As a conservative undergraduate student during the early 1960’s, I spent many a long night engaged in animated political argument with a close friend whose supercharged IQ was exceeded only by his condescending manner. The fellow never tired of reminding me that, yes, there were a few responsible Republican public officials. He would always tick off a very short list of them, which routinely included such liberal GOP icons as Sen. Clifford Case of New Jersey, and, of course, Nelson Rockefeller. My friend summarily dismissed conservatives as denizens of the netherworld, characterizing them as either Southern bigots who believed that blacks, women, Roman Catholics, and Jews should be kept in their place, or as benighted boors who occupied the lower rungs of the evolutionary ladder.

Then, in 1964, a cantankerous Arizona senator confounded pundits and Republican leaders alike by capturing the GOP presidential nomination. Barry Goldwater’s sudden ascendance, and the national conservative movement that he helped set in motion, are the subject of Rick Perlstein’s provocative yet sympathetic book.

Rather than resorting to boilerplate explanations for Lyndon Johnson’s landslide victory, Perlstein concentrates on the shifting political landscape. He keelhauls the pundits for smugly dismissing Goldwater’s candidacy, citing their premature postmortem as “one of the most dramatic failures of discernment in the history of American journalism.” Two years later, he notes, “conservatives so dominated Congress that [LBJ] couldn’t even get a majority to appropriate money for rodent control in the slums.” The House Republican Caucus elected as chair of its policy committee John Rhodes, a Goldwater protege from Arizona. Moreover, ten new conservative Republican governors —most notably Ronald Reagan in California—won election. (Not bad for a conservative movement that had been written off as a mere political footnote by the so-called wise men after the 1964 election.) Perlstein reminds us of a growing national discontent with President John Kennedy in 1963 that caused more and more voters to reconsider whether he deserved reelection: increasing civil unrest combined with a rudderless foreign policy had prompted many to question Kennedy’s competence. More and more people began to clamor for a plainspoken leader who would change the political dialogue.

November 22, 1963, of course, altered the political landscape, and the hazy afterglow of Camelot lulled much of the country into nostalgic reveries about the fallen prince and what might have been had he lived to fulfill his destiny. Few recalled that Kennedy’s fateful Dallas trip was basically intended to help close the ever-widening political breach in the Deep South. President Johnson acknowledged the magnitude of that breach when, after signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he told his staff, “I think we just gave the South to the Republicans for your lifetime and mine.”

Perlstein also documents the merciless media mugging that Goldwater received from the moment he became the GOP presidential nominee and decamped from the Cow Palace in San Francisco. Magazines and newspapers that had formerly praised his forthrightness began to pummel him as a reckless political extremist. The normally GOP-friendly Saturday Evening Post reflected this sulfurous sentiment when it recommended his crushing defeat for the salvation of the party. Psychiatrists and psychologists were trotted out to question Goldwater’s sanity. The Democrats, under direction from Bill Movers, proved adept at character assassination, depicting Goldwater as a trigger-happy wild man who was itching for full-scale nuclear war in Vietnam.

Meantime, Goldwater’s many missteps played into the hands of his critics. Downright disdainful of the hoopla involved in running a national campaign, the reluctant candidate was far more comfortable articulating his philosophical differences with an overweening federal government. As a presidential candidate, Goldwater was too honest, stubbornly refusing to pander to his audiences. Instead, he inveighed against Social Security when addressing Florida retirees, assailed the Tennessee Valley Authority before the very folks who benefited from the federal project, condemned federal cotton subsidies in the presence of Southern cotton growers, and criticized a major defense contract to General Dynamics in Fort Worth, Texas, the home of the military-aircraft division of the company. Goldwater’s dislike of campaigning showed in his desultory rambling speeches, as in his response to supporters who kept chanting, “We want Barry”: “If you’ll shut up, you’ll get him.”

Perlstein claims that Goldwater’s biggest strategic blunder was jettisoning F. Clifton White, who was primarily responsible for the senator’s success in gaining the nomination. White’s command and control of supporters at the convention was masterful. Yet he was discarded soon thereafter in favor of such Goldwater confidantes as Denison Kitchel and Karl Hess, who were clearly beyond their depth.

Despite his several shortcomings, the candidate remained a straight-shooter. When Lee Edwards implored the senator to capitalize on his rugged Western persona, Goldwater shot back, “Lee, we’re not going to have that kind of crap on this campaign. This is going to be a campaign of principles, not of personalities. I don’t want that kind of Madison Avenue stuff, and if you try it, I will kick your ass out of this office.”

His opponent was not so scrupulous, allowing his operatives to suggest that Goldwater would savage Social Security, start World War III, roll back civil-rights laws, and otherwise unleash the forces of darkness upon the land. These horror stories were commonly accepted on college campuses, where this thoroughly decent man was routinely heckled as a hatemonger. Late in the campaign, I attended a Goldwater speech at Toledo University. No sooner had the senator begun to speak than he was showered with verbal abuse from the crowd. He had to cut short his remarks. Ronald Reagan, who campaigned for Goldwater, had far better crowd reactions. His ability to mesmerize an audience prompted ABC newsman Howard K. Smith to comment that Reagan had missed his calling: He should have gone into politics. (The fabled speech that Reagan delivered toward the campaign’s end prompted comparisons with William Jennings Bryan’s fiery “Cross of Gold” oration before the Democratic National Convention in 1896.)

Incidentally, my liberal Republican friend from college has become a staunch conservative. To paraphrase the lament of Goldwater voters four decades ago, those 27 million Americans turned out not to be wrong after all.

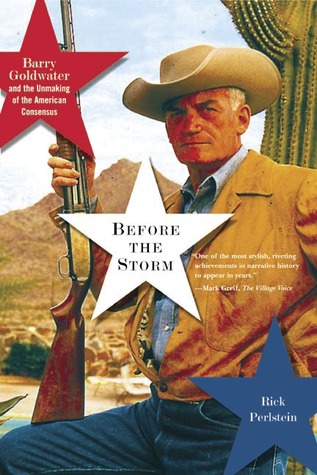

[Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus by Rick Perlstein (New York: Hill and Wang Publishers) 671 pp., $30.00]

Leave a Reply