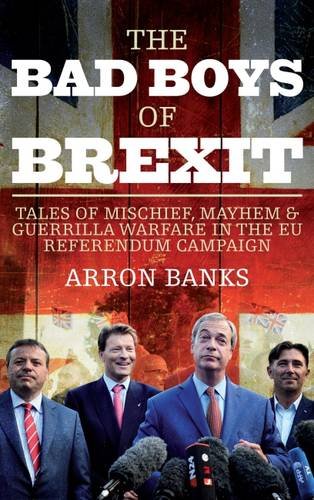

Arron Banks looks out proudly and pugnaciously from the cover of Bad Boys of Brexit like a character in a Hogarth engraving, flanking the equally Hogarthian Nigel Farage in a photo taken as Farage faced the globe’s agog media on the auspicious morning of June 24, 2016. The four men pictured—Banks, Farage, Richard Tice, and Andrew Wigmore—look rumpled, tired, and unshaven, but deeply happy, a natural reaction from the adrenalized, unexpected victors of one of the bitterest battles in recent British political history. For Farage, Brexit was the culmination of 25 years of unstinting campaigning, years filled with controversy and contumely—but he would probably never have had that moment’s supreme satisfaction had it not been for the men around him, perhaps especially the stocky, dark-haired man to his right who appears to be trying to suppress a gargantuan laugh.

Banks, 51, is John Bullishly English: class conscious, combative, commonsensical, generous, impatient, opinionated, slightly philistine, sturdily patriotic, tough, and vigorous, just the phenotype Hogarth envisioned living in Beer Street. He had only known Farage for two years, and their first meeting did not go very smoothly, but from the outset he recognized Farage’s special qualities and realized that working with him would be mutually beneficial, and potentially world-altering. When not engaged in building up his insurance empire, Banks, a youthful Thatcherite, had observed despondingly the drift of European policy and rued Conservative Euroskeptics’ inability or unwillingness to engage. So when Farage asked him to donate £100,000, he was happy to oblige. When Banks saw Foreign Secretary William Hague on TV dismissing the donation as being from “someone we haven’t heard of,” he rang Farage back to increase the amount to one million pounds. Battle had been joined—against ineffective Tories as much as ideological Eurocrats.

Banks became closely involved with UKIP but was dismayed to find it “hopelessly dysfunctional and ill-prepared for campaigning,” with more than its fair quotient of eccentric supporters like John Mappin of Mappin & Webb, who once regaled Banks with a description of his “super-powered brain control system” that would swing the referendum their way. And there were others he thought much worse, especially Douglas Carswell, the ex-Tory who became UKIP’s only MP and, in late March, became an independent. (Often, Banks prefers principled leftists to Conservatives.) Banks became fiercely protective of Farage, likening himself and Andrew Wigmore to

loyal guard dogs that are more than a little feral and unpredictable when we’re off the lead. [Farage] loves us and we love him, but occasionally we bite him on the backside and he responds with a sharp kick.

Farage was fortunate indeed to have assembled such good-hearted (and deep-pocketed) stalwarts to found, in July 2015, and lead the Brexit umbrella group “The Know,” which was relaunched as Leave.EU the following September. Banks loaned six million pounds and helped raise a further eleven, Wigmore was director of communications, and Tice (“Mr. Collegiate”) also gave generously and soothed egos bruised by his brusquer colleagues. Provoked by an anti-Brexit intervention from the IMF’s Christine Lagarde, Banks growls, “it’s time to audit the elites”—and this is just what Leave.EU did. Big politics, big business, big institutions, and big opinion were all fair game, targeted eventually by a campaign staff of 90 using big data, with a 60-strong call center signing up supporters and donors, all from an industrial estate off the M5 motorway beside a Premier Inn—an unlikely HQ for a nationalist resistance movement. “If BBC producers aren’t spluttering organic muesli over their breakfast tables every morning we won’t be doing our job,” he notes—revealing much about his personality and Leave.EU’s tactics, not to mention the neoliberal right’s fondness for cliché and its bizarre prejudice against environmental responsibility.

The American political campaign advocacy Goddard Gunster were taken on as advisors, and the campaign even enlisted the TV hypnotist Paul McKenna as a consultant. On the eve of the referendum, Banks calculated that Leave.EU had issued 20 million leaflets and 19 million letters, amassed millions of video views and one million social-media followers, and reached some 15 million people every week—many of whom would have been ignored or unmoved by Vote Leave, the anodyne, officially designated Brexit campaign group fronted by Boris Johnson and Michael Gove.

Banks was brought up partly in South Africa, which gave him a taste for frontier pastimes like diamond-mining, drinking, fishing, off-roading, and shooting. He was sent to a private school in England and beguiled these obviously duller times through sundry “high-spirited activities,” eventually being expelled for antics including selling stolen lead. He calmed down sufficiently to move into the British insurance industry, first at Lloyds, before he established his own vastly lucrative enterprises—also a bank, a diamond-mining firm, and a leisure business. He is married to a Russian, has five children, and owns two Gloucestershire mansions. His combativeness and purse pride are meliorated by charitable commitments, honesty, and wistful tastes—for Banks, “If” is a “great poem,” while To the Manor Born is ideal viewing.

Bad Boys of Brexit was pieced together after the campaign from Banks’s emails, text messages, and daily jottings, and his own “fallible memory.” It took just six weeks to assemble the text with the help of Isabel Oakeshott, and although they did an excellent job their speed shows at times; a few individuals are mentioned without the reader being told who they are, while there are references to arguments Leave.EU had with NASA and the sports journalist Gary Lineker without any background having been sketched in. Irritatingly, the book has no index but instead the characteristic note, “If you’re looking for the index, there isn’t one. Deliberately. Read the bloody book!” The decision to forfeit an index may have been made partly to save production time, but it’s mostly designed to prevent politicos index-surfing for mentions of themselves and skipping the rest of the text, as some are wont to do. This is a nuisance for a reviewer who wants to cross-check some fact, and it will lessen the book’s academic value. Nonetheless, Bad Boys rings true, and when Banks claims he was “careful to avoid hindsight,” generally we can believe him. His memory may well be “fallible” and selective—but then, whose is not? In any event, the result is engrossing, funny, insightful, and revealing of how modern British politics works (or doesn’t work).

Banks uses sniper rounds as well as grapeshot, alternately hitting marks precisely and peppering the enemy. Politicos who do read Bad Boys in search of their names will likely wish they hadn’t bothered, as his opinion of them is usually withering. But then they probably know that already, since Banks always fought in the open, to the chagrin not just of the consensual Tice but even of the combative Farage. Douglas Carswell is “autistic with a touch of mental illness”; Tory MP Peter Bone resembles “a lost extra from The Addams Family”; as for another Tory MP, Teresa Coffey, “let’s just say they didn’t invent the phrase ‘wake up and smell the coffee’ with this lady in mind.” On the left, Neil Kinnock is the “bellend of all bellends,” while François Hollande “has the expression of a man who’s been presented with a cassoulet when he ordered duck à l’orange.”

Elephant-gun ammunition is reserved for Vote Leave’s principals, Dominic Cummings and Matthew Elliott. Banks dislikes them personally—Cummings is a “shyster,” and Banks issues Elliott with a writ for defamation after he hears Elliott has been calling him a racist and homophobe—but most of all he despairs of their messaging. Their expensively produced, eminently forgettable Brexit: The Movie is “a free-market wet dream” featuring “weirdo, dead-eyed academics,” and he labels their eye-catching claim of how an independent U.K. would save £350 million every week “a blatant lie” that undermines the Brexit case. Their overreliance on 80’s figures like Nigel Lawson and David Owen reminds him of “grave robbing.” He feels they are too close to the SW1 elite, too set in their tactics, to be reliable:

The stars of the Vote Leave show have been dining out on Euroscepticism for years, preaching to a congregation of pinstriped bores who will lap up any glib Shakespeare quote thrown their way with a chorus of smug guffaws.

Actually, Banks is unfair to Vote Leave, which did deliver a more middle-class, middle-of-the-road demographic less amenable to Leave.EU’s emphases. A Brexit campaign fronted by Nigel Farage would probably not have succeeded; the charisma of Boris Johnson, the intelligence of Michael Gove, and the prestige of their high offices were vital assurances for many. But there were unnecessary tensions between the groups, and these were chiefly caused by Vote Leave (who also snubbed several attempts at truces).

Seen in retrospect, these “friendly fire” incidents seem amusing, like the predictable media smears—Banks and Wigmore presented as supposed tax dodgers owing to their links with the British Virgin Islands and Belize, the resurfacing of 25-year-old tabloid tales about Wigmore’s supposed sex life, not to mention endless allegations of the usual “phobias.” Of course at the time these smears were anything but amusing, and any one of them could have derailed the whole endeavor. Nevertheless, Banks clearly enjoyed the bare-knuckle sport, such as when he responded to criticisms from the Vatican about Brexit erecting barriers by tweeting a picture of the forbiddingly circumvallate Vatican. When David Beckham spoke against Brexit, Leave.EU published with relish anti-E.U. comments made in 1996 by his wife, Victoria, and laughed off threats of a lawsuit. When Farage was omitted from a BBC television debate, Leave.EU published the email addresses and mobile-phone numbers of the leaders of Vote Leave, Douglas Carswell, the producer, and the email of the BBC director general. A House of Commons select committee before which Leave.EU leaders testified descended into a shambles when it confused Richard Tice with an unrelated namesake who had died in 1910. Banks was half-amused, half-infuriated when Unionists hesitated to sign the Ulster cross-party Brexit declaration because the ink looked green, and agreed to do so only when shown that it appeared golden in certain lights. Whatever was thrown at them, Banks and the others threw it back with added interest, fueled by testosterone and lubricated by copious quantities of alcohol.

Banks’s pleasure was (and is) basically boyish, taken from shocking sensitivities simply because they were (and are) sensitivities. After Leave.EU issued a video about migrant violence, Banks metaphorically rubbed his hands together: “We’ve got our biggest gasp of outrage yet from the leftie media, and we’re savoring it.” Those gasps grew life-threatening on the morning of June 16, when Leave.EU unveiled a poster showing a column of refugees tramping along a European road under the heading “Breaking Point.” The poster brought frantic denunciations, and Farage was already on edge when, in the afternoon, Labour MP Jo Cox, a Remainer and refugee-settlement advocate, was murdered by a man shouting “Britain first!” Leave.EU suspended campaigning immediately, but this did not stop Remainers from making cheap conceptual connections.

The highly charged offensive reached its end under suitable skies as a vast electrical storm flashed across Britain, causing flooding in the south. Almost every expert assumed Brexit’s cause was lost. At lunch on Referendum Day, Farage said, “We’re going to lose. I can feel it in my waters,” and he conceded defeat to a Sky journalist. Banks empathized—“Years of political disappointment had conditioned him . . . he didn’t dare to believe it could be different this time”—but he for one believed the thing would be won, based on a Leave.EU poll. As the night wore on, the drinks went down and the results came in, everything altered, and Banks and Wigmore floated out of the wake-turned-party at dawn, half-drunk and clutching yet more champagne, to see the Thames and Westminster in fragile light, in a celebratory cacophony of taxi and truck horns, and an elderly man trying to get as much money as he could out of a cash machine because he feared a run on the banks. And then they were all on College Green, SW1, blinking at the first day of a new era, grouped around Farage in proprietorial hope as similar auxiliaries once clustered around Hereward the Wake, Wat Tyler, Jack Cade, or John Wilkes..

That day is already passing into folklore, becoming part of an insular mythos, and now . . . now what, indeed, for Britain, and especially this energized man? “I’ve got a feeling my time in politics has only just begun,” Banks writes. The Brexit vote was only a “halfhearted revolution,” and he does not trust the May government to deliver the controlled-border “Singapore on steroids” he seeks. In January, he launched Westmonster.com, a Breitbart-inspired news site described as “pro-Brexit, pro-Farage, pro-Trump, anti-establishment, anti-open borders, anti-corporatism,” and in March, he announced the foundation of a new party, the Patriotic Alliance. It will be interesting to see whether he can sustain interest in Westmonster’s more abstract kind of activism, while the prospects of the Patriotic Alliance probably depend on whether Nigel Farage can be inveigled back into everyday politics. The only thing certain is, as Donald Trump joked to Farage when the Banks group met with him, “Those boys look like trouble. I’d keep an eye on them.”

[The Bad Boys of Brexit: Tales of Mischief, Mayhem and Guerrilla Warfare in the E.U. Referendum Campaign, by Arron Banks (London: Biteback Publishing) 365 pp., £18.99

Leave a Reply