Not too long ago, the London Daily Telegraph resurrected a 1962 essay by Ian Fleming on “How to Write a Thriller,” in which the creator of James Bond said, “If you look back on the bestsellers you have read, you will find that they all have one quality: you simply have to turn the page.” Anthologist Kenneth Gregory’s collection of what he deems the best of the letters to the Times of London in this century, the fourth and final in a series of Cuckoo books, certainly fits the Fleming prescription. In turning page after page, the reader discovers that The Last Cuckoo is a marvelous chronicle of life’s ups and downs, its mysteries great and small, as described by the people who talk back to their newspapers through letters to the editor. Even the non-Anglophile can appreciate the humor in the May 2,1940, letter from a Mr. J.R.B. Branson, in which he discusses the joy of eating grass clippings, or in Mr. Gregory’s retort: “A typical meal chez Branson; lawn mowings mixed with lettuce leaves, sultanas, currants, rolled oats, sugar, and chopped rose-petals sprinkled over the whole. On 13 May Winston Churchill augmented Mr. Branson’s diet with the promise of ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat.'”

Newspaper editors have long suspected that what they give the reading public often fails to reflect the public’s tastes and interests, and thus they rely on correspondents to tell them what they miss. Well, at least until the creation of focus groups—where people off the street, for a free cup of coffee, evaluate what some polling expert thinks should be presented as news. Alas, the “Letters to the Editors” page has fallen victim to more trendy vehicles. (You ask why circulation nationwide is falling or remaining flat?) One suspects that even the mighty Times, now under the ownership of Rupert Murdoch, mirrors this trend, to judge from the letters showing up on its Internet edition. Yet for most of this century the Times was a powerful voice for journalistic democracy through its letters column, and it is this aspect of grassroots democracy (or grass-clippings democracy) that Mr. Gregory has captured so well in this anthology.

British eccentricity plays a big part in Mr. Gregory’s selections, especially the cuckoo-sighting letters from which the book takes its name. (In 1900, a correspondent claimed to have heard what he insisted was the first cuckoo of the year, not the last, thus settling the raging debate of when the 20th century began, 1900 or 1901. Look for the debate, cuckoo or not, in about two years.) Yet if readers of the Times were often eccentric, they were also practical, informative, and concerned with the search for truth. Even if they were not, many got a forum nonetheless, as did the Duce, who, in a letter dated June 26, 1925, defended his fascist experiment in Italy. (As Mr. Gregory notes, “There is no record of Hitler or Stalin writing to The Times.”) Speaking of Stalin and Hitler, Sir John Squire on January 11, 1936, commented not on the gathering storm across the channel but on his visit with a gentleman whose fox terrier named Wessex had a passion for listening to the wireless. A single line reveals the inspiration for the letter: “Melodiously forth came—well, I won’t say a Bach Fugue, for I do not remember asking Mr. Hardy whether his dog’s Bach was worse than his bite.”

Many of the letters chronicle Britain’s perceived decline, still thought to be terminal when The Last Cuckoo was first published in England in 1987. As a John Cope asked on April 28, 1982, “In one single week’s news items I have heard the following names preceded by the title ‘Mister,’ and in one case ‘Sir’: Andy, Ben, Bert, Bill, Bob, Dick, Ed, Fred, Freddie Geoff, Jack, Jim, Ken, Max, Mike, Pat, Ray, Rob, Ron, Sam, Sid, Stan, Steve, Terry, Tiny Tom, Tony, Vic, Viv and Will. Are we to understand that at their baptisms not one of these people was given a real Christian name?” Mr. Gregory deadpans in response: “On 12 October 1963 The Times published a letter from ‘Anthony Wedgwood Benn’; a decade later, the same MP was Tony Benn.'”

Many of the correspondents selected for The Last Cuckoo are names familiar throughout the world: Winston Churchill, Arthur Conan Doyle, Rebecca West, Agatha Christie, Evelyn Waugh, and George Bernard Shaw. Few of the greats met the test, as explained by correspondent Sylvia Margolis on January 28, 1970, for epistolary publication—”I can bear witness that the prime qualification you need to get letters published in The Times is eccentricity”—in quite the way Neville Chamberlain did in his letter of January 24, 1933, in which he reported the sighting of a grey wagtail in St. James’s Park. As Mr. Gregory noted: “On 30 January Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.” (He could have added that Neville Chamberlain was to go down in history more for what he did not see than for what he did.)

Like any good page-turner, The Last Cuckoo does not need much interpretation from its editor: the characters do the heavy lifting here. In the end readers may well find themselves asking, Why aren’t letters to American newspapers in the same league with these? Good question, but not one of any interest to focus groups right now.

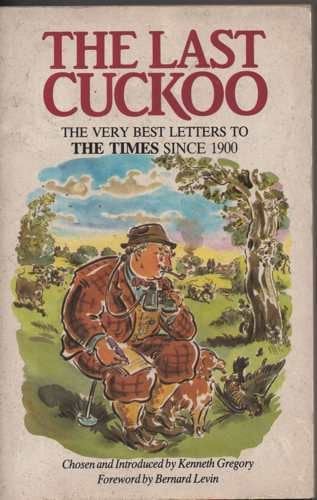

[The Last Cuckoo: The Very Best Letters to The Times since 1900, edited by Kenneth Gregory (Pleasantvilk, NY: The Akadine Press) 343 pages, $15.95]

Leave a Reply