“Nobility is the symbol of mind.”

—Walter Bagehot

In times of texting and sexting, Twittering and wittering, there is something positively antediluvian about epistolary collections—a whiff of fountain pens and headed notepaper, morocco-topped escritoires in long-windowed drawing rooms looking out over lawns studded with cedars and peacocks. Such fleeting evocations are lent depth and body when the letters in question have passed between lifelong friends Deborah Devonshire (now 89), last of the Mitford girls and chatelaine of Chatsworth, and Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor (94), war hero and gentleman-chronicler of an interwar, largely vanished, traditional Europe with which he lived on unusually intimate terms.

Leigh Fermor’s dangerously unsettling account of his peregrinations between 1933 and 1939 (in A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water—a long-deferred third volume is hoped for anxiously by legions of Leigh Fermorians) evokes a Europe that was even then anachronistic and which has since been almost entirely swept away by war and communism, or gnawed away by the worms of globalism. Portents were present to this observant walker (at least in retrospect—Gifts was published in 1977 and Woods and the Water in 1986) as he tramped solitarily from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople, an 18-year-old romantic, amateur historian, folklorist, and philologist, carrying in his rucksack a few letters of introduction, The Oxford Book of English Verse, and Horace’s Odes. He noted flambeaux-toting SA processions in Germany, and everywhere encroaching suburbanization and industrialization, improving transport and communications, fading folk memories, shrinking estates, shriveling patrimonies, crumbling chateaux—rumors everywhere of rationalization and reordering, dissent and diminution.

But there was time for him to sample Europe almost as if he had been a medieval traveler—in all its centuries-accreted color, ruins and runes, relicts and survivals, folk tales and prejudices, arcane wisdom and archaic dialects, intricately quartered coats of arms, unbuilt horizons, unmechanized agriculture, moonlit highways, hostels and Schlösser, white cathedrals and forlorn wayside shrines, churls and countesses, leprosy and libraries, wolves in the hills and giant catfish swarming in dark Danubian depths.

His evocation of an eclipsed Europe in those sometimes showy but perennially piquant books long ago made him a literary figurehead for nostalgists and would-be Wandervögels. Subsequent adventures have only augmented his status. Max Hastings observed in 2004 that Leigh Fermor was a man who “consciously sought Byronic experience.” This may be why, in 1935, he rode with royalist cavalry putting down a republican uprising in Macedonia, and in 1944 abducted a German general and smuggled him across Crete while pursued by whole Wehrmacht divisions (which latter exploit formed the basis of the 1957 film Ill Met by Moonlight). He spent months in French monasteries searching for spiritual enlightenment (recorded in A Time To Keep Silence), climbed and delved in South America (Three Letters From the Andes), tried earnestly to understand the piled-up nonsense of voodoo (The Traveller’s Tree), and wrote a lurid novel about an island’s extirpation (The Violins of Saint-Jacques). Philhellene nonpareil, he went on to write acclaimed books on Greece (Mani in 1958 and Roumeli in 1966) and build a house for himself and his wife, Joan (she died in 2003), on the Peloponnese at the southernmost tip of mainland Europe.

Mani contains the perfect Leigh Fermor passage—the ouzo-fueled “Byzantium Restored,” a pattern-book reverie, but one rooted in reality, lush and learned, suffused with longing and full of the poetry of proper nouns, and a passage that incidentally might now be dismissed by many as “Islamophobia.” (Elsewhere, Leigh Fermor explicitly bemoans the Turkish presence in Europe.) He has escaped this particular censure, although he has had a few pursed-lip critics, such as the Times Literary Supplement’s Mary Beard, who, in 2005, criticized his “laddish tales,” “blokeish tone,” “intricate and outdated disquisitions,” and disdain for mass tourism.

His In Tearing Haste correspondent is equally beguiling. It is not just that Deborah Devonshire is a duchess, with all that dust-mote-filled word connotes, inhabiting a Wodehousian ambience of great houses and garden parties, Labradors and Purdeys, Old Masters and Gloucester Old Spots, but also because she, the last of six gilded sisters (and one brother) who alternately graced and scandalized British gossip columns from the 1920’s onward, possesses all the Mitford directness and panache.

She is very different from, but also strangely like, her siblings—Nancy (1904-73), socialist, biographer, and author of Love in a Cold Climate; Pamela (1907-94), the quietest, called “the rural Mitford” by her admirer John Betjeman; Thomas (1909-45), a fascist sympathizer who refused to fight Germany but died in action against the Japanese; Diana (1910-2003), who married Sir Oswald Mosley; Unity (1914-48), a Hitlerite who tried to commit suicide upon the outbreak of war; and Jessica (1917-96), a communist who eloped to Spain during the Spanish Civil War and later became involved with the U.S. civil-rights movement, and steadfastly refused to speak to Diana in later life. Deborah’s only foray into politics was as a supporter of the bland Social Democratic Party in the 1980’s. She certainly did not share Unity’s adoration of Hitler, whom they both met in 1937; she informed an amused Daily Telegraph journalist in 2007 that she would much rather have chatted with her musical idol Elvis Presley.

Deborah, fundamentally practical and outdoorsy, might have been content to have been a second “rural Mitford,” but her marriage to one of Britain’s leading aristocrats (Andrew, the 11th duke of Devonshire, who died in 2004) has ensured that she has been a participant in many of the great public events and private dinners of the period covered by these letters (1954-2007). She has also been instrumental in saving Chatsworth, one of England’s most remarkable houses, from financial difficulties through tireless writing and merchandising—even operating a cash register in the estate’s gift shop.

Her and Leigh Fermor’s remembrances of some of the places, personalities, and events of those decades, which saw Britain turn from imperial power to E.U. province—Fairest Isle to Cool Britannia, workshop of the world to hedge-fund heaven, and Anglo-Celtic to multiracial—are fascinating because their authors know (or knew) “everyone” and understand the way Britain operates (or used to operate). Although essentially apolitical and sometimes even seemingly slight, these exchanges lend proportion, depth, and texture to the frequently told, but often superficial, saga of prolonged decline management.

“Debo’s” letters to “Paddy” (generally shorter than his to her) are a-brim with astute, arch observations on royals, prime ministers (Harold Macmillan was a relative by marriage), presidents (she sat beside JFK during his inauguration), artists, writers, musicians, sculptors, academics, designers—as well as a bucolic cast of hunters, farmers, pig breeders, butchers, and gardeners, even horses and chickens. She writes economically but to great effect. As Leigh Fermor noted in the Daily Telegraph in 2000, “She writes with ease and speed, and wonders what all the fuss is about”—her facility, a source of wonderment to a notoriously painstaking writer, luring him often into capering verse and cartoons, revealing an unexpected impishness.

Her comments are often hilarious. Jackie Kennedy seems to her “a queer fish. Her face is one of the oddest I ever saw. It is put together in a very wild way.” About the “Troubles” in Ireland, she writes, “I do love [the Irish] but I wish they’d stop shooting people’s knees. It’s such a horrid trick.” She recalls a very elderly friend who spends her dotage “doing the three Rs—Reading and Remembering Rogering.” Sometimes she makes penetrating points in an understated way, summing up trends and types in devastating phrases, such as when she writes of the Queen Mother’s funeral:

What a poke in the eye for the MEDIA that all those people queued night and day in the freezing wind to see the lying in state . . . we had a wonderful view of everything. Bang opposite that wretched little Prime Minster & the frightful Cherie. Prescott looks like a bare-knuckle fighter of Sackville Glove fame from the East End.

At other times, and increasingly as “the FOULNESS of old age” strikes down family and friends, the letters become “unbearable memories of the olden days.” For example, on the death of Diana Mosley—for many, a monster, but for Deborah, a beloved sister—she remarks,

It is so odd to have lost someone who was always there. The childhood cry of the seventh, straggling to keep up on stubby legs, of WAIT FOR ME, lives with me. She couldn’t.

Leigh Fermor is more political. In between typically dazzling descriptions of his latest exploits, he winces at the tedious “booming” of Simone Weil and occasionally comes out with things like “The present government obviously plans to quietly [sic] strangle English history in all its aspects.”

These letters (perfectly edited and annotated by Diana Mosley’s daughter-in-law, and including a necessary glossary of nicknames) are not a history nor even a diary, but an enlightening account of how two twitchingly alert, highly cultured people reacted and related to a maelstrom of eccentric and brilliant relatives and friends and, beyond them, to revolutionary social upheaval.

Their letters are a window into a vanishing ambience—what Richard Davenport-Hines called “a lost world of glamour, intelligence and personal scruples.” The world the two remember and regret was a small but significant planet, with a shared style, filled with in-laws and in-jokes, with common experiences and tastes, lightly sitting authority and noblesse oblige; its revolving cast of strong personalities viewed against a taken-for-granted cultural backdrop that gave a context to the players and grounded them in a time and place. Even “non-U” interlopers tried to be “U,” ditching serviette in favor of napkin and eliminating toilet for loo, while a certain grocer’s daughter from Grantham thought it necessary to exchange her flat Midlands tones for a strangulated variant of Received Pronunciation. (These days, if Daily Mail headlines can be relied upon, RP may sometimes be an actual drawback in some careers.)

That star so searingly recalled to life in this collection has gone supernova and is exploding indefinitely outward, its elegant cool architecture of class and control dynamited by death duties (inheritance taxes) and democracy. Its constantly changing, but curiously consistent, leadership cadre has now been almost entirely superseded by a “new aristocracy” of career politicians, celebrities, and oligarchs—a group that is looser, less rooted, less substantial, and as gauche ideologically as it is socially.

There are still generals, masters of foxhounds, clubmen, aesthetes, and Old Etonians (David Cameron, Boris Johnson, and George Osborne are all OEs), but they are no longer the default power in the land and have little context or corporate personality. The kind of houses lived in by Deborah and aspired to by Leigh Fermor are mostly now beautiful shells, with roped-off walkways along which tourists troop respectfully but bemusedly. Meanwhile, the Elizabeth Frinks have metamorphosed into Damien Hirsts, the Maurice Bowras into Terry Eagletons, the John Betjemans into Benjamin Zephaniahs, and the Benjamin Brittens into Britney Spearses.

“Dr Oblivion comes to see me a bit too often,” Deborah repines in 2004. That fell practitioner has already laid low most of her classy contemporaries, leaving the field open to artists who employ used tampons in their “installations,” winners of TV reality shows, surgically “enhanced” models, and highly paid politicians who use taxpayers’ money to pay for nonexistent mortgages and £1.50 bath plugs. This is not to say that there are not many cultured and elegant people left in England; there are (including Deborah’s children and grandchildren), but they are outnumbered, outgunned, and outflanked by the massed forces of Tedium and Ugliness. What is left behind as the high cultural tide recedes is mud, and a scrabbling mass of bores and drabs fighting for a piece of overripe pie.

Sir Patrick once recalled how, during his youthful journey across Europe, he might sleep one night in a hayrick and the next in a chateau: “I suddenly found myself in some tremendous castle with banners flying and horses galore.” Modern European adventurers are more likely to bed down in chain hotels with mints on the pillow, the banners and horses available only on DVD. We have all been impoverished and diminished.

But despite what has happened to the Old Continent, and the drawbacks of postwar politicians, the knight and the duchess have at least discharged their duty, bequeathing us noble literature and a great English estate still defying England’s debasement. They have also left us in these letters a memento of a mellower modus vivendi that in some ways is still with us (not least in the persons of these correspondents), but which in other ways has vanished as completely as the England of Emma.

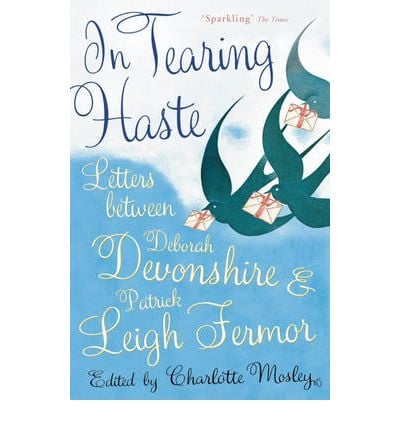

[In Tearing Haste: Letters Between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor, edited by Charlotte Mosley (London: John Murray) 416 pp., £25]

Leave a Reply