James Rosen’s biography shows Justice Scalia’s greatness in bucking the prevailing liberalism of the Supreme Court.

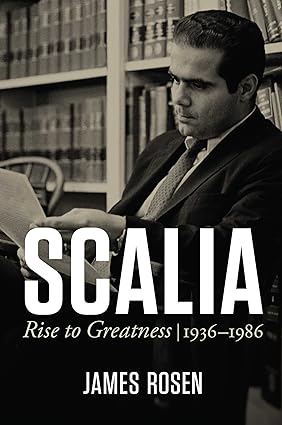

Scalia: Rise to Greatness, 1936-1986

by James Rosen

Regnery Publishing

500 pp., $39.99

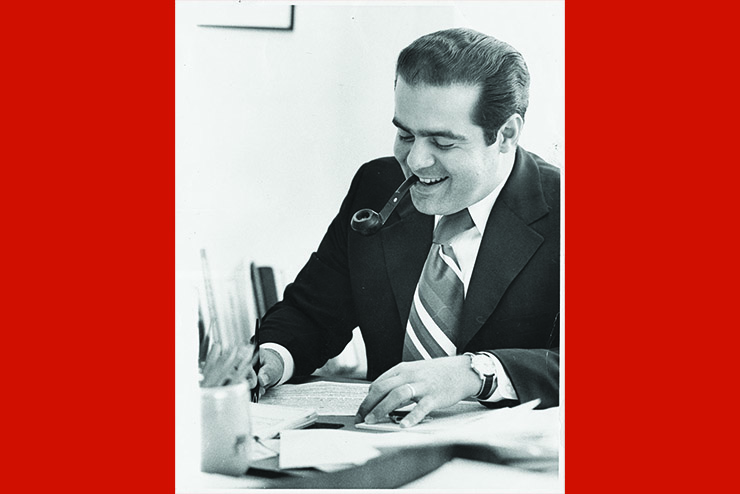

Antonin Scalia (1936-2016) was the first “celebrity” justice of the United States Supreme Court. The Winston Churchill of American judges, the “rock star” of One First Street, a man who virtually everyone who knew him seems to describe as “larger than life,” he was equally at home before the TV camera as he was in front of a podium, before a congressional committee, or on the bench eviscerating advocates.

Scalia was one of two justices (Clarence Thomas was the other) whom Republican presidential candidates repeatedly cited as their model jurists. But he was anathema in the law schools, since he was a leading exponent of originalism, the judicial philosophy that limited the meaning of the United States Constitution to the way it was understood at the time of its passage. Originalists like Scalia believe also that law-making should be limited to legislators and that the federal government should be of limited and enumerated powers.

By the second half of the 20th century, legal academia was dominated by so-called legal realists and by other theorists from purportedly scholarly fields such as feminism and gender studies, critical legal studies, and critical race theory. Unlike Scalia, these academics believed that it was the job of judges and justices to remake laws and the Constitution in a manner that better met the needs of Democrats by matching their progressive politics, which usually involved the expansion of the federal Leviathan.

Two previous books on Scalia—both critical of him—are the special target of this new biography by journalist James Rosen, the first volume of a projected two-part work. In those earlier tomes, CNN Legal analyst Joan Biskupic’s American Original: The Life and Constitution of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia (2009), and political scientist Bruce Alan Murphy’s, Scalia: A Court of One (2014), Scalia was limned as a failure, as the proponent of an archaic judicial hermeneutics and an acerbic personality too off-putting to be a coalition builder on the Supreme Court.

The story Rosen has to tell, however, is different. It is the account of a jurisprudential titan who climbed to the heights of the legal profession by dint of genius, and who laid the foundation for a recapturing of constitutional law. This first volume concludes with Scalia’s swearing in as associate justice on Sept. 26, 1986. In the next volume, Rosen presumably will seek to make the case for Scalia the justice. Nonetheless, there is enough in this work to build an argument that “Nino,” the “kid from Queens,” as Rosen calls him, was a great man.

Rosen is not a lawyer. As a recovering law professor, I began Rosen’s book skeptical of an outsider to the profession adequately evaluating Scalia. But my fears were groundless. This first volume is quite good on jurisprudential analysis, and Rosen has done a far better job than did Biskupic and Murphy in engaging in archival research. The author tells us no less than 28 times that he is presenting “previously unpublished” materials, and he has apparently interviewed virtually everyone alive who knew Scalia well. Scalia’s acquaintances and family paint him as a thoroughly affable human being and a hero to his clerks and other lawyers and editors who worked with him. He was also an extraordinarily cherished companion of his jurisprudential adversary, the late arch-liberal, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, his longtime colleague on both the Supreme Court and the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

What was it, then, about Scalia’s life and career up to the point of his confirmation that made for greatness? The critical biographies of Scalia suggest he became a justice because of his cynical and relentless ambition, and through a disingenuousness enabling him to please the right people at the right time. But Rosen, while acknowledging that Scalia had predicted to a chum in 1959 that he would eventually ascend to the Supreme Court, rejects the malicious insinuations of his progressive biographers.

Rosen’s Scalia is, simply stated, a man of principle, destiny, and phenomenal talent, a talent which blossomed through a rigorous and classical Jesuit secondary education at the then-military-oriented St. Xavier High School in Manhattan, through undergraduate study at the then still prevailingly Jesuit Georgetown University, and at the then still rigorous Harvard Law School, where he earned membership in the then still highly selective Harvard Law Review.

Talent alone isn’t enough to propel one to prominence, however, or to cause one to become an exemplar of a nation’s traditional values. Ambition, discipline, inspiration, discernment, luck, and faith may also be prerequisites, and Scalia had all of those as well. He was confirmed to the Supreme Court by a vote of 98-to-0 after many years of exemplary government service. This fortuity arose in part because he was the first of an influential Italian-American voting bloc ever to be nominated. It also helped that his nomination came while the Republicans still controlled the Senate and before rifts over judicial ideology split America’s two political parties. His confirmation also came before the debacle of October 1987, when Robert Bork as a conservative jurist failed to win Senate confirmation as a Supreme Court justice.

The felicitous love of a good woman figured clearly in Scalia’s life as well. His brilliant, personable, and lovely spouse, Maureen, managed their nine-child household. In an example of his legendary wit, when asked why he loved children so much, Scalia said it was not that he loved children but that he loved his wife.

Love, fecundity, and talent still aren’t enough for judicial greatness, however. If I were pressed to sum up the genius of American traditional conservative jurisprudence, I’d quote an earlier justice, Samuel Chase, who stated once to an 1803 Baltimore grand jury that there could be no order without law, no law without morality, and no morality without religion. Even if he never quoted Chase, Scalia appears to have embodied his dictum. Chase’s ideas are antithetical to the prevailing postmodern, secular ethos in the legal academy and, until recently, on the Supreme Court.

Instead, the philosophy of the liberal, pre-Trump Court’s majority was encapsulated in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s infamous “mystery passage,” in the Court’s now-overruled decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). This passage, which Scalia disparaged as the “sweet mystery of life passage,” reads:

At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Belief about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under the compulsion of the state.

Contrary to this succinct statement of liberal philosophy, individuals don’t define the universe or form their personalities all by themselves; they draw on thousands of years of civilization and culture. It is staggering that Kennedy as a justice of the United States Supreme Court could so misunderstand not only our tradition of integrating law with morality and religion but, indeed, the very psychological essence of human nature. But he was not alone: the legal philosophy of individualism, individual self-fulfillment, and radical autonomy outlined in Kennedy’s “mystery passage” has been dominant in the legal profession. Scalia’s greatness is manifested most clearly by his ability to buck the prevailing wisdom and completely repudiate Kennedy’s dubious mantra.

Just as the followers of Jesus found that their beliefs were a stumbling block to the Jews and folly to the Greeks, so Scalia’s beliefs were often ridiculed by his peers. Scalia’s contemporary and the most-cited legal scholar of his time, Appeals Court judge and University of Chicago law professor Richard Posner, dismissed Scalia as being among a group of “mediocrities” on the Supreme Court and as a naïf for believing, as a traditional Catholic, in the Devil. Rosen’s narrative presents a man who would occasionally describe himself in his speeches as a “fool for Christ,” and one, it seems, who was called by a higher power to sit on our highest temporal bench.

My former colleague at Northwestern University, Steven Calabresi, has pulled out all the stops and declared Scalia the greatest justice ever, greater even than virtually everyone’s favorite, Chief Justice John Marshall. Calabresi bases his assessment on Scalia’s Supreme Court work. We’ll have to wait for Rosen’s second volume to see if he agrees. Nevertheless, this book is a good first step in countering Scalia’s previous biographers who cast his career, as Rosen puts it, “not as the product of a lifetime of integrity and work powered by Nino’s genius, Maureen’s sacrifice, and their shared Catholicism, but rather as a triumph of cynical, careerist cunning.”

Rosen’s thorough research and sparkling prose elegantly explode that disparaging assessment. Now that the conservative majority on the Court, several of whom have acknowledged their debt to Scalia, has set about in earnest reversing the Court’s prior jurisprudential errors in the areas of race, religion, and abortion, we may soon understand the full legacy and influence of this American judicial giant.

Leave a Reply