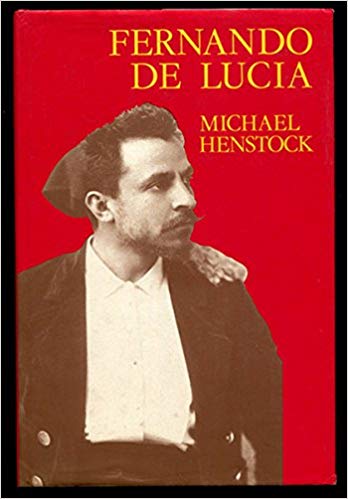

Memory and testimony have kept alive the reputation of Fernando de Lucia, and so have the four hundred recordings that tenor made between 1902 and 1921. His old discs- Gramophone and Typewriters, Fonotipias, and Phonotypes—are among the most fascinating of historical recordings. What they suggest about the man and his context has inspired Michael Henstock to go after his subject with a maximum of zeal. Though the performer’s art is evanescent, Henstock has done everything humanly possible to recreate the matrices of De Lucia’s career and even to impress his reconstructed sound upon the mind’s ear.

Henstock’s extensive researches—a labor of love if I’ve ever seen one—have resulted in an elaborately documented and even exhaustive account of a singer’s life. The survey of critical reactions to De Lucia’s performances cover three continents, three decades, and comments in Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, English, et cetera. Henstock builds his case systematically, showing how De Lucia formed his style upon those of three stars—Gayarre, Masini, and Stagno—and how he ascended to take their place as an internationally celebrated performer. The author is as precise as words allow in rendering subtleties of style and in leading the reader to understand De Lucia’s portamento, his mezza voce, and his sfumature—qualities that his recordings have preserved.

But he also sees Fernando de Lucia in the round. Singing exists in a social context—it is more than the production of pleasing sounds. So Henstock draws for us a picture of Naples, its society and landscape, the people and the culture. De Lucia was Neapolitan to the core, and his career grew with the exfoliation of Neapolitan song. Songs such as ‘O sole mio, Marechiare, Torna a Surriento, ‘O maTenariello, Occhi di fata, Aprile, and Mattinata belonged to De Lucia from the beginning, by complete identification. He sang them for his neighbors. He sang them for royalty. And he recorded them for us. De Lucia owned those songs—universally beloved by older generations—as Gigli and Schipa and Bergonzi were later to do.

But the focus of De Lucia’s career was operatic, and Henstock emphasizes his place in musical history, for his ascendancy corresponded with that of verismo. De Lucia was probably the greatest Turridu, the greatest Canio, and the greatest Don Jose that ever trod the boards. Of course he excelled as the Duke of Mantua and as Count Amalviva—he sang the bel canto roles beautifully and freely—and he showed a flair for comedy and even sang Lohengrin (!), but his best work on stage was in the new operas of Mascagni, Leoncavallo, and Puccini.

De Lucia’s prominence was such that he was instrumental in establishing the verismo operas in the repertory, and he was important in the history of Mascagni’s compositions after Cavalleria Rusticana. Henstock’s tireless exposition of the tangled relations of ambitious composers, autocratic conductors, proprietary publishers, scheming managers, and vulnerable singers is a rich portrayal of the music business in action. In addition, he shows us De Lucia’s colleagues, some of whom are today still regarded as the greatest of singers, just as they were when he sang with them: Patti, Plangon, and Battistini, to name but three.

And of course Henstock shows us Fernando de Lucia, who, though he treats him as a hero, he represents fairly and unflinchingly. The course of the great singer’s life was a glorious one, though it was tortured by what seems to have been a miserable marriage. De Lucia lived long enough to become a legend, to teach, and even to sing at the funeral of Caruso, the young lion whose style made his own seem quaint. De Lucia’s subtlety and grace were not to be cultivated as virtues in the modern period, though perhaps Henstock’s admirable book may help to turn the tide.

This book is a scholarly contribution to the history of music, of performance art, of theatrical history, and of Italian culture, as well as a deeply developed rendering of the decades before and after the turn of the century. Henstock’s life of De Lucia may not be for everyone, but it will certainly attract those individuals fascinated by its subject as well as by the broader context of vocal art and the history of opera. His book will also find its place on many a library shelf as a permanent reference and source.

But this has not been Henstock’s only service to the memory of Fernando de Lucia. Henstock has also been the compiler of an anthology of De Lucia’s recordings of Neapolitan songs, gathered in a two-CD set, “Fernando de Lucia,” Opal CDS 9845 (imported by KOCH International). Those discs contain over two hours of De Lucia’s singing, transcribed digitally at lower speeds than the 78 r.p.m. they have usually been played at. Henstock’s elaborate arguments for bringing down the speeds of antique acoustically recorded discs in order to pull the pitches down a half-tone are ones to be studied, their results to be considered. No one can doubt Henstock’s knowledge of the material or devotion to the task, though some have questioned not so much his logic as the aural product. I have found my ear adjusting to the Opal transcriptions, not least because they give me new access to the enchanting voice of Fernando de Lucia. Somewhere that great singer must be proud of what his champion has accomplished on his behalf

[Fernando de Lucia, Son of Naples: 1860-1925, by Michael E. Henstock (Portland: Amadeus Press) 555 pp., $45.00]

Leave a Reply