The History Book Club has done us a good service by reprinting Leon Wolff’s Little Brown Brother, published originally in 1960, before we had learned to be politically correct or had figured out that we were building an empire. In fact, in 1960, most of us had not realized that our foreign policy had been taken over by the ideology of liberal internationalism, or what Max Boot now wants to call “Conservative Internationalism.”

How long ago was 1960? John F. Kennedy was accusing Richard Nixon and Dwight Eisenhower of being so soft on commies that they had allowed a “missile gap” to develop. Some voters actually believed him. One wishes that Kennedy had read Mr. Wolff’s little classic instead of Michael Harrington’s The Other America or the manual of empire produced by the Rockefeller brothers, Prospect for America.

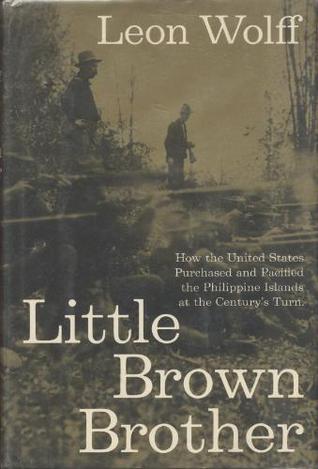

Little Brown Brother is remarkable for winning the Parkman Prize of the Society of American Historians—while failing to contain a single footnote! The Introduction to the new edition, written by Paul A. Kramer of Johns Hopkins University, does have footnotes and criticizes Mr. Wolff for their absence. One might suspect that both Mr. Kramer and the History Book Club have other than good intentions in resurrecting this fine old volume. In fact, Mr. Kramer calls it a “crude” book. (It came out before the emergence of language police.) Leon Wolff was an old Progressive, given over to empathy with “little guys.” He wrote this book to bring to light a story that had been buried for decades, as indicated by the subtitle, “How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn.” He tells it evenhandedly. Despite the invincible ignorance of President McKinley, the remarkable arrogance of Theodore Roosevelt, and the utter viciousness of the American military, Mr. Wolff does not make this historical episode into a morality play. It is not a tale of “little brown guys, good, and big white guys, bad.”

The final demise of the Spanish Empire caught a lot of people by surprise. Germany, England, Russia, Japan, China, and the United States all had hard decisions to make and not much real knowledge to go on. A friend of mine, a good historian and observer of the Middle East, told me in 1991 that the United States had maybe 50 people who knew Arabic well enough to give good advice to the George H.W. Bush administration. I doubt that, in 1898, the United States had 50 people who could tell you anything specific about the Philippines.

And yet we “purchased and pacified” them after the fiasco of the Spanish-American War. Fewer than 400 Americans died “liberating” Cuba; over 4,000 died pacifying the Philippines. And we killed over 200,000 Filipinos. The total population of the islands was less than eight million. Henry Adams, still a good friend of Teddy Roosevelt, wrote, just as the slaughter was getting under way,

I fully share with [Senator] Hoar the alarm and horror of seeing poor weak McKinley . . . plunge into an inevitable war to conquer the Philippines contrary to every profession or so-called principle of our lives and history. I turn green in bed at midnight if I think of the horror of a year’s warfare in the Philippines . . . where we must slaughter a million or two foolish Malays in order to give them the comforts of flannel petticoats and electric railways.

Mr. Wolff says that we came to the Philippines with the law in our hands, “and the law was progressive.” Of course it was. To bring the blessings of “liberty” (we weren’t yet calling ourselves a “democracy” very often) we had to deal with “insurgents.” It did not seem to matter that

The Filipinos also suggested that the terms “insurgent” and insurrecto be abandoned by the Americans. They had been insurgents against Spain, but they were now independent and the Americans did not own them. The Americans continued to call them insurgents.

The rhetoric is creepy in its similarity to what took hold in the 1960’s among Democrats, and to what comes out of Republican Washington today. The only difference is that President McKinley could call the beneficiaries of our liberty, with a straight face, “our little brown brothers.”

Mr. Wolff says that the American people, even by 1960, “had not yet fully grasped the magnitude of the Philippine war effort or the ruthlessness with which it was being waged.” Ruthless is the name of the game. James Kurth of Swarthmore and the Foreign Policy Research Institute recently said (I’m citing him from memory and not from a written text) that such successes as we have had in bringing the benefits of our liberty and prosperity to others have required the most destructive war in human history and the occupation of the losers’ countries for over 50 years. Are we willing to take that on again? Should we have learned something from “our little brown brothers”?

[Little Brown Brother, by Leon Wolff (Mechanicsburg, PA: History Book Club) 432 pp., $21.99]

Leave a Reply