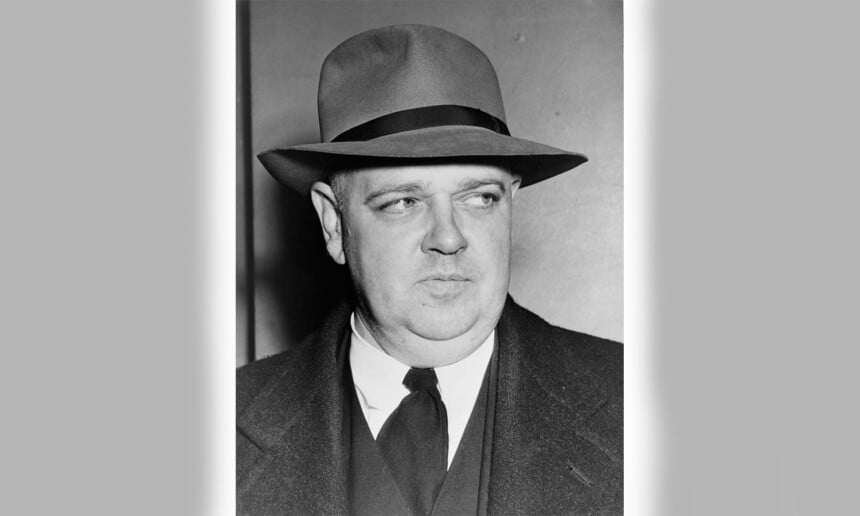

Perhaps the greatest American autobiography in both the quality of its writing and the import of its content is Whittaker Chambers’ Witness (1952). Sadly, it’s also one of the most neglected by the country’s leftist-dominated intelligentsia.

Witness describes Chambers’ winding path through the Communist underground in the 1920s and ’30s, from his Pennsylvania Quaker upbringing, through atheism and Marxism, and finally a return to a belief in God that led him to turn against his former associates and testify as the lead witness in the famous 1948 Hiss trials that launched the career of Richard Nixon.

Chambers details his life as a journalist and Time editor who had risen to become a high-level Soviet spy. He purloined U.S. government documents and led in the creation of espionage cells in New York and Washington, D.C., where he cultivated the now-famous Communist agents Alger Hiss at the State Department, and Harry Dexter White at Treasury. Both men were hugely influential in U.S. policy; Hiss was instrumental at the Yalta Conference and its pact between FDR, Roosevelt, and Stalin, and helped create the United Nations. White was a key figure in the Bretton Woods Conference and a creator of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The middle section of Chambers’ book reads like a spy novel, with safe houses, microfilm, dead drops, scheming fellow spies, and paranoid Russian agents. These fantastic elements of the narrative are tempered by Chambers’ honesty about the banality of spycraft. Lurid details aside, Chambers’ true genius is his keen insight into how philosophy motivates human behavior. This insight was shaped by the devastating effect of his brother’s loss of Christian faith that led to his subsequent suicide as a young man. Chambers shared his brother’s atheism but avoided his fate by throwing himself into Marxist ideology, which took on the form of a substitute religion for him and his fellow American communist brethren. A willingness to die for the cause united them, even to the point that many dutifully reported to Moscow to be purged.

After a decade in hiding, Chambers emerged to warn of the internal threat. In aiming for Communism he also hit something else: a “great socialist revolution, which, in the name of liberalism, spasmodically…but always in the same direction, has been inching its ice cap over the nation…”

—Edward Welsch

Image Credit: [Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons-Fred Palumbo, public domain]

Leave a Reply