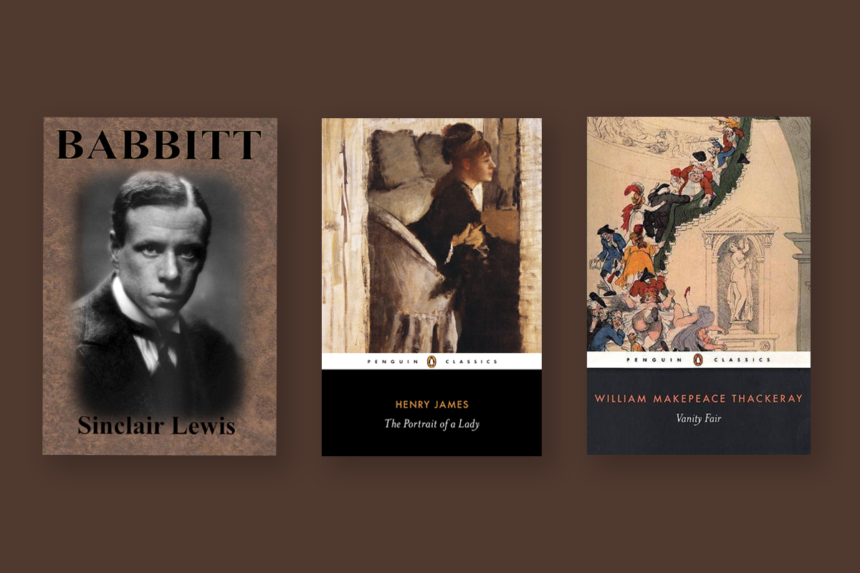

Although H. L. Mencken could discern “no plot whatever” in Sinclair Lewis’ Babbitt, he still praised the novel as “a social document of a high order.” The 1922 classic mordantly sketches a bygone America and the paladins who made it run. Even today, the title character’s surname still mocks guileless Americans who conform unthinkingly to middle-class standards.

George Babbitt sells real estate in Zenith, a fictional stand-in for the likes of Cincinnati or Omaha. He first extols Zenith as “the finest example of American life and prosperity to be found anywhere,” then grows disenchanted, and his subsequent midlife crisis provides ammunition for today’s elitists to sneer at Flyover America’s erstwhile local aristocracies.

It’s time to expunge the insult “Babbitt” from the dictionary, as it no longer describes any recognizable Americans. I imagine the Cancel Cabal is already working on it. Babbitt mocks blacks, Jews, Irish, Chinese, Italians, and probably a few others. Immune to the nascent “if it feels good do it” culture surrounding him, Babbitt priggishly scolds a close friend for cheating on his wife. Getting all puritanical, he dreads the corrosive effect infidelity has on the common good.

Babbitt’s stern warning—“If you haven’t got any moral consideration for yourself, you ought to have some for your position in the community”—contrasts sharply with the deceitful and tactless evasions Bill Clinton and Andrew Cuomo used to try to excuse their own affairs. Then again, unlike these two lascivious liberal icons, Babbitt’s mind wasn’t poisoned by a legal education or high office.

In polarized 2021 America, Babbitt sounds like a prophet. Speaking to the Zenith Real Estate Board, he ominously warns of “a lot of cowards who work undercover” including “irresponsible teachers and professors who constitute the worst of the gang.” Unlike university trustees who condone such academic mischief makers today, Babbitt reminds his fellow businessmen that they have “a duty to have those cusses fired.”

Those on the left and right both need to consider Babbitt’s deepest philosophical dilemma as they pursue their extremist utopias. Babbitt considered heaven “neither probable nor very interesting,” at least as his Presbyterian preacher portrayed it. Work and success no longer provided pleasure. Like the book’s title character, we too must ask ourselves what Lewis asks of Babbitt: “What was it all about? What did he want?”

—John Greenville

What do women want? This was Sigmund Freud’s great question, to which he could find no satisfactory answer—unless it was that women wanted to be men, which will hardly do in this day and age. This question has been a splendid one to explore for novelists, and two of the greatest examples are William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady.

Thackeray called his masterpiece, “a novel without a hero,” and his theme was that all of us, at one time or another, succumb to vanity, and that true nobility is all too rare, especially among the English aristocracy and middle class. James’s Portrait is less panoramic and satirical than Thackeray’s, although perhaps no less ironic. Isabel Archer, James’s heroine, unlike Becky Sharp, Thackeray’s equally attractive and insightful anti-heroine, does not have to claw her way to the top, leaving a husband, servants, friends, and a child injured or killed along the way, as did Thackeray’s charming and unscrupulous little minx. Because of her position at the pinnacle of American wealth and privilege, Isabel has easy entry into the European world of wonders that the impecunious orphan Becky fought to penetrate. But, because of puzzling contradictions in her own soul, Isabel manages to make a mess of her marriage, and chooses an alliance that will all but cripple her.

One finishes Vanity Fair with delight, dazzled by Thackeray’s sinuous, pyrotechnic prose and his essential humanity in describing woman’s inhumanity to man. James’s Olympian detachment is more unsettling. Even amidst war, poverty, and social dislocation, Thackeray’s characters often manage to have a rollicking good time; James’s characters, even in the midst of opulence, can’t seem easily to exist in their own skins. James was said to be a novelist who wrote like a psychologist, while his brother, famous Harvard psychologist William James, was said to write like a novelist.

If there is a single theme that unifies Thackeray’s and James’s wonderful and yet tonally different books, it is the destruction that ensues when a character adheres to nothing but her own whims, especially in the absence of the spiritual stability so hard to acquire in modernity.

Neither author conclusively solves the problem of female desire. Nevertheless, both of these works of art are helpful meditations on the always unsettling human condition. In our secular time, when the clueless dogma that gender is socially constructed is rising, Thackeray and James offer a necessary corrective.

—Stephen B. Presser

Leave a Reply