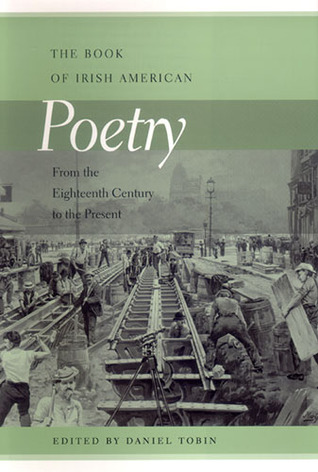

This handsome book, with its dust-jacket reproduction of Hughson Hawley’s Laying the Tracks at Broadway and 14th Street (ca. 1891), is unique in American anthology-making. While it has long been acknowledged that Irish American fiction and drama constitute what Charles Fanning called, in The Irish Voice in America, “a distinctive and complex literary heritage,” Irish American poetry has not received the same recognition, partly because of its simplicity and stock themes. That it should be examined is implicit in this undertaking. Daniel Tobin (who teaches at Emerson College) has revisited and redefined the subject, not by eliding the popular vein, but by going beyond it. The resulting collection shows how various and abundant the Irish American poetic lineage has been. The compilation is not, however, a canon but an essay (in the original sense of the term)—an undogmatic and pragmatic attempt to circumscribe the meaning of “Irish American” for literature and assess, collectively, the contributions so identified. Whether the diverse body of writing associated with this lineage constitutes a true literary tradition, sui generis, or is composed of several traditions, or is simply a gathering without being a whole may be for future critics to decide. In his Introduction, significantly titled “Irish American Poetry and the Question of Tradition,” Tobin concludes that his selections constitute “a testing ground rather than a canonical template for what it means to be Irish American.” The absence of a hyphen in “Irish American” is a marker of his position.

As Tobin’s approach suggests, the 215 poets, most represented by two or three samples each, are Irish American in varying senses and degrees. Some, such as Brian Coffey, belong, by citizenship or residence, chiefly to Ireland (not the United States) but have written extensively about this continent. Others started out in America but later settled in Ireland and became, as it were, American Irish. A few are not Hibernian at all but deal with Irish American matters. The most striking instance may be the black author Paul Laurence Dunbar, whose poem on John Boyle O’Reilly (the major 19th-century Irish American author, represented by nine pages here) depicts the Celts as a “generous race” and bears witness to their belief in freedom and the common aspirations of both oppressed groups. A similar example is Gwendolyn Brooks, whose “Bronzeville Woman in a Red Hat” portrays the unfortunate kitchen maid Patsy Houlihan and her black successor. Jewish writers Louis Simpson (creator of a figure named Tim Flanagan) and Alan Shapiro (author of a sequence on the potato famine) and the Pole Czesaw Miosz are likewise included.

The largest category is that of resident poets who are American-born of wholly or partly Irish or Scots-Irish ancestry, whether or not recent arrivals (some belong to the New Irish immigration), and who identify themselves as such. Many treat topics from the Irish American experience—their own or others’—or from the geography, history, and literature of Ireland. An Irish theme is not a requirement, however: Numerous selections have no explicit connection to the Irish but are included, nonetheless, as representative writing by those with whom the anthology deals.

Using a nautical metaphor, suggesting immigration to a far shore, Tobin has organized his material, by poets’ birthdates, into three titled parts: A Fluent Drift, Modern Tide, and Further Harbors. The first begins with George Berkeley (1685-1753), whose “Verses on the Prospect of Planting Arts and Learning in America” (with its famous line, “Westward the course of empire takes its way”) propose a golden vision for the New World. (“There shall be sung another golden age, / The rise of empire and of arts . . . ”) This part includes several major figures: Thoreau, Whitman, James Whitcomb Riley, Edwin Arlington Robinson. The selections are not necessarily well known; Whitman, for instance, is represented by his minor poem “Old Ireland.”

The second section, grouping poets born between 1873 and 1936, includes Robert Frost and Wallace Stevens along with John Gould Fletcher, Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore, Louis MacNeice, and other poets of stature. Many other names are familiar to connoisseurs of modern poetry: Phyllis McGinley, Theodore Roethke, Charles Olson, J.V. Cunningham, John Berryman, Randall Jarrell, Reed Whittemore, Hayden Carruth, A.R. Ammons, X.J. Kennedy, and Thomas Kinsella. Poets in the third part, whose birthdates run from 1937 to 1980, nearly three centuries after Bishop Berkeley’s birth, include, among many established figures, Brendan Galvin, Philip Dacey, Stephen Dunn, Billy Collins, R.T. Smith, and Paul Muldoon.

The compilation is rich in the connections now called “intertextual,” among topics, motifs, and even authors. Authorial connections appear in poems on O’Reilly by J.W. Riley as well as Dunbar; then, there is Robert Lowell’s strange poem for Eugene McCarthy (here in his own right), which begins, “I love you so. . . . Gone?” (I am inclined to believe that Lowell’s reputation, like that of Sylvia Plath, depends considerably on his well-publicized mental problems and melodramatic life.) “To Robinson Jeffers” by Miosz, Robert Creeley’s “For Ted Berrigan,” and Maura Stanton’s “Ode to Berryman” all deal explicitly with poets represented in the collection. Other poems mention great Irish figures not included here, such as Wilde, Yeats, and Beckett. These explicit evocations of predecessors are sometimes contrarian (Miosz on Jeffers), but usually fraternal. There are also many recurring thematic, metaphoric, geographic, and historical echoes, from Ireland and Irish history but also from New York and other centers of Irish immigration. There is something to being Irish or Irish American—even for those whose surnames indicate other ancestry. A few poets not eligible for this anthology might wish they were.

Although there is, of course, no particular Irish American form, poems that can be loosely classed as elegies and lamentations are very much in evidence. In other respects, these authors display a tremendous aesthetic range, in forms, tones, and diction, though the trend away from fixed forms and toward free ones is evident here, as in any anthology treating the same period. A number of 20th-century poetic groups are represented. For instance, a cluster of Beat poets may be identified, including Philip Whalen, and another from the confessional school, including John Berryman and Lowell. The New York School and the Black Mountain Poets likewise have representatives. There are a few New Formalists. Aesthetic modes do not preclude ethnic considerations; rather, they give different voices to them.

Politics constitute another axis along which certain poets can be grouped. Political and social aspects of immigration are a common concern. Themes from American history and a concern for justice recur at all periods. Thomas Branagan addressed the question of slavery, and O’Reilly wrote on the Battle of Fredericksburg; more recent poets famous for their political activism are Daniel Berrigan and McCarthy. In short, the anthology is nearly a cross-section of modern American poetry; while its contents are, in one sense or another, all Irish, characteristically American movements, forms, attitudes, and themes are visible throughout.

This book is a major literary and critical achievement. Notwithstanding the scholarly material—Introduction, Chronology, 20 pages of notes on the poems and authors, two bibliographies, and indices of titles and poets—it is basically a superb poetic treasury, just as suitable for one’s home collection as for research libraries. Its hundreds of poems, full of lyricism, though veined with Celtic melancholy and the sense of the tragic, constitute versions of an historical and cultural tradition of enormous importance to America and still vigorous, proving that Irish American culture is more than just a good pub or a St. Patrick’s Day parade. As Tobin observes, quoting T.S. Eliot, “Tradition is composed ‘not only of the pastness of the past but of its presence.’” In addition to making an outstanding contribution in its own right, the book suggests the viability of further literary categories beyond the well-recognized ones of Jewish American, black, and, now, Chicano. While it may prove impossible to delineate satisfactorily such strains in American letters as Italian, German, Slavic, French, and Scandinavian, further awareness of such presences, their features, and their geographical centers may be in order now, as a counterweight to tyrannical multiculturalism and an invitation to an authentic one.

[The Book of Irish American Poetry, edited by Daniel Tobin (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press) 925 pp., $65.00]

Leave a Reply