The publication of the last volume of William Marvel’s four-volume history of “Mr. Lincoln’s War” completes one of the more remarkable historical works of our time. Marvel is an “amateur,” nonacademic, historian. That is not a remarkable, but rather an old and honorable, thing. This is what is remarkable: I can think of no active “professional” historian of the Great Unpleasantness who exhibits anything like Marvel’s combination of broad scope, prodigious research, and integrity in the use of evidence.

The author reminds me of some of the old salts of the newsroom I knew during the years of my misspent youth as a reporter. These fellows had not been to college. But they could tell the difference between a fact and a conventional attitude, were skeptical of all authority, had no personal or ideological axes to grind, and were determined to dig out the real story and tell it, insofar as the publisher would permit them. Marvel recounts the Northern side of the great conflict as the evidence establishes it: a justifiable cause, perhaps, but not a righteous crusade without reproach. The author is by no means a Southern partisan (unlike the reviewer). He is a New Hampshireman. I am sure if he were to tell the Southern side of the war, he would display the less seemly bits as forthrightly as he has done in his history of Lincoln’s war. Nor is he, as far as I can tell, a muckraker anxious to cast dirt on every sacred cow. Like the old reporters, he tells it like it is, and he knows what he is talking about.

A “conservative” historian of some repute not too long ago praised the righteous rising of the American people after Fort Sumter, Pearl Harbor, and September 11. One has to be either a deep-dyed child of Massachusetts or an unabashed state worshiper more European than American to compare the reduction of Fort Sumter to the two massive sneak attacks by foreign enemies. The reduction of Fort Sumter was an attempt to resolve a legitimate constitutional dispute. It involved no secrecy and no surprise on the part of the attacker, no duplicity (except on the part of the Lincoln administration), and targeted no civilians. It was, in fact, a bloodless and gentlemanly exercise. And the other side, after all, were Americans, too—in fact a rather huge part of them—Americans acting honorably by the values of the time.

But that is not the primary problem with the reference to Fort Sumter. The primary problem is the assumption that the Northern people rose up as one in righteous anger to undertake the great mission of putting down the rebellion. There was a burst of recruiting after Sumter, but through the rest of the war Mr. Lincoln had great difficulties in raising the troops needed to destroy the independence of the fiercely resisting Americans of the South. It required bribery, coercion, the wholesale importation of foreign cannon fodder, the military suppression of dissenters without due process of law, and unprecedented war against civilians. And adding the emancipation of the slaves as a war aim probably cost Lincoln more Northern support than it gained. All in all, it is quite appropriate to call the war Mr. Lincoln’s war. Without him it might not have happened, or might have taken a very different course.

Mr. Lincoln’s war required a light touch on the respectable and dominant part of Northern society. Three hundred dollars bought immunity from conscription. Like Lincoln’s military-age son, no affluent Northerner ever served in the war unless he wanted to. And those who did, like Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Joshua Chamberlain, did so as much from a desire not to miss out on great events as from devotion to Lincoln and his cause. A great many Northerners regarded the war as a moneymaking arrangement or an ethnic cleansing to be carried out, like factory labor, by the working class. To call the Southern “rebellion” a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight is a glaring falsehood, as Northerners who actually had to face the Southern armies well knew and said. The same cannot be said of the Union effort.

For that matter, as Marvel suggested in his first volume (Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, 2006), the recruitment effort following Fort Sumter was enhanced by widespread unemployment in the Northeast. Mr. Lincoln Goes to War was followed by Lincoln’s Darkest Year: The War in 1862 (2008) and The Great Task Remaining: The Third Year of Lincoln’s War (2010). Another neglected aspect of the war that appears in these volumes as unvarnished fact is its massive corruption, which made many fortunes for well-placed Lincolnians but often left the poor soldier badly short-changed. To a significant extent, Lincoln had to buy support for his war, and was often doubtful even so of maintaining a majority in favor of it. Indeed, the Northern opposition to Lincoln, much larger and more respectable than has been allowed, is the great untold story of American history.

As seen in these volumes, Lincoln himself is no saint and no supreme genius. He makes mistakes, sometimes disastrous ones, is not above a bit of trickery against his own people, is devoted to deceptive rhetoric, and knows all the ins and outs of purchasing political support. Lincoln here is not an icon but a human being, flawed like the rest of us, and overwhelmed by the war he had begun in expectation of a quick victory. Lincoln’s divinity seems to be fixed in the American psyche beyond any facts or argument. But, alas, as M.E. Bradford warned long ago, he is a god we continue to worship at our peril.

The sins and shortcomings of the South, real and imaginary, have been explored and publicized superabundantly, and indeed “distinguished” scholarly careers are still being made by inventing new ones. It is much more pertinent that we know the sins and shortcomings of the Union side, because the phony sense of self-righteousness that arises from that crusade is still an active ingredient in the souls of American leaders, determining their often unwise exercise of power at home and abroad. To read through Marvel’s four-volume account of the Union’s war would be a healthy enterprise for every overproud American.

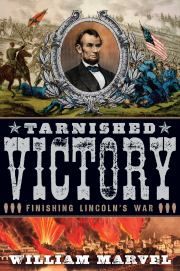

[Tarnished Victory: Finishing Lincoln’s War, by William Marvel (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) 478 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply