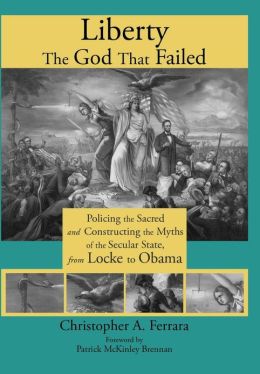

Liberty: The God That Failed is Christopher Ferrara’s second 90-caliber salvo against liberalism, left and right. His first, The Church and the Libertarian: A Defense of the Catholic Church’s Teaching on Man, Economy, and State, smashed the anti-Christian dogma of Austrian economics. This 699-page tome goes further. It will send the neocons into the corner to gnash teeth with their leftist cousins, and a few paleocons may join the brooding bunch.

It attacks, after all, the premise of this country’s Enlightenment political order. Ferrara’s point is this: American and Western “liberty” is rooted in a false conception of man and the state and the relationship of one to the other. The lurch toward “liberty”—for Ferrara’s purpose, beginning with Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, continuing into the late 18th century, and culminating in the American Revolution—continued the Protestant war against the Catholic Church and the Catholic conception of man, his political order, and the end to which they are ordained. The pre-Hobbesian conception of government was this: Man has an eternal soul, and the role of the state is to help man toward his natural end, which is life with God in Heaven. Hobbes and Locke, Ferrara writes, undermined that Greco-Catholic polity, supplanting it with a wholly new one: The only role for government is to secure a man’s life and property rights. Beyond that, government should do nothing. As Ferrara writes, even the British Protestants of Locke’s time, who were still attached to at least the dying remnant of Christendom, thought he was a crackpot.

Locke offered something “radically broken from Western tradition”—the notion that government and religion must be completely separate and operate in “different spheres of influence.” In particular, Ferrara writes, the Church of Rome would no longer play a role as the “conscience of the state,” as She always had. But neither would Her Protestant offshoots. According to the American philosophes, the Church was guilty of perpetrating unspeakable violence and tyranny, and She must therefore be removed from any role in government. But Ferrara rightly observes that it has been atheist and/or democratically elected tyrants who have perpetrated the most shocking violence in human history, starting with two million dead during the revolution that bestowed “liberty, equality, and fraternity” upon the eldest daughter of the Church. The Vatican neither erased Dresden nor vaporized Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Democracy did.

The Declaration of Independence is a “veritable transcript” of Lockean ideas, and the American secession from England was not, as modern neoconservatives want everyone to think, “conservative” and measured. It was radical. The “Christian” founders—as American evangelicals never cease calling them—had, following Locke, arrogated unto themselves a right unknown to Christendom: the right to revolution. They concocted a government uniquely divorced from the religion of the civilization that whelped them. That is hardly measured.

Revolutionist propaganda was specifically anti-Catholic. Of particular concern to the American agitators for revolution was the Quebec Act, which legalized the practice of Catholicism in Quebec. What “liberty” really meant, Ferrara writes, was freedom from “Romish superstition.” Revolutionary propaganda stoked fears that “Popish chains” would bind the minds of American colonists unless George III, suspected of mackerel-snapping sympathies, were successfully overturned. Ferrara marshals much evidence to demonstrate the anti-Catholic nature of the rebellion’s intellectual leaders. One instance of papal phobia concerned Samuel Adams, a failure at everything he tried except, like Lenin, inciting people to mob violence. When Patrick Carr, a mortally wounded participant in the mob attack on British soldiers that led to the Boston Massacre, admitted that the redcoats fired in self-defense, Adams smeared him as an “Irish papist.”

Ferrara spoils much of the American mythology we take in with our mother’s milk, not least that the colonists suffered under the yoke of an oppressive “tyrant” in George III. George Washington thought the Hanoverian a good king, and the colonists “beat back every unwanted measure except for the tea tax.” Yet tea was cheaper in the colonies than it was in London. Washington and Jefferson were wealthy men. As for taxation without representation, all Englishmen were taxed, but only “one in twenty,” as one source put it, was represented. And the notion that the justice of a tax depends upon representation is another of the “self-evident” truths for which neither Locke nor anyone else could find any support in history or tradition. What matters is not provenance but justice.

Propagandists preached the worship of liberty with idolatrous zeal, importuning colonists to dance around “Liberty Trees” and “Liberty Poles,” and woe to the “loyalist” who refused to participate in this sacrament. “Liberty” was a religion. Pamphleteers and orators spoke of it in pious tones.

Yankees won’t like Ferrara’s treatment of Honest Abe; neither will Southerners cotton to his claim that Confederate leaders pushed for secession to keep their slaves. Ferrara does not claim slavery caused the war, and he rightly notes that most fighting Southerners did not sally forth into Union canister and gunfire to perpetuate the “peculiar institution.” Likewise, Ferrara debunks the Northerners: The blue bellies did not march up Maryre’s Heights to end slavery, he says, but for Lincoln’s Union. But considering the more than 600,000 dead at the war’s end, he calls down a pox on both houses. In some sense, the casus belli is unimportant to his main point: Secession was rooted in the same ideology with which the colonies justified secession from Britain, liberty of the Lockean species. The Confederate Constitution was a “veritable clone of the government from which it had seceded,” and it did not include a proviso allowing secession. The South, he claims, was no more entitled to secede from the United States than the colonies were entitled to secede from Britain. There is no “right to revolution.”

Which brings him to the federal Constitution, Holy Writ among professional conservatives. That the states had a right to nullify federal laws, or that states’ rights prevailed over federal mandates, is nonsense. Conservatives ignore the Supremacy Clause:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.

The Framers did not intend for the states to possess the right to abrogate federal statutes or federal power, either through nullification or secession, at will. The Tenth Amendment does not supersede the Supremacy Clause. Quoting Kirkpatrick Sale, Ferrara notes that a powerful central government is what the Framers intended and what we have inherited. That is why the Antifederalists feared and opposed the Constitution.

The National Reform Association (NRA) sought to amend the Constitution to “indicate that this is a Christian nation.” A committee of the U.S. House of Representatives rejected the idea. Ferrara rightly notes that the NRA’s approach was “doomed to incoherence because of the Protestant principle of private judgement in matters of faith and morals” and the NRA’s “acceptance of the principle of majority rule.” After all, if the majority rules, then nothing can stop the majority from declaring that white is black or that right is wrong. But the NRA had the right idea. Without Christ as the ultimate King, without a moral law higher than that of the ballot box, anything goes. Ferrara calls Washington a “Masonic Stoic,” Jefferson an “Enlightened Infidel,” and Madison a “Religious Void.” As an unconfirmed nominal Episcopalian, Washington refused to kneel for prayer in his church and did not take communion. Jefferson expurgated Jesus’ miracles from his famous bible and refused to be a godfather to the children of Anglican friends because he would not profess belief in the Trinity. Like Washington, Madison was unconfirmed and refused to kneel in prayer. These men were not believing Christians. No wonder, Ferrara concludes, they crafted a Constitution ignoring the religion of “the people” they claimed to represent.

Ferrara might be charged with not being an historian, and not having approached his subject with sympathy for, or intimate knowledge of, the 18th- and 19th-century Americans of whom he writes; it might be argued that the history he does offer is rather a polemic, even a jeremiad. Yet Ferrara admits his purpose up front: It is to show what was wrong at the beginning, regardless of who the actors and stage managers of the time were.

Which brings us back to the author’s thesis: This country is what it is today—a society corrupted by abortion and sodomitic “marriage,” and a government that attacks practicing Christians—because the Founding Fathers excluded the Christian religion from its fundamental law. The only hope for true regeneration is the restoration of the Catholic Church to Her rightful place. Protestantism doesn’t suffice. Well-intentioned as the evangelicals are, their belief in private judgment in matters of faith and morals, and their readiness to cede moral questions to majority opinion, doom any attempt to reorder society along Christian lines. It is either all—meaning Catholicism—or nothing, meaning moral chaos.

Neither liberals nor conservatives will like this book. But it is still a book they need to read.

[Liberty: The God That Failed, by Christopher Ferrara (Tacoma, WA: Angelico Press) 699 pp., $36.95]

Leave a Reply