A new kind of animal stalks the land these days. If you listen closely, you can hear its strange call: chest-thumping roars alternating with keening wails and abundant sniffles. And if you look carefully, you’ll doubtless soon spot one, for they clone faster than jackrabbits. This new critter is now all around us, and the poet Robert Bly has provided a field manual to aid in its identification.

The animal in question is the New American Male (1990’s), a dusted-off Gary Cooperesque stalwart (1950’s) who’s not afraid to cry in public (1970’s), a thirty-something hybrid (1980’s) who combines the sensibilities of Alan Alda, John Wayne, and Pee-Wee Herman. He travels in packs. He can often be found in woodland retreats, pounding on tom-toms (1960’s) and weeping over his failure to connect with his taciturn father. Our shellshocked Boy Scout likes to call himself a “wild man,” to doff his cordovan wingtips and grey suit of a weekend and roam the dark forests, barefoot, T-shirted.

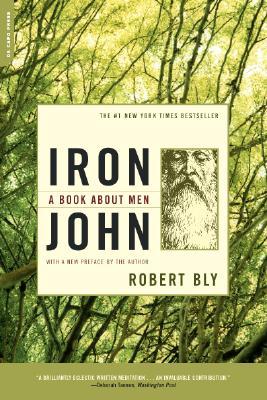

Robert Bly, a poet and translator of great distinction, has at the age of 65 discovered that he, too, is a wild man. In Iron John—its tide is taken from a European rite-of-passage folktale that can be found in the pages of the Brothers Grimm and, in far too many permutations, in the book under review—Bly laments the rise of the modern pasty, malleable, “soft man,” pounded into shape by the commissars of modern feminism, still inclined to use phrases like “let me share your space” and “I can relate to that.” These men, Bly observes,

are not happy. You quickly notice the lack of energy in them. They are life-preserving but not exactly life-giving. Ironically, you often see these men with strong women who positively radiate energy.

No more namby-pambyism, Bly urges; no more unseemly displays of deference and accommodation to these iron maidens. In his cri de coeur, he instead demands that all real men find their “interior warriors” and make themselves fit to take up long-rusty Excaliburs and sally forth into battle.

Inside every man, it seems, there’s a King Arthur screaming to get out. Bly aims to spring him through a series of pop-myth recipes for success, complete with archetypal kings and queens, dragons, naiads and dryads, caverns, and sweat lodges. (To read Ely’s pages, you’d think Joseph Campbell had returned from the dead for one last fling with the gods.) But, Bly urges, let us not allow our Arthur to degenerate into some modern Conan. We’ll do the ordering at dinner, thank you, but on occasion we’ll also let our dates select the topic of conversation.

The befuddled are everywhere legion, evidenced by the overflowing shelves devoted to self-help panaceas and New Age mysticism, to cures for every psychic ailment real and imagined, to every social risk. Iron John is meant for these survivors of the I’m-okay-you’re-okay generation, but it is nowhere near as obnoxious as the run of the literature, and Robert Bly does have his points. Few thoughtful people, after all, would argue that these are happy days, and there are far too many men—and women—out in the heartless world who lack any emotional anchorage whatever; we would surely all do well to learn how to grapple with our emotions more effectively. If becoming “wild” and taking up the sword of the samurai within us yields a bit more joy in men’s lives, if it contributes to some truce in the war between the sexes, then, as silly as Iron John seems, Robert Bly’s earnest essay will have done its job.

But I suspect that it will not, and that the New American Male will soon be driven into extinction, to be stored in history’s attic next to platform shoes and mood rings. The interested reader would do better to skip Iron John and instead invest in a copy of Muddy Waters’ blues stomper “Mannish Boy,” a T-shirt, and a six-pack. Suitably armed, he can then head to the woods to commune with his inner nature—if, that is, he can find a moment’s solace among the hordes of this brooding new beast.

[Iron John, by Robert Bly (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley) 268 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply