Faulkner the Southerner and the

Continuity of Southern Letters

by James Everett Kibler, Jr.

Abbeville Institute Press

338 pp., $39.95

Early in Faulkner the Southerner James Everett Kibler, Jr. notes that “Southern ways have to do with pressing terra firma. Barefoot is a good way to approach Faulkner.” This evocative advice goes to the heart of what Kibler attempts to accomplish in his semi-biographical study of the greatest of American novelists.

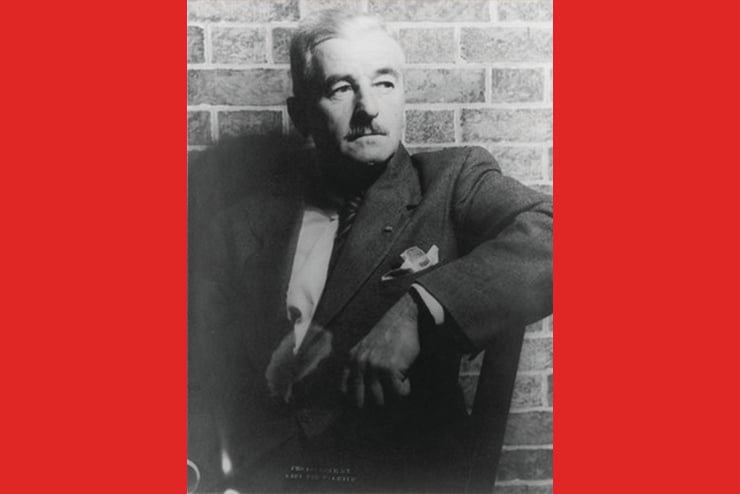

Over the decades since William Faulkner received the Nobel Prize, the study of his work has become an academic industry, and the flood of critical tomes combing through virtually every aspect of the Mississippian’s fictional world shows no signs of receding as university presses around the globe exploit the prestige of the Faulkner “brand.” Yet far too few authors know even the first thing about the American South as a lived experience.

Instead of making genuine attempts to understand the world that bred Faulkner’s genius, such critics—like demented contortionists—subject it to any number of insufferable theoretical analyses. This is the sort of criticism that goes over well at academic conferences but offers us nothing germane, nothing that draws us closer to the pathos (and comedy!) of blood and soil that is the Southern habitus. Kibler, in contrast, has made an admirable effort to remedy this problem—to restore Faulker to Yoknapatawpha, his fictional homeland, where the ancestral fires still burn.

One crucial point readers and students of Faulkner’s work frequently miss is how deeply embedded it was in an oral tradition. Southern culture is a storytelling culture. Southerners love to talk! But this is not merely an addiction to idle chitchat. “Otherners” who travel in the South often complain that it takes twice as long to get through the checkout line at the Piggly Wiggly because shoppers eagerly engage in conversation with those ahead of or behind them or with the cashiers. More importantly, Southerners love to sit around on their porches and trade yarns, weaving together like women at a quilting bee their shared histories—a kind of spontaneous myth-making, if you will. Most Southern writers, having grown up in this way, write in the same vein of emotional engagement. As Kibler notes, Faulkner never wrote with detachment and never stood “aloof from his subject [or characters].” Instead, he addressed the reader face-to-face with a tall bourbon toddy in his hand.

Faulkner, commenting on this quality in Southern writers, once stated that storytelling and oratory are “our heritage.” This was true of the great Irish writers, too. Southern critic Cleanth Brooks noted that for both Yeats and Faulkner there “was available an oral tradition—a fountain of living speech” to draw from. Even Faulkner’s most challenging “modernist” novels, like The Sound and the Fury, should first be savored not as intellectual constructs to be deciphered, but as patterns of sound and rhythm that convey an underlying emotional significance that is ultimately chthonic in origin—that is, of the hidden recesses of the earth.

Also crucial in understanding Faulkner as he would have wished to be understood is grasping the overwhelming importance of blood ties and a sense of place for Southerners. The Old Dominion’s landed gentry was once called a “cousinage,” a tightly intertwined network of relations resulting from many generations of intermarriage. What was true of Virginia was also true of most of the South. According to Kibler, the “history of the South is the history of … families and their connections to one another.” Indeed, “the South itself is a close collection of families.” Richard Weaver’s notion of “social bond individualism” was inspired by this recognition. In Faulkner, individuals are almost always tightly woven into webs of kinship, and those who are not are always, in some sense, castaways, adrift in an alien world.

“Faulkner’s ideal man, “writes Kibler, “is never the isolato, the lone wolf.” Nor is he a “cosmopolitan” figure. He is always, for better or worse, rooted in a particular place. Reading Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man, Southerners of Faulkner’s generation would have been puzzled, even a little horrified that such an alienated figure as Dostoyevsky’s protagonist could exist: “Where are [his] family?” they might ask. Even broken or dysfunctional families in Faulkner’s world were better than no family at all. One learned to live with them, not to discard them and run off to a city full of strangers, which would be a kind of spiritual suicide.

Elaborating on Faulkner’s sense of the primacy of place, Kibler suggests that the “oral tradition of passing on a piety for places” is common in Celtic cultures or those descended from such cultures, like millions of Southern families. He writes, “For one of the duties of the Celtic bard was to sing songs venerating the local by attaching story, people, and events to a particular locale in order to humanize the landscape.” Faulkner lived out his life in Mississippi, but like so many young American writers of the 1920s he, too, sojourned to Paris in search of inspiration. Instead, he found only homesickness.

Returning to the South, he settled for a spell in New Orleans, where he encountered the writer Sherwood Anderson, who urged the young Faulkner to “write about that little postage stamp of land in Northern Mississippi where he was born and raised.” Faulkner took that advice, and within a year, he had begun to reimagine his postage stamp—calling it Yoknapatawpha County. In time, he purchased a decrepit antebellum home not far from Oxford and restored it himself, naming it Rowan Oak.

Those who know their Faulkner will recall the sharp contrast between the novelist’s loving restoration of a Greek Revival home hallowed by time and generations of use and the hellish house erected by his demonic character Thomas Sutpen in Absalom, Absalom!, who, as Kibler notes, was placed “against a backdrop of the stumps of giant trees in a pocked and barren landscape denuded by saw mills.” The “doomed” house was the very antithesis of the graceful, columned structures that were still a common part of the Southern landscape in Faulkner’s day. The symbolic importance of these structures for Faulkner is evident in one of his most celebrated short stories, “Barn Burning,” in which the mansion of Col. DeSpain inspires in the young protagonist Sarty Snopes a “surge of joy.”

It must be emphasized, however, that Faulkner’s reverence for the Southern past was never misted over with sentimentality. Far from it. He well understood that humankind has always been, and always will be, marked by the sign of Cain. The tragedy of the Southern past is always in view in Faulkner’s work. Man is fallen, but not without some glimmering of the possibility of divine grace—hence the need for humility and an awareness of the misbegotten pride that poisons all our endeavors.

It was owing, in part, to his religious convictions that Faulkner was highly skeptical of the modern project and its infatuation with progress. In Faulkner’s work, one will not find anything suggesting an affinity for the “modern, liberal-progressive premise that man is by nature essentially good and perfectible by utopian means.” He was not impressed by technological idealism. Like his Charleston predecessor in the 19th century, William Gilmore Simms, he did not believe that technological improvement somehow brought about “moral improvement.” Kibler demonstrates that Faulkner, like the Nashville Agrarians, was frequently a critic of “machine culture,” a culture inextricably tied to the mythos of progress. Speaking of that tragic conflict we call the Civil War, he once stated that “the machine that defeated [the Northerner’s] enemy was a Frankenstein which, once the Southern armies were consumed …” turned on the North and “transformed it into a baronage based on the slavery of machines.”

Against the overbearing tyranny of the machine age, Faulkner upheld the moral necessity of memory and endurance. Only memory frees us of the captivity of the present, which is a kind of blindness that forecloses upon any moral perspective not in conformity to the demands of technological progress. Modern writers, all too often and paradoxically, have pandered to “the eternal gratification of the present” and thus produced little more than “glandular writing”—writing without a past or, for that matter, a future.

Closely related to the importance of memory is the power of endurance, a theme perennial in Southern literature and everywhere in Faulkner. It is accepting hardship as part of the providential order, out of both pride and humility. As M. E. Bradford argued some years back, pride in this context is not of the satanic or hubristic variety but involves the courage to overcome cowardice and fear of the human condition.

Was Faulkner a conservative? In Kibler’s view, the answer is an unequivocal yes. Nevertheless, as he makes clear, the novelist was always wary and even disdainful of the flag-waving patriotism too often passing for conservatism in both Faulkner’s time and our own. During the Cold War, he condemned the “cacophony of terror and conciliation and compromise babbling … the loud and empty words which we have emasculated of all meaning whatever—freedom, democracy, patriotism….”

Aside from a brief period during the Civil Rights era, Faulkner was not a political animal. Nevertheless, his philosophical stance certainly had political implications. Kibler writes, “What is clear is that Faulkner’s world view was not urban progressive-socialist-man-in-the-mass … but generally conservative (in the old root sense of ‘conserve’), rural, traditional, individual, personal and concrete.” This is correct, though it must be added that the “individual” stripped of family, community, and locality is merely a cipher—the perfect fodder for the creeping totalitarianism that was Faulkner’s greatest political fear.

Those who have yet to venture into Yoknapatawpha country will find Kibler a reliable guide. Those who have read and enjoyed Faulkner already will find much here to flesh out and enhance their understanding of one of our most elusive and profound novelists.

Leave a Reply