Every night before bed, Eleanor Roosevelt—first lady, feminist, and the spirit Hillary Clinton most wants to contact in the Great Beyond—knelt beside her bed and prayed her improvised prayer:

Our Father, who has set a restlessness in our hearts and made us all seekers after that which we can never fully find, forbid us to be satisfied with what we make of life. Draw us from base content and set our eyes on far-off goals . . .

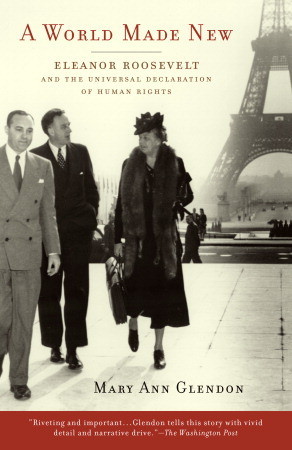

It continues, but that excerpt should be enough for you to get the idea. Franklin Roosevelt, less of a theologian, was rumored to have prayed “Dear God, please make Eleanor tired,” according to Mary Ann Glendon, Harvard law professor, in this attempt at vindicating of Mrs. Roosevelt and her grand achievement, the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. A less sympathetic biographer might have included the popular, more pointed dismissal: “If he could stand up, he’d knock her down.”

The genesis of this book, Glendon writes, was the misinterpretation, misunderstanding, misuse, and abuse that she thinks the declaration has fallen prey to since it was approved, with no dissenting votes, by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. Multiculturalists and the parties of resentment from Third World countries charge that it represents the unjustified imposition of Western morality. Realpolitikers doubt the efficacy of a nonbinding declaration of principles. Libertarians and classical liberals shudder at its conflation of positive and negative rights. Theists blanch at its intentional lack of reference to a creator. All, the Harvard professor believes, are sorely mistaken (more or less).

The first and loudest charge—that the document amounts to an imposition of Western thought and morality—is the one Glendon takes the greatest pains to refute. With regard to the question of whether “rights” can actually be considered universal, she notes that a subcommittee of the United Nations invited comment from representatives of all of the world’s great religious traditions and cultures. Glendon finds their responses, which she thinks suggest that most cultures share many of the same beliefs with regard to civil rights (even if they had remained unexpressed in the terms of the fairly recent advent of “rights language”), to be “encouraging.”

Certain cultures or nations were not, she claims, purposely shut out of the discussion. The people who shaped the declaration included Greek Orthodox Arab Lebonese philosophy professor Charles Malik; René Cassin, Frenchman and secular Jew; Peng-chun Chang, playwright and representative of noncommunist Confucionist China; Alexei Pavlov, nephew of Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, of the Soviet Union; Hansa Mehta of Hindu India; and Eleanor Roosevelt herself, liberal, universalist, woman of causes. Further, the declaration was vigorously debated and then approved—or allowed to pass unobstructed—by representatives of European, Latin American, African, Muslim, Asian, and North American nations.

In the end, Glendon throws up her rhetorical hands and wonders aloud what in the world the multicultis could be talking about:

To accept the claim that meaningful cross-cultural discussions of freedom and dignity are impossible is to give up on the hope that the political fate of humanity can be affected by reason and choice.

It also, she further charges, gives the last word to the Athenians as they were about to invade the peaceful island of Melos. Their response to the diplomats from Melos still resonates: “You know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

This is wonderfully crafted—perhaps even nominally persuasive—rhetoric, but I have to wonder if the back story of A World Made New bears out Glendon’s contention that the declaration speaks up for the meaningful rights of all. The arguments were set in the context of an emerging Cold War between America and the Soviet Union, roughly “equals in power” at the time. While other countries and cultures made substantial contribution to the conference, it is highly unlikely that the declaration would have had any force—in terms of practical politics—if either giant had walked out. Thus, the United States or the Soviet Union could have effectively scuttled the whole process at will. No extra points will be awarded to those who determine which side exploited this arrangement more often.

At several points in the drafting of the declaration, the Soviet Union success-fully pushed to water down or muddle the document in order to accommodate its own despotism or to come up with rhetorical trump cards to play against America. Language referring to a “creator” and even “nature” was stricken from the preamble as being insufficiently secular and, therefore, incompletely universal. The word “private” was removed from the property clause to avoid offending countries with total state ownership of the means of production. Any mention of a people’s right to overthrow its despotic regime was left out. The United States became the only country to vote against a provision that would tie salaries to family size. And Soviet representatives and their puppet states proved so contentious that even a soul as accommodating as Mrs. Roosevelt at one point found it necessary to speak out:

I think the time has come for some very straight thinking among us all. The ultimate objective that we have is to create better understanding among us all, and I will acknowledge this is going to be difficult. And I will give you the reason why. I have never heard a representative of any of the USSR bloc acknowledge that in any way their government can be wrong.

One argument Glendon does not take seriously is that the compromises necessary to give birth to the declaration ended up hatching something closer in theory to “liberty, equality, and fraternity” than “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In the book’s most maddening undeveloped aside, she writes

Iraq’s A. Abadi argued, as philosopher Robert Nozick would years later, that it is logically impossible for human beings to be both free and equal since inequality is the inevitable result when people are free to develop all their latent talents.

Yes? And? The text cries out for explanation.

And yet, as Mrs. Roosevelt’s words demonstrate, though the declaration is full of compromises and muddled thinking and its official guardian, the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, recently replaced the United States with such morally pristine nations as the Sudan, there may have been some value in it. The Soviets were too embarrassed, finally, to obstruct a document that extolled such basic freedoms as untrammeled speech and movement. They sat there silent and stone-faced as civilized nations affirmed these as basic decencies below which only barbarians would sink, and were shamed by it. Further, the declaration proved to be a bludgeon America would employ successfully to exact many excuses and not a few concessions from the barbarians.

Though that is a victory of sorts, it represents a strategic one “between equals in power” and not the sort of which I suspect Professor Glendon would approve.

[A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, by Mary Ann Glendon (New York: Random House) 333 pp., $25.95]

Leave a Reply