“It’s a small, white, scored oval tablet.” A little pill stands between Florent-Claude Labrouste and his planned defenestration. It offers only a temporary reprieve from the meaninglessness of life. As the narrator of Michel Houellebecq’s latest novel assures us, Captorix:

provides no form of happiness, or even of real relief; its action is of a different kind: by transforming life into a sequence of formalities it allows you to fool yourself. On this basis, it helps people to live, or at least to not die—for a certain period of time. But death imposes itself in the end…

Not exactly beach reading.

In Serotonin, as in his other novels, Houellebecq writes of the benighted lives of the spiritually bereft. His characters are heirs of the Enlightenment, living vaporous lives among the metaphysical ruins of Western civilization. Reading Houellebecq is rather like viewing fascinating ruins; but instead of dilapidated buildings, one sees the decaying inner life of Western man.

Labrouste, unlike Binx Bolling in Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer (1961), can’t even be bothered with the search for meaning. And, in any case, he no longer has a reference point. “Nothing,” Labrouste says, “had given me the feeling that I had a place to live, or a context, let alone a reason.”

Louis Betty, writing in Without God: Michel Houellebecq and Materialist Horror (2017), by far the best English-language treatment of the author’s oeuvre, argues that Houellebecq’s readers, like his characters, find themselves “in profoundly postmodern country, with nothing to guide them except a vague notion of individual freedom that has degraded into a source of permanent anxiety.”

The meaninglessness of liquid living that dogs Labrouste is evident on a societal level; in France, Europe, and in the West. Rather than the flow of progress, Labrouste sees cultural exhaustion. “The third millennium,” he says, “had just begun, and for the West, which had previously been known as Judaeo-Christian, it was one millennium too many in the way that boxers have one fight too many.” In Houellebecq’s fiction, Betty argues, the “quest for man’s salvation in the absence of God is finished. All that remains is to resign oneself to suffering, death, and nothingness.” Or, for a little while, a diminutive white pill.

Labrouste’s parents chose suicide. He chooses delay. More pharmaceutical progress than generational improvement, it is as much hope as can be found in the novel. Failure, then, frames the story on an individual level as well. Florent-Claude Labrouste is a mid-level functionary in the agricultural bureaucracy of France. He has reached a plateau of sorts and, in taking leave of his work, takes stock of his life. Depressed and apathetic, he visits a psychiatrist (the profession makes him “want to spew”) and is prescribed an antidepressant. It allows him to have some kind of life and to narrate the novel in a flat and clinical way. It also kills his libido, which serves as a distorted measure of vitality in Houellebecq’s fiction.

Seeking respite from the loneliness of Paris and the lousiness of life, Labrouste travels to Manche in Normandy to visit his best friend “by default.” Aymeric is a dairy farmer caught between the old ways of milk production and the new global economy. He and his fellow milk producers are being crushed by the “secret invisible plan” of European Union bureaucrats who removed French milk quotas to allow for cheap imports. His farm is failing, his wife and children have left him, and options dwindle. Worse, he bears the weight of history.

In one poignant scene, Aymeric—the name is freighted with the glorious history of France and those kings and nobles who came before bearing some version of it, e.g. Aimery, Amalric—stares at a portrait of his ancestor Robert d’Harcourt, “the Strong.” Robert, a medieval knight with deep Norman roots, fought on Crusade with Richard the Lionheart. Along with the portrait, Labrouste observes his friend “at the weed again” and drinking vodka. The sense of generational diminution is inescapable. And it isn’t limited to the d’Harcourts of Normandy. The societal consequences of this hereditary thinning—as with France’s yellow vest protest movement, which Houellebecq anticipated—are shattering. Labrouste watches it all unravel, seeing in the general dissolution something of his own.

Labrouste knows agronomics but is ignorant of nature. He walks the many avenues of distraction, but no road to meaning. He enters the liminal only through the scope of a sniper rifle. Here is failure. His knowledge cannot save Aymeric; pleasurable distractions become impossible or undesirable; even the destructiveness of violence is out of reach. Of this acedia, Labrouste says of his generation, that they were “incapable of destroying, even less of rebuilding, anything.” And so the tale of Florent-Claude Labrouste isn’t a search but a summation. A summing up, he says, by the “banal words…apologising for the bother.”

Looking back on several failed relationships, Labrouste tries to assess what was lost. Not much really, and in the case of one ex-girlfriend it amounts to a gain, given the drunken denouement of her life. His fixation on Camille, a young woman with whom he once had what can only be called true intimacy, takes a disturbing turn and, what’s worse, gives rise to a horrifying plan to win her back.

But there is no going back for Labrouste. Or for Aymeric. Or for the West. So, with neither a whimper nor a bang, Labrouste reflects:

[N]ow there I was, a middle-aged Western man, sheltered from need for several years, with no relatives or friends, stripped of personal plans and of genuine interests, deeply disappointed by his previous professional life, whose emotional experiences had been variable but had the common feature of coming to an end, essentially deprived of reasons to live and of reasons to die.

It is no better for a godless West. “A civilization,” he observes, “just dies of weariness, of self-disgust—what could social democracy offer me? Nothing of course, just the perpetuation of absence, a call to oblivion.”

Houellebecq is not a Christian (he tends toward agnosticism), though he is, Betty argues, a profoundly religious writer. Still, he is no apologist for the faith. But neither is he a cheerleader for the progressive pieties that dominate French and European politics. For Houellebecq, the West—once supported and strengthened by Christianity—has become a formless entity. It is filled with the empty promises of atheistic materialism, liberalism, and globalism. The consequences are devastating. There may be no going back, but in all his novels he tries to imagine what it might look like going forward.

Serotonin is unmistakably Houellebecq. There are the usual—and crudely detailed—discussions of pornography and sex; the provocative observations of just about everyone (Belgians, Germans, Asians, pedophiles, radical ecologists, and, rather humorously, the Dutch); and ongoing social commentary. All of which have earned Houellebecq the title l’Enfant Terrible of French literature. Here, as in all his novels, he is both crude and profound, revolting and revelatory, often in the same paragraph. Sometimes in the same sentence. He is a literary mixed bag. But the reactions he inspires tend to the extreme. Most readers have either a visceral hatred or a gleeful—and slightly wicked—appreciation for him.

Houellebecq’s imaginative search for meaning, for a transcendent order that raises man beyond the material, has met with much criticism. He is alternately called a racist, misogynist, homophobe, xenophobe, Islamophobe, and misanthrope. He seems, in any case, to be an equal opportunity offender. But all of this is to miss the point. Indeed Houellebecq is one of the few novelists of our age who is really grappling with what remains of the West.

His loneliness in this endeavor isn’t encouraging. The pleasures he offers his readers may only be, for them as for Labrouste, a “small, white, scored oval tablet.”

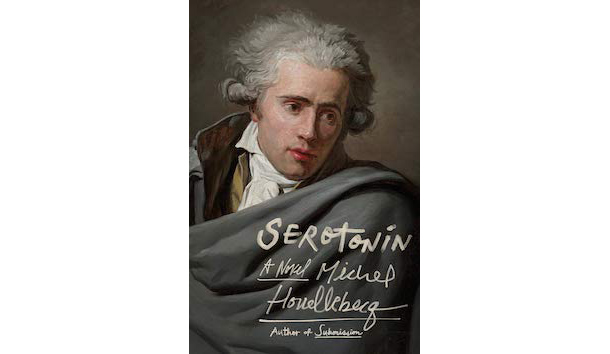

[Serotonin: A Novel by Michel Houellebecq, Translated by Shaun Whiteside (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) 320 pp., $27.00]

Leave a Reply