In an established literary conceit, houses become people, and people become houses: Roderick Usher and the House of Usher, Quasimodo and Notre Dame. Similarly, people become their cities, and cities their people. Parisians is not an “important” book like Graham Robb’s magisterial work of the historians’ art, The Discovery of France. But it is indisputably a work of art by a master observer, historical researcher, and poet, and that work’s beauty is matched by its qualities as an entertainment at a high level. If Robb, an Englishman resident in Oxford, did not exist, it would have been necessary to invent him as evidence that the stereotype of the English traveler as the awkward, ignorant, philistine enemy of France and all things French is not be taken at face value. Graham Robb has been in love with France and the French since his student days. If one were willing to risk offending the equally stereotypical xenophobic Frenchman by suggesting that Robb understands France better than do many of the French themselves, then one would go ahead and say it. And I do say it.

Some of Parisians’ chapters are sketches; others are stories selected from the history of Paris. One is a mystery tale whose themes are Notre Dame, alchemy, and the making of the atom bomb; another is a screenplay; yet another (about the student revolt in 1968) is presented in the form of an academic exam, essay answers provided. On occasion, Mr. Robb does get carried off a bit by his own considerable poetic talent (a minor fault that is observable in Discovery as well). And he writes a sentence here and there that I read through several times before leaving it to what impressed me as its own inscrutable vagueness. (Again, I had the same experience in places while reading thorough the earlier book several years ago.) In any event, is it far better to strive for a particular effect and fall just short than not to try at all. Graham Robb tries with every sentence, and 99.9 percent of the time triumphs, or at least gets away with it.

There is not a flat or failed chapter among the book’s 20, whose settings run from the middle of the 18th century to the immediate present. The opening scene of “The Man Who Saved Paris” is the customs barrier on the Left Bank at the southern edge of Paris on the afternoon of December 17, 1774. With terrible suddenness the rooflines of the city adjust their position against the sky and vanish with a rush and a gigantic sigh in an immense dust cloud into the earth. Paris had built itself up out of its own bowels, excavating the ground beneath much of the city and leaving cavernous quarries of immense extent and at several subterranean levels. Two years later, the architect Charles-Axel Guillaumot is commissioned to save the remainder of the city from destruction. He accomplishes this task by constructing an elaborate mine support system to hold up the quarry ceilings. Later, when flooding washes the bones of the centuries-old dead from the city’s overcrowded cemeteries, Guillaumot adopts the obvious solution by filling up the quarries with medieval human remains, where they to this day remain (Guillaumot among them). The story is notable in combining historical charm with a sense of the macabre worthy of France’s favorite American writer, Edgar Allan Poe.

“Madame Zola” is a touching account of the loyal wife wronged by her famous but hypocritical husband, the socialist novelist Émile. And “The Day of the Fox” is a thriller about an assassination “plot” concocted by François Mitterand to enhance his stature and advance his career. But the most unforgettable chapter may be “A Little Tour of Paris,” about Hitler’s exploration of the city by car after the fall of France. Hitler is familiar with all the monuments, he knows the Opéra better than the janitor who gives him a tour of the house, and he instructs the German architect he has brought along to take notes so that he can reproduce the French capital in Berlin. Only, there are no people in the streets! Hitler is thrilled by the human absence: The perfection of Paris is the city’s architectural mass, unencumbered by the Parisians themselves. I don’t believe I have ever read anything that so perfectly captured Adolf Hitler’s utter, completely rational, insanity.

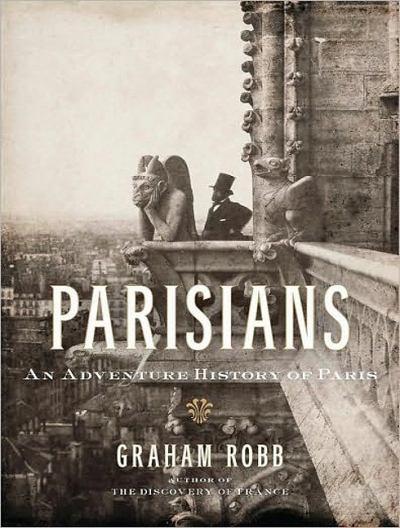

[Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris, by Graham Robb (New York: Norton) 476 pp., $28.95]

Leave a Reply