Charles Portis’s fifth novel is of course a pleasure in its own right, but it’s also an occasion—or should I say I am making it one—for reflecting on its author and his work, his style, his literary profile, the way he does things with words. I’d like to do that, because I don’t think, in spite of his success, that Mr. Portis has entirely gotten his due, the recognition that he deserves as a writer.

As he shows once again in Gringos, Charles Portis is a deceptively laid-back performer. His narrator, Jimmy Burns, is so relaxed that we forget just how much is going on beneath the surface of his pages as we scan them. The ride is so absorbing for its incidental joys that we forget where we are going. We don’t care. Later we realize that the journey was more thoughtfully conducted than we ever knew. The nonchalance of the experience reflects the sprezzatura of the artist.

I suppose that Charles Portis’s style and diction are not only personal accomplishments but are products of his Arkansas background. He seems to have advanced the tradition of southwestern or frontier humor as we have received it from Thorpe and Twain and Faulkner, and to have forged his own unique sound and subject matter. That tone of his, in Norwood, The Dog of the South, and Gringos, is a special blend compounded of cunning and naiveté, of rustic whimsy and contemporary cool, of first-person narrative and neurotic digression. There’s an arbitrary, quirky readiness to leave the line of the tale, to pursue any point, to fuzz the focus, that is reminiscent of Eudora Welty’s speaker in “Why I Live at the P.O.” Portis’s narrators are so often beset by con men, madmen, and cranks that their own hobbyhorses can sometimes confuse our perspective. Yet their stories have the compelling force of that of the Ancient Mariner.

Gringos is about Americans in Mexico, where no amount of craziness can erase our sense of the presence of the past. Portis catches with effortless accuracy the surreal world that juxtaposes a garbage dump here with a pre-Colombian temple there. The overlay of Hispanic culture reminds me that the picaresque, on-the-road quality of Portis’s novels is beautifully affirmed in Gringos, some of whose characters remind me of Don Quixote, and one or two of Sancho Panza.

The overwhelming background of Mexico—the Catholic, the pagan, the Spanish, and the Indian cultures—assert themselves even as various Gringos and locals attempt to exploit them or trash them or steal them or subvert them, or even penetrate their mysteries. Jimmy Burns, a lost soul who hauls junk and locates missing persons, sets out to find one and winds up saving another—not for money. There’s a hint at a kind of grace, a marriage, a new dispensation, one embedded in a tale of idols and dwarfs and witches and ritual sacrifices, as well as little men from flying saucers who must exist (mustn’t they?) to explain all those Mayan ruins.

It is Refugio, the Sancho character, who declares, “You never know what the day will bring,” which may be true outside Mexico and outside a novel by Charles Portis, but is certainly the rule within those entities. Let’s say that the fictional Mexico is a Portisland, and leave it at that. Ironies abound. “Things had turned around, and now it was the palefaces who were being taken in with beads and trinkets.” “You never know what you’ll run into in Mexico, John Knox in a guayabera shirt, or a rain of tadpoles in the desert, or a strangely empty plaza in the heart of a teeming city with not even a bird to be seen.” Portisland, if not Mexico, is a place where anything can happen, and does.

But in a novel by Charles Portis, what happens next sneaks up on the reader, who is so busy listening to what the narrator says that he neglects to watch out for big surprises. When one woman challenges Jimmy Burns with, ” ‘You’re afraid of smart women, aren’t you?'” his internal comment steals the show:

She had used this ploy before, having heard via the female bush telegraph that it was unanswerable. She was right though. I was leery of them. Art and Mike said taking an intellectual woman into your home was like taking in a baby raccoon. They were both amusing for awhile but soon became randomly vicious and learned how to open the refrigerator.

By an idiosyncratic art of combination, Portis has honed a style so beguiling that his books are consumed for the sheer pleasure of their discourse, rather than for the resolution of suspense. The man has style.

So Jimmy Burns speaks in a knowing, rueful, and flexible way that we have heard before and would know anywhere. He seems to be superficial but is shrewd; he seems to be anti-intellectual, but reveals knowledge of history and evidence of thoughtfulness. His good humor and openness are appealing, but they have their limits. I like what he says about UFO literature: “Still, the flying saucer books were fun to read and there weren’t nearly enough of them to suit me. I liked the belligerent ones best, that took no crap off the science establishment.” I relished also his description of Mott, a minor gringo:

Mott always looked sprightly and pleased with himself, like Harry Truman at the piano, with his rimless glasses and neatly combed hair. He had gone crazy in the army and now received a check each month, having been declared fifty percent psychologically disabled. Had they determined him to be half crazy all the time or full crazy half the time? Mott said the VA doctors never would spell it out for him. He had whatever the opposite of paranoia is called. He thought everybody liked him and took a deep personal interest in his welfare. But then everybody did like him.

Stuff like that, of course, cannot always distract us from the progression of plot, or from learning why “‘The password tonight is L.C. Smith.'” The bumpy ride of Gringos proves that Charles Portis has still got what it takes, and that down-home thoughts about food suggest something too about the enjoyment of novels: “Mashed potatoes are the better for a few lumps, in my opinion, and gravy too for that matter.”

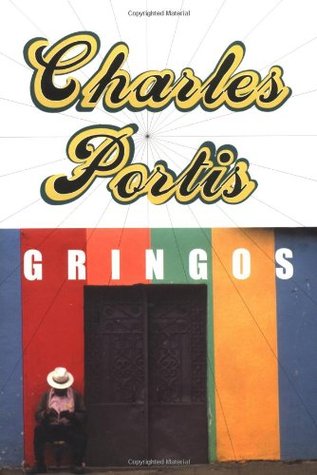

[Gringos, by Charles Portis (New York: Simon & Schuster) 269 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply