault and his Flying Tigers, Frank Merrill and his Marauders; the British commanders Harold Alexander, William Slim, Archibald Wavell, Claude Auchinleck, Orde Wingate and his Chindits, and Lord Louis Mountbatten, luxuriously ensconced in his headquarters in distant Ceylon; Chiang Kai-shek, Stilwell’s commander and enemy; the Burmese nationalist Aung San (father of the current Burmese leader), who first supported the Japanese, belatedly joined the British in March 1945, and was assassinated by a rival political faction in 1947; the wild Naga tribesmen who served as guides, the ear-slashing Kachin Rangers, and the 60,000 slave laborers who built the Kwai railway.

The Burma campaign began in January 1942 with the Japanese invasion from Thailand in the south. Chinese troops, with Stilwell as Chiang’s chief of staff, invaded from the east, along the 715-mile Burma Road from Kunming to Lashio. After their initial defeat, the Chinese retreated to China; the British, to India. Stilwell led 100 Americans, including the Burma missionary-surgeon Gordon Seagrave, on foot and without losing one man, across the Indian frontier. The Japanese controlled Burma; the Allies reorganized for an offensive.

The Flying Tigers, operating from Kunming, supported the remaining Allied troops in Burma. Stilwell supplied the Chinese and kept them in the war by flying from Assam, over the Himalayas, to Kunming. Wingate’s Chindits conducted guerrilla warfare against the railroads but were also forced back to India. During the British-Chinese invasion, the Chindits landed in gliders. Wingate was later killed in an air crash. After fierce jungle fighting, the Allies captured the crucial railhead at Myitkyina and continued southward despite the monsoons. The Chinese were forced to withdraw because of Japanese advances in southern China.

In a new offensive, the Japanese advanced upon British headquarters at Imphal, near the Indian border. The Burma Road was reopened, and the first convoy reached China. Allied troops—converging from India, northern Burma, and China—had overwhelming air support. In May 1945, the Japanese, cut off from supplies and weakened by battle, malaria, and starvation, were driven back into Thailand. It is cruelly ironic that, after the Allies changed strategy and decided to attack Japan through the Pacific islands, the overland approach to Tokyo became unnecessary. The fiercely contested “Burma Road had become obsolete even as it was being opened.”

A few interesting details added by Webster include the fact that some Japanese soldiers were found chained to stone buildings, left with a scanty rice ration and a bit of ammunition to face the overwhelming enemy. Japanese prisoners choked themselves to death by eating their blankets. Chinese soldiers marched with the curious bitterness of men “who expected nothing but disaster.” When a badly wounded American airman parachuted into a very tall tree and could not be rescued, his crewmen drew lots to decide who would have to shoot him. Suddenly, Kachins appeared from the jungle, “felled a smaller tree against the larger one, and climbed one hundred feet up the ‘ladder tree’ to rescue the injured sergeant.”

There are, nevertheless, some errors and serious misinterpretations in this book. The Irrawaddy (I have sailed on it) does not become “bone dry” in February; Gandhi rose to prominence in 1915—not 1942. And Webster, who tends to ignore the British commanders except when they oppose Stilwell, underestimates Lt. Gen. Alexander, who (after Burma) successfully led the North African campaign and the landings in Sicily and Anzio, captured Rome, conquered Italy, and became a field marshal in 1944.

Stilwell clashed with Chiang—whom he called “a stubborn, ignorant, prejudiced, conceited despot”—over the generalissimo’s refusal to arm his own unreliable soldiers, who might revolt, and to concentrate his forces in large groups, which he feared might be destroyed by a single Japanese attack. Webster is dead wrong in concluding that,

For Stilwell, after nearly three years of “bickering” and “dickering,” his victory over Chiang was complete. At long last, he had humiliated the generalissimo, making Chiang lose face in front of his own subordinates.

Insulting an Asian despot is not the way to victory. Chiang swallowed the toad but made certain that Stilwell—despite his intelligence, courage, and victory in battle—was relieved of his command and became a “fugitive from the Chiang gang.”

By emphasizing Stilwell, Webster distorts the realities of the overwhelmingly British campaign. When Errol Flynn’s film Objective, Burma! (1945) opened in Britain, critics attacked it for claiming that Americans in general, and Flynn in particular, were winning World War II single-handedly. At a command performance, King George VI sharply questioned Flynn about his role; and the movie, booked into 500 cinemas, had to be withdrawn from view. The best works on the war in Burma remain William Slim’s Victory in Defeat (1956), Barbara Tuchman’s Stilwell and the American Experience in China (1971), Bierman and Smith’s life of Wingate (1999), and Ian Watt’s brilliant essays about his prisoner-of-war experience on the Kwai railway, one of which was reprinted in The Literal Imagination (2002).

Webster includes almost no description of the Burmese landscape, towns, and people, or of the inhuman Japanese treatment of the civilian population. The fast-flowing rivers, the houses built on stilts to protect against flooding, the herds of spindly goats wandering along the road, the water buffalo immersed in mud, and the lush green mountains in the distance recall the atmosphere of Joseph Conrad’s Malayan novels. Mandalay, a sprawling city in central Burma, is flat, hot, and dry. A British memorial tablet on Mandalay Hill, which has many pagodas and spectacular views, marks the bitter, costly Gurkha assault on that Japanese stronghold in March 1945. Two months later, the Burmese royal palace and the English police barracks inside the fort, surrounded by high crenellated walls and a wide moat, were destroyed by British bombers.

At Thanbyuzayat, in southeast Burma, a tidy park maintained by the British War Graves Commission emerges from a jungle setting. Here lie hundreds of English, Australian, Dutch, Indian, and Gurkha prisoners of war who died while building the Siam railway for the Japanese. Some of them were unknown soldiers, and one was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Since officers had a much better chance of survival, most of the dead were young enlisted men. This military cemetery recalls Kipling’s story “The Gardener,” in which a grieving woman visits her lover’s war grave amidst a “merciless sea of black crosses.”

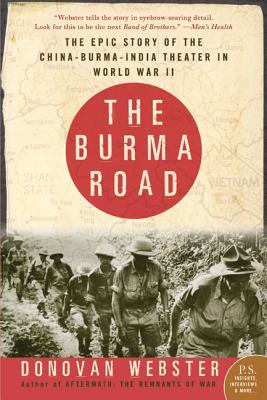

[The Burma Road, by Donovan Webster (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux) 370 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply