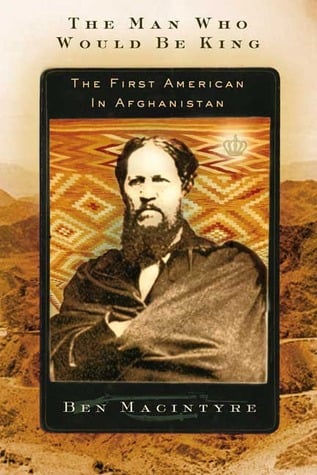

The Man Who Would Be King: The First American in Afghanistan

by Ben Macintyre

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 351 pp., $25.00

In recent memory, when we think of Afghanistan, we recall perhaps first the struggle of the CIA-backed mujahideen guerillas against the Soviet invaders. The Soviets lost 50,000 men and eventually their power, but in their (our?) victory(?), the Afghans lost a million people and such unity as they had. The transition through civil war to the Taliban is a bit fuzzy, though the impression of “blowback” is unmistakable. More recently, we think of videotape of bombs falling on rocks and the bizarre displacement of Afghanistan by Iraq in American bombsights.

The sense of what Yogi Berra called “déjà vu all over again” is rather disquieting. America’s repetition of British imperial entanglements offers many points of ironic reflection, not the least of which are the willfully misleading tone of our national rhetoric and the mordant formulation “Wolfowitz of Arabia.” Of course, we all relate to the surreal politics of our time as best we can. I, in considering these matters, think of attending a garden party more than three decades ago at which I heard Jerry Bremer (our recently dethroned proconsul in Iraq) declare that Afghanistan, his first diplomatic posting, had many strategic options. Indeed it did.

British journalist and author Ben Mac-intyre has had his own experience of Afghanistan and has gone on to actualize and substantiate the imaginative vibrations and resonances he sensed there in 1989. One echo was of Rudyard Kipling’s story “The Man Who Would Be King,” written in 1888 when the author was but 23 years old. Macintyre calls Kipling’s story “thrilling stuff, a story of freelance imperialism in which a white man becomes a powerful potentate in a distant land, but also a cautionary tale of colonial hubris, ending in disaster.” He is right as far as he goes, but I think there is more to say about Kipling’s great tale in its own right. As for the historical genesis of that fiction, Macintyre has made a tremendous contribution—or, rather, two contributions—to our understanding of the colonial imagination.

Macintyre came across hostile accounts of Josiah Harlan (1799-1871)—American Quaker and Freemason from Chester County, Pennsylvania, adventurer, quack, mercenary, and mountebank—in colonial British sources. The bulk of Harlan’s papers were thought to have been lost in a fire in 1929, but Macintyre found his journals and other materials, misplaced in a local library. Harlan had boasted in 1842 that he had once been the prince of Ghor or Ghoree, a realm high in the Hindu Kush, under a secret treaty with its ruler. This boast was assumed either to be untrue or to be without foundation, but Macintyre found the document itself, justifying Harlan’s claim to exotic royalty.

But there, yellow with age at the bottom of the box, was a document, written in Persian and stamped with an intricately beautiful oval seal, a treaty, 170 years old, forged between an Afghan prince and the man who would be king.

Macintyre’s second contribution is hard to define exactly, though easy to sense. I do not know whether it is his powers of expression or the vision and empathy that are expressed that lend his account such distinction. However that may be, his book is a whopping good read, whether he is accounting for all the senses in which Alexander the Great is such an imposing figure in history, in Afghanistan, in Harlan’s imagination, and in Kipling’s tale; or taking us through Harlan’s campaign of 1838-9. Harlan led a division of the Kabul army of Dost Mohammed Khan as a punitive expedition against Murad Beg, khan of Kunduz, Uzbek warlord and slave trader, over the Hindu Kush, marching in the footsteps of Alexander. With nearly 4,000 men, 2,000 horses, 400 camels, and a bull elephant, Harlan sallied forth to cross mountain passes of nearly 16,000 feet. As he said, with the air too thin for flight, “large storks could be seen labouring up the steep passes on foot.” The result of his expedition was both a glorious beginning and an ignominious end. Though he was secret royalty, he could not exploit the opportunity, for, as luck would have it, the results of his expedition were swept away by the British invasion of Afghanistan. Of the 15,000 people of the British incursion, only one survived. Harlan returned to America and obscurity.

The story of Harlan is not quite justified altogether for its own sake; Macintyre connects it firmly to Kipling’s story. One stone that he has left unturned is a more precise attack on the great tale itself—a miniaturization of epic, romance, and tragedy, a triumph of the vernacular, and an object lesson in the craft of embedded or displaced narrative. Even Conrad’s Heart of Darkness owes something to it; and we must be reminded that Conrad’s character Lord Jim is based on James Brooke, the White Rajah of Sarawak, who is alluded to in Kipling’s text. Another rock to be turned over, in my opinion, is to examine the phenomenon of the “bloody Quaker.” Was Harlan so exceptional after all? As Martin Green has pointed out, the bloody Quaker is a staple of imperial romance, in Defoe’s Captain Singleton, as well as in Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales, in Robert Montgomery Bird’s Nick of the Woods, and Melville’s Moby-Dick.

Finally, I must add one further reflection. The excitement of Macintyre’s narrative, regarding both Harlan and his own exploration, rather masks the truth that his account is fundamentally an inspired work of creative scholarship. What would have happened if the story had been written by an abstracted academic, hag-ridden with postmodern clichés about Harlan’s sexuality, political incorrectness, misogyny, and orientalism? The tale would have had no teller and would have died as a monograph. Instead, a vivid and shrewd imaginative engagement has found its own best expression in this brilliant recital.

Leave a Reply