There’s no analysis to speak of in Bill Minutaglio’s and Steven L. Davis’s account of life and events in the city—Dallas—that much of the world came to hate after the Kennedy assassination. There is instead chronological recitation: this person, that person; words, deeds, threats, accusations, pleas, apologies, gestures; an amassing and piling up of facts, carefully researched, carefully winnowed, and selected for their effects on readers wondering for one reason or another about the most extensively chronicled event since World War II.

The mythology of the Kennedy assassination is by now set in concrete: a City of Hate, dominated by hatemongers such as H.L. Hunt, Gen. Edwin Walker, and the publisher of the Dallas Morning News, facilitated through its hatred the murder of a president. Oh, it wasn’t, you know, that Hunt and the others actually wanted Kennedy dead. Nevertheless, the shrillness of their views and their language made inevitable, more or less, the shots that ended Kennedy’s life. The facts, on Minutaglio’s and Davis’s showing, speak for themselves. This happened, that happened. One, two, three. Post hoc ergo propter hoc. Isn’t that enough?

Actually, no; it isn’t. Recitation of facts—even undeniable facts—gets you so far and no further. The question always becomes, in the end, whose facts? Arranged in what order, and with what purpose in mind? Historians once knew this, back before their acclimation to the fashionable faculty liberalism of the day, which tends to assume the wickedness of pre-contemporary social orders.

Liberal, conservative—one might as well get down to cases. The Kennedy assassination is the ultimate—in a certain sense the initiatory—liberal-conservative question. To buy into the well-established mythology of the assassination is to understand the political right in America, and particularly in Dallas 1963, as unhinged and out of control. In a scholarly paper delivered the month of the assassination, Richard Hofstadter linked modern conservatism with old-style anti-Catholicism and anti-Masonry. Feelings of loss and dispossession impelled the modern right wing, said Hofstadter, quoting the liberal sociologist Daniel Bell, and adding, “[T]he modern radical right finds conspiracy to be betrayal from on high.” Well!—who is higher than a U.S. president?

And so in Minutaglio’s and Davis’s recounting, radical right-wingers such as the slightly unbalanced Edwin A. Walker come vividly to the fore. General Walker, strenuously anticommunist commander of the 24th Infantry Division in Europe, brings his convictions and alliances to Dallas, turning up the fire beneath the city’s warmly bubbling anticommunism. The Dallas Morning News (I worked there for 29 years, before retiring in 2001) flays communism and socialism with powerful effect—and doesn’t care, editorially speaking, either for Kennedy or for his policies. The John Birch Society is active there, along with the Minutemen and an ad hoc group called the National Indignation Committee, which hates and fears the United Nations. Sometimes activism outruns common sense and just plain manners, as when conservative women swarm menacingly around Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson in 1960. Another mob, similarly constituted, boos and harasses U.N. ambassador Adlai Stevenson. There also figure in the story low-level activists whom no one now remembers: Larrie Schmidt, Frank McGehee, Robert Surrey—bit players in the enveloping tragedy.

We find ourselves, through the authors’ ministrations, living in a kind of moral twilight, where right and wrong merge indistinguishably. A large, important city’s very buildings and landmarks bend menacingly, mysteriously above the heads of ordinary people. And speaking of ordinary people: You find none in Dallas 1963. Everybody’s a little nuts—save, to be sure, two civil-rights figures, Juanita Craft and H. Rhett James, along with the merchant prince Stanley Marcus. These watch in disgusted fascination as the cancer of hate spreads.

The authors have a thing about the late Confederacy and its surviving relics, physical ones especially, in Dallas. They make continual references to local statues of Confederate heroes. It’s essential, apparently, that we know the parent company of the Dallas Morning News was founded by an ex-Confederate general, and that a large Confederate monument stands near the Municipal Auditorium. The effect calculated by the authors, one suspects, is the sinking of local culture as a whole in the controversies of the lost, remote past. No wonder, perhaps, that the racial integration of the public schools, initiated on September 6, 1961, has been neither swift nor enthusiastic in Dallas, with all those nostalgic Confederate descendants hanging around, recalling the good old days of separate drinking fountains.

The privilege of the cataloger is to catalog what he wishes us to admire or turn from in disgust. Minutaglio and Davis have exercised that privilege to the full. They have stacked the deck, to put it another way. What a place, this Dallas! What a lot of screwballs, or, at best, backward-lookers of no special intelligence—the same picture that liberals have painted since November 22, 1963. No wonder the authors keep their faces straight and lips generally buttoned as they guide readers past the moral boneyard. A look around tells all.

Depending on what one means by “all.” The stark, bare simplicity of the story the authors seem intent on telling—conservatives bad, liberals lovable—leaves no time for making much of the genuinely warm and friendly welcome the President received on the streets of Dallas. What was the matter—huh? Hadn’t the cheering throngs been listening attentively to General Walker? Nor, more tellingly, do Minutaglio and Davis open up the story of the local business establishment, whose commercial acumen and native good sense were the prime factors in Dallas’s rise as a great city. There are fleeting and semicynical references to the belief of top businessmen that civility serves general purposes better than flamboyant flaunting.

The Dallas business establishment, which included both Stanley Marcus and Dallas News publisher Edward M. Dealey, an outspoken critic of Kennedy, not only ran the city back then but ran it with a strong streak of civic consciousness. The establishment, for instance, procured the integration of Dallas schools and restaurants alike for purposes possibly—for the authors of Dallas 1963—less connected to sweet liberal reason than to concern for peace and the profit motive. The establishment was conservative and prudent—not nearly radical enough for the age that was coming. But it did its best, and its best, most of the time, was quite good.

The age that was coming, and might be said to have arrived in Dallas in November 1963, unfolded and flapped its wings in coming months. The authors, having told their story, disappear from the stage. The story goes on without them—in ways complex, confounding, and not entirely to the purpose of impeaching the good will of Dallas conservatives in general. Political discourse of all kinds was taking on darker hues.

The Dallas crowd that jeered Stevenson had nothing like the effect of the still-remembered TV spot on behalf of Lyndon Johnson, running for a full term in 1964, suggesting that Barry Goldwater was open to the prospect of obliterating daisy-picking little girls in a nuclear war. At the University of California-Berkeley, in 1965, left-wing students tried to shut down the place in an exercise of their imputed rights. What we know now as “The Sixties” was upon us. Destruction swirled all about.

The dreaded right—the right that supposedly had slain John Kennedy—was quiescent on the whole. The rioting and ruction of the mid-to-late 60’s began on the left. How come? Was the “paranoid style” in politics more prominent, more identifiable on the left than on the right? I would have appreciated from Minutaglio and Davis, given their commitment to the trite-and-true City of Hate narrative, a forward glance at the trouble. With some analysis? Some sifting of realities in quest of truth?

Did all the nuts of the day dwell on the right end of the spectrum and worship General Walker? Surely not. And if not, how do we explain the general nuttiness of the time? Is it possible at all to write about Dallas in 1963 as if the city were on some South Seas island, remote from burgeoning concerns that arose throughout the West in those times? The authors evince no interest in such topics, for all their seeming relevance to the question of how a horror like the Kennedy assassination could have happened. It puts me in mind of Frederic March in Inherit the Wind, released as a movie around the time Kennedy was elected. Playing the role of William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes Trial, March insists, under grilling by Spencer Tracy, “I don’t think about things I don’t think about.” (Oh—and by the way! Lee Harvey Oswald, the nearly undisputed assassin of the President, was a Marxist, professedly sympathetic to the Castro regime in Cuba. How do we account for that as we visit, under expert guidance, the city of right-wing hate?)

A man should write the book he wants to write. If the two men who produced Dallas 1963 wanted merely to tell once again the tired saga of Dallas’s collective guilt for the Kennedy assassination, let us concede them that privilege. Their research has been diligent, their focus intent. Too intent, I fear, to give their volume the centrality they may desire for it in anniversary accounts of the assassination.

The stacked deck from which they have dealt their cards sits there visible to all: Deuces and jokers for the old, angry Dallas, aces for the discerning few able to discern its bleak conservative soul. Take a hand, if that’s your thing.

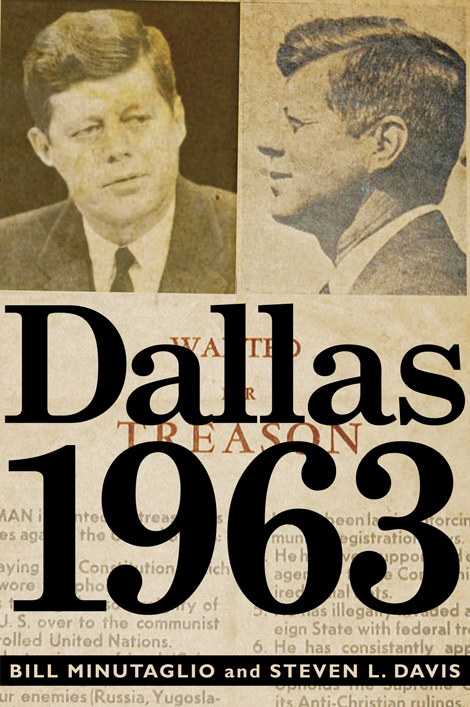

[Dallas 1963, by Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis (New York and Boston: Twelve) 371 pp., $28.00]

Leave a Reply