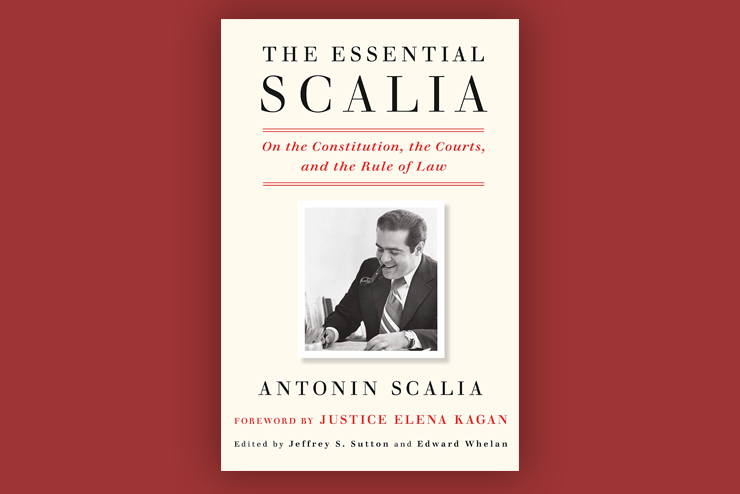

The Essential Scalia: On the Constitution, the Courts, and the Rule of Law; By Antonin Scalia; Edited by Jeffrey S. Sutton and Edward Whelan; Foreword by Justice Elena Kagan; Crown Forum; 368 pp., $35.00

Steven Calabresi, one of the founders of the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, maintains that Antonin Scalia was the greatest justice ever to sit on the Supreme Court. Calabresi, an outstanding Constitutional scholar, thought Scalia surpassed even Chief Justice John Marshall, the usual consensus pick for America’s greatest justice.

That Scalia was a magnificent and incisive legal mind almost no fair-minded observer would dispute. Moreover, he was admired even by those with whom he most deeply disagreed, including Justice Elena Kagan, who writes the foreword to this volume of his collected writings, and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Scalia was indeed an “essential” jurist, primarily because he was for decades the most forceful critic of a Court which has overreached its proper scope.

In her opening statement at her confirmation hearings, Amy Coney Barrett said that she adhered to the same judicial philosophy as Scalia, and that his reasoning had shaped her own. She’s not alone in this. Many prominent conservative jurists were influenced by Scalia—Calabresi clerked for him, as did the two editors of this volume. In Scalia’s judicial philosophy, as Barrett put it:

Courts have a vital responsibility to enforce the rule of law, which is critical to a free society. But courts are not designed to solve every problem or right every wrong in our public life. The policy decisions and value judgments of government must be made by the political branches elected by and accountable to the people. The public should not expect courts to do so, and courts should not try.

That modest view of the judicial role makes Scalia the odd man out, as it has not been popular in the legal academy, in the Democratic Party, or on the Supreme Court bench. The dominant view, since the time of Chief Justice Earl Warren, has been that we have a “living Constitution,” one which changes in accordance with “the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

According to adherents of the “living Constitution,” it is the job of justices to discern those “evolving standards” and interpret the Constitution congruently. That’s what the Supreme Court did when it found in the Constitution a right for women to attend state-sponsored military academies, a right to terminate pregnancies, a right to be free from prayer at public school graduations, a right to engage in consensual homosexual conduct, and a right to gay marriage.

This, according to Scalia, was unmitigated hubris, and a usurpation of the most fundamental right of the American people to self-government. Scalia’s attempt to bring jurisprudence back to where it belonged centered on two basic ideas: “textualism” and “originalism.” Textualism is a strategy of statutory interpretation that reads legislation in its “plain meaning,” not in light of extraneous remarks on the floor of Congress or in committee reports, or to effectuate a favored policy of the judge. Originalism is a philosophy of constitutional interpretation akin to what used to be called “strict construction”—that is, giving the words of that document only the meaning that the framers and ratifiers intended.

Scalia also believed that the Supreme Court’s habit of finding competing policies in the Constitution (or in a statute), and weighing their various strengths to produce a desired policy result was fundamentally misconceived, and that such “balancing” was the job of legislators, not judges.

To state Scalia’s views is to reveal that they were no more than common sense—a rare commodity of late. His modest notions of the judicial role subjected him to ridicule in the academy, which idealized the role of justices as law and policy makers.

Scalia fought back with religious zeal. He became the nation’s first “celebrity justice,” was a popular lecturer at law schools and professional associations, and was an extraordinarily gifted writer, particularly in his dissenting opinions. “No one has ever written quite like Nino, and no one ever will,” Kagan writes in the foreword. “Line after line, it is captivating stuff, full of wit, dash, and verve.”

Scalia fought back with religious zeal. He became the nation’s first “celebrity justice,” was a popular lecturer at law schools and professional associations, and was an extraordinarily gifted writer, particularly in his dissenting opinions. “No one has ever written quite like Nino, and no one ever will,” Kagan writes in the foreword. “Line after line, it is captivating stuff, full of wit, dash, and verve.”

Bryan Garner, the country’s leading legal lexicographer, and co-author with Scalia of a splendid guide to reading law, has called this collection “the best one-volume compendium of the Justice’s erudition and wit,” and proclaimed that “It won’t be bested.” He’s probably correct, although one of the editors, Edward Whelan, did edit two other anthologies, Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived (2017) and On Faith (2019), both of which go deeper into their subjects than does this volume.

Still, what is included here does reveal what impressed Kagan about Scalia’s writing. The excerpts are full of Scalia’s learned allusions to the Old Testament, Shakespeare, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Sherlock Holmes, Daddy Warbucks, George Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut, and The Lone Ranger—a diverse literary arsenal few others could deploy.

Even so, the real value of the collection is to introduce the reader to Scalia’s judicial opinions. Reading law is not often thrilling. The terms are arcane, the prose is usually deadened, and the subject matter is of little interest except to specialists. This book’s two editors—Jeffrey S. Sutton, a distinguished federal appellate judge, and Whelan, a wise pundit and the president of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, have excised the legalese and offered excellent introductions to each reading, splendidly putting the cases and speeches in context.

The materials are organized according to four topics: explaining textualism and originalism; contrasting these with the views of the advocates of the so-called living Constitution; an explanation of Scalia’s sensible approach to jurisprudence; and a review of agency actions, the least accessible section, but still important because taming the administrative state is a crucial political problem.

For this reviewer, the most important part of the book is the presentation of Scalia’s opinions on the three perennially divisive Constitutional law issues: race, religion, and abortion. No other topics reveal so clearly Scalia’s greatness.

In a time when we are told by the left that our society is “systemically racist,” that slavery was our original sin, and that from this we can never be redeemed short of substantial redistribution and reparation, Scalia offers a bracing rebuttal. Rejecting race-based “affirmative action,” Scalia argued in 1979 that

the racist concept of restorative justice of which [affirmative action] is merely the concrete expression, is fundamentally contrary to the principles that govern, and should govern, our society. I owe no man anything, nor he me, because of the blood that flows in our veins.

On this point Scalia hewed consistently to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s admonition about individual character. It is difficult enough to remediate past discrimination, but that is comparatively easy by contrast to the challenge of “eradicating…the source of those effects, which is the tendency…to classify and judge men and women on the basis of their country of origin or the color of their skin.”

On the matter of religion, Scalia was one with the founders in his understanding of the fearsome potential of sectarian belief to generate civil strife. And yet he and they also knew that nothing is so inclined to foster among religious believers of various faiths a mutual tolerance than voluntarily praying together “to the God whom they all worship and seek.”

He never wavered in his view that the so-called “wall of separation” between Church and State had been raised too high. In Lee v. Weisman (1992), for example, he argued in his dissenting opinion that, as long as prayers delivered at public school graduation ceremonies are nonsectarian, they should be allowed and encouraged.

Finally, Scalia regarded the Court’s decisions on abortion as the premier instance of its hubris in trying to solve problems for which it was supremely unequipped. He worried over what was lost when the moral dilemma represented by abortion was removed from “the political forum that gives all participants, even the losers, the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight.”

By imposing “a rigid national rule instead of allowing for regional differences, the Court merely prolongs and intensifies the anguish,” Scalia wrote. He stated on numerous occasions that the Court should vacate arenas of contention where it “had no right to be, and where we do neither ourselves nor the country any good by remaining.”

Scalia is gone, but he lives on in the hearts of Justice Barrett and his many other admirers. This laudable anthology makes clear why that is the case.

Leave a Reply