In 1988, I wrote in a review in these pages, “If there is any young historian out there who wants to know where the cutting edge is in American historical understanding, it is . . . the new and coming field of Northern history.” Complicity is one of a half-dozen or more books published in the past few years that have fulfilled my prophecy about the direction of new research. (Others that might be mentioned are Susan-Mary Grant’s North Over South and Joan Pope Melish’s Disowning Slavery.)

Actually, I did not prophesy at all, but merely said what was obvious to anyone who was thinking about American history, rather than, in the normal professorial way, thinking about how to hitch a ride on the prevailing fashions in historiography.

The authors of Complicity are three Hart-ford, Connecticut, newspersons who, in the course of delving into their state’s history, discovered all sorts of (to them) shocking things. There were slaves in Connecticut! There were even (gasp!) plantations in Connecticut as terrible as those in the South (shudder!). New Englanders participated in the slave trade and the profits of slavery. Northerners of the 18th and 19th centuries were white supremacists. Northerners continued, even after slavery, to exploit black people from afar—for instance, Connecticut’s famous piano manufacturing depended on ivory brutally extracted from the Belgian Congo.

There is really nothing about any of this that should be surprising. The authors’ gee-whiz attitude toward what ought to be common knowledge is testimony to the power of the American mythology of the Virtuous Nation. All evil is located in the South, requiring Americans (the North) to cross the Potomac now and then to stomp on the evildoers threatening to contaminate pure and shining America. The power of the mythology also draws upon a childishly simplistic view of human affairs, painfully evident in our empire’s foreign policy as we write. Real life (and, thus, history) is more complicated than that: For instance, the authors tell the story of the Mississippi slaveholders and public officials who conscientiously returned to their Northern homes free black people who had been kidnapped by Yankees for sale.

Actually, the authors have only glimpsed the tip of the iceberg. It will take many more books to tell aspects of the truth that they have not yet discovered. Most of the Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut signers of the Declaration of Independence were slaveholders, like their Southern colleagues. Massachusetts had the first formal slave code. When young John C. Calhoun of South Carolina went to college in New Haven, Connecticut, in the early 1800’s, he did not move from the land of slavery to the land of freedom. Most well-to-do families there owned at least a few black people. (And they still talked a lot about states’ rights, too.) Emancipation in the North was gradual and resulted in little improvement in the lives of the emancipated. Some of our authors’ Connecticut slaveholders moved operations to Louisiana sugar plantations before emancipation took effect, and New Englanders were always big investors there.

The foreign slave trade, far more brutal and sanguinary than the Southern plantation slavery of the late antebellum era, was, so far as Americans were concerned, a New England enterprise. After the importation of slaves to the United States was outlawed in 1808, Yankees remained for another half-century significantly invested in the profitable business of transporting Africans to Cuba and Brazil (not to mention the Chinese opium trade). Another of those monkey wrenches that reality throws into conveniently imagined history: Southern public officials and naval officers worked to shut down the illegal slave trade, whereas Northern public opinion protected the traders, usually men from prominent families, when they were caught. Even during and after the Civil War, New Englanders of the finest and most progressive families continued to own lucrative slave plantations in Cuba. (Young historians, take note.)

The American public has seemed of late to have some desire for a closer look at the mythology of our unique virtue and innocence, with well-selling books that question the painted and perfumed image of Father Abraham and his war against the Union. But there is still a long way to go before the unearned Treasury of Virtue (as Robert Penn Warren called it) gathered around emancipation ceases to distort Americans’ perception of themselves. (I assume that the study of history ought to make us wiser rather than more self-righteous.) As Frederick Douglass pointed out, any benefits that accrued to black people from the Civil War and Reconstruction were not the result of benevolence but incidental to the interests of Northern whites. Tocqueville observed that Southerners exhibited less race hatred than Northerners. New England’s greatest sage, Emerson, opposed slavery because he thought it contaminated whites. Deprived of the protection of slavery, the blacks would die off and become as extinct as the dodo. Freed of contaminating blacks and contaminated Southerners, America would achieve her destiny to be a pure and shining New England writ large, the vanguard of humanity’s upward march.

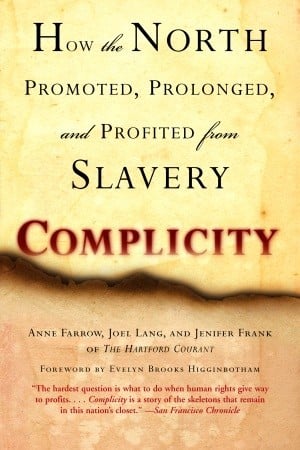

[Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited From Slavery, by Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jennifer Frank (New York: Ballantine Books) 269 pp., $25.95]

Leave a Reply