“Folly is often more cruel in the consequences than malice can be in the intent.”

—Halifax

The correspondence of Edmund Burke, whose letters help to illuminate his published works, was not available in a complete edition until 1978. Today, however, it seems that every aspiring journalist begins saving his correspondence even before his first word-processed piece is published. If current trends continue, we can look forward in the near future to definitive editions of the correspondence of Francis Fukuyama and Bill Bennett (ghostwritten, in the latter case).

John Lukacs has remarked that inflation characterizes modern life, and the explosion of published works of correspondence is just one sign of that inflation. Of course, inflated money is still worth something, and some of these volumes are actually worth reading. The recent collection of the correspondence between Lukacs and George Kennan, George F. Kennan and the Origins of Containment, 1944-1946, is indispensable for those who wish to rise above ideological categories and to place the Cold War in its proper historical context. The correspondence between two Ingersoll Prize winners, Shelby Foote and Walker Percy, is of similar interest to students of Southern history. Not all works of this type, however, are worth sacrificing the lives of trees. At an American Political Science Association annual convention a few years back, I attended a session devoted to the (then) newly published correspondence between Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin. The highlight of the panel was a paper by a Straussian Voegelinian (or perhaps he was a Voegelinian Straussian) expounding the esoteric meaning of Strauss’s apologies, in his letters to Voegelin, for writing on scrap paper.

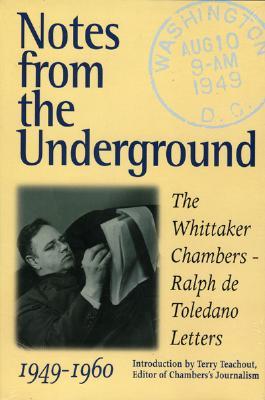

Happily, Notes from the Underground is one of the more interesting works of this genre, even though there are no major revelations about the Alger Hiss trial. In fact, most of Chambers’ comments on political events will surprise no one who has read William F. Buckley’s Odyssey of a Friend (another volume of Chambers’ correspondence), Allan Weinstein’s Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case, or Sam Tanenhaus’s Whittaker Chambers: A Biography. But these letters, exchanged between two close friends on the anticommunist right, constitute a valuable period piece that gives depth and texture to an era that most people today view only through the distorting ideological lens of the Reagan years.

That era saw a different politician rise to national prominence on the strength of his anticommunist credentials. Whittaker Chambers and Ralph de Toledano began their correspondence in 1949, while Toledano was covering the first trial of/Alger Hiss for Newsweek. Some of their earliest letters discuss Richard Nixon’s speech on the floor of the House of Representatives following Hiss’s perjury conviction, a speech which, in Toledano’s words, “shook Congress and placed him in the center of the national political stage.” Their last letters were exchanged a few days before Nixon was defeated by John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election and temporarily departed center stage. Along the way, their correspondence paints a picture of Nixon that is more subtle and complex than standard conservative interpretations. While acknowledging Nixon’s political strength and his early devotion to the anticommunist cause, both Chambers and Toledano begin to doubt Nixon’s devotion to his friends, a character flaw that ultimately would lead to Watergate, In May 1959, Chambers, discussing Nixon, wrote to Toledano:

The world is rather sensibly ordered . . . among lions and mice. . . . But . . . I question the wisdom of . . . the Lion who seems not to grasp the workings of that order. . . . Or who forgets what mice meant to him in the inglorious days, and may mean again. . . . I think the Lion has forgotten that even summer days are interspersed with, and sometimes terminated by, the night of the hunter. Then the Lion may roar: “‘Mouse! Mouse!” but finds he is lord only of the closing jungle, or a veldt whose false peace dissembles the nets no mouse will gnaw him free of, while the treacherous forms circle softly in.

Chambers exhibits a similar ambivalence about Senator Joseph McCarthy. In a gloss on one of his own letters from 1951, Toledano writes that Chambers told him privately that “Joe is sometimes a rascal, but he’s our rascal.” In a letter from 1954, Chambers discussed the tactics of anticommunists. While clearly unhappy with those who seemed not to put up much of a fight, Chambers was also concerned about others whose tactics could be self-destructive:

Why is it that every time I move in at the risk of my skin and drop a grenade through the slit in the pillbox, our side rushes off into the bushes . . . while the others, who at least know what a grenade is when they receive one, swarm out shooting? The answer is: our side does not know the nature of the enemy, therefore, the nature of the war he enjoins, therefore, the nature of the tactics. So the simple tactic of exploiting an opening is inconceivable to them. . . . Senator McCarthy’s notion of tactics is to break the rules, saturate the enemy with poison gas, and then charge through the contaminated area, shouting Comanche war cries.

The supposed triumph of “conservatism” that culminated in Ronald Reagan’s eight-year reign did much to obscure the political and intellectual history of the American right in this century. Those who find it surprising that Chambers may have disagreed with Nixon and McCarthy on questions of friendship and tactics will be even more disturbed to read Chambers’ comments on Hannah Arendt and Ludwig von Mises, two other heroes in the conservative pantheon. “Miss or Mrs. Arendt,” Chambers wrote in 1953, “appears to be one of those Central European women who has read too much and has nothing to sustain it except an intensity which shakes her like an electric motor that is about to shake loose from its base.” Responding to Chambers’ perceptive assessment of Arendt, Toledano nonetheless pointed out that Arendt did have a base: “Mrs. Arendt is married to a man whose ex-ness is in a very dubious state. As a result, in attacking ex-Communists, she is protecting a vested interest.”

While Chambers did not question Ludwig von Mises’ ability as an economic theoretician, he roundly criticized Mises’ The Anti-Capitalist Mentality:

I should consider it one of the most pernicious pieces of writing that the Right has produced. . . . By pernicious I mean the effect that follows when a mind, which speaks with authority in a special field (economics), uses that authority (but not the field it is based in), to offer a false study of our dilemma. The result of this (insofar as its silliness is not self-evident) must be to mislead thousands about the nature of that dilemma. . . . This grossly shallow man has left the field of economics for the field of mass psychology. He has proclaimed, rather than deduced, that the anticapitalist mood of our time is the result of “envy and ignorance.” . . . Marx himself pointed out that poverty is never aware of its condition until wealth builds a house next door. In this sense, von Mises’s capitalists are all Marxists; they have erected the unsettling contrast into the operating principle of the mass market.

Whether we agree or disagree with Chambers, his arguments with Arendt and Mises were not merely over tactics; they followed from first principles. And yet, like the Greeks who incorporated into their pantheon the gods of the peoples they conquered, or the Straussians who proclaim anyone that they admire a “philosopher” (and anyone they dislike, a “believer”), conservatives over the past 20 years or so have held up mutually contradictory figures for emulation. (I’m certain it would not take very long to find an article in a back issue of, say, National Review, praising Chambers, Arendt, and Mises, without the faintest hint of irony or the slightest suggestion that the three represented radically different views.) For an intellectual (and even a political) movement to survive, it is as important to exclude certain figures as it is to include others. When the pantheon becomes too large, intellectual incoherence and political impotence are the likely results.

Lacking an historical sense, the American right has floundered. If it is to evolve into a serious intellectual and political movement, its leaders must reexamine their pantheon. But to do so, they will have to relive the debates over first principles that the “one big happy family” conservatism of the Reagan years sought so desperately to avoid, and that the current neoconservative hegemony forbids. Notes from the Underground reminds us that the American right once took first principles seriously. For that reminder, we should thank Ralph de Toledano for this book.

[Notes from the Underground: The Whittaker Chambers-Ralph de Toledano Letters, edited and annotated by Ralph de Toledano (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc.) 342 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply