Few American objects attract more scorn than the federal Internal Revenue Code. When initially drafted in 1914, it contained 11,400 words, about the length of a long magazine article. Today, the Code weighs in at about four million words, with another six million in supportive regulations. Its garbled syntax is easily ridiculed. Tax attorney Joseph B. Darby III—called the “Mark Twain of tax writers”—cites a one-sentence passage on “collapsible corporations” that contains 342 words (more than the Gettysburg Address), 25 parentheses, 17 commas, two dashes, and a lone period.

Of course, politicians—particularly those on the right—routinely rail against the Code for its complexity. Back in 1986, President Ronald Reagan denounced the document as a “haven for special interests and tax manipulators, but an impossible frustration for everybody else.” Thirty years later, House Speaker Paul Ryan’s Tax Reform Task Force reports that “it again has become a complicated mess of multiple brackets, high rates, and special-interest provisions.” Americans must devote “their hard-earned dollars and their hard-pressed time to complying with an overly complicated and complex code.” Once again, the Code must be simplified!

This cry is exactly wrong. In fact, both libertarians and traditionalist conservatives should defend the Internal Revenue Code, pretty much as it stands, albeit for different reasons.

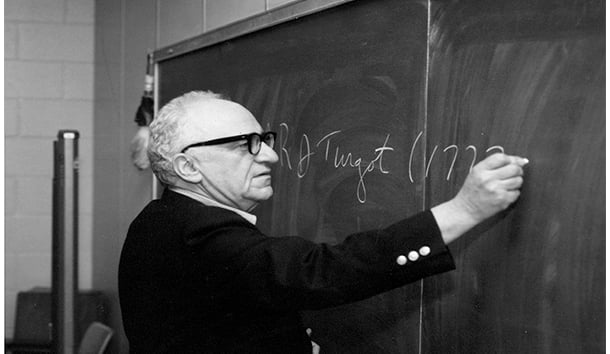

I learned the libertarian argument for this position from the late Murray Rothbard. During the Paleoconservative Versus Neoconservative War of 1989-91, this renegade economist rallied to the Paleo Cause. We began a modest correspondence and met a number of times—commonly over a beer. I was repeatedly surprised by the intellectual curiosity and the unpredictability of this reputed anarcho-libertarian ideologue. Specifically, we discovered to our mutual delight that—in independent breaks with the official right—we both had opposed the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and the simplifying “flat tax” philosophy behind it. As he wrote to me, the effort to “close the [tax] loopholes” and to distribute the tax burden “fairly” were “egalitarian and Jacobinical.”

Rothbard continued:

[S]uch people . . . would regard your proposal of a [new] tax credit per child . . . as illegitimate “social engineering.” In my view, however, it is neither illegitimate nor social engineering to allow people to keep more of their hard earned money; so, bravo for your proposal!

He and I subsequently agreed that “tax loopholes” were better labeled “zones of liberty,” places where families might shelter their money and property from a grasping state apparatus and its politician acolytes.

Implicit in Murray Rothbard’s argument was the assumption that the more complicated the tax code became, the better. In a January 2016 campaign speech, Donald Trump actually seemed to catch this spirit. Defending the small amount of income tax paid by his family businesses, he explained, “I mean, I pay as little as possible. I use every single thing in the book.” Exactly!

Traditionalist conservatives should also oppose the Jacobin cry for “Simplification!” It is helpful here to recall the era of the Founding Fathers. A widely read Student’s Law-Dictionary, published in London in 1740, was careful to distinguish between the concept of liberty in a general sense, and liberty in a legal sense: “Liberty, in a legal Sense, denotes some Privilege that is held by Charter or Prescription . . . ” Other definitions of liberty from the 18th century include “a Privilege by which Men enjoy some Benefit or Favour beyond the ordinary Subject” (John Kersey, 1708), and “Franchises and Privileges which the Subjects have of the Gift of the King” (Edward and Charles Dilly, British Liberties, 1766).

As political theorist Barry Shain notes in his fine book The Myth of American Individualism, this understanding of liberty was necessarily in the plural. “Liberties” were historically grounded corporate privileges and rights. This definition took shape in the medieval era, and was expressed in the Magna Carta. As historian Alan Pollard has put it, this famed document “was a charter not of liberty but of liberties.” In 1776, this understanding of liberties was still intact.

Importantly, these “liberties” were in different ways enjoyed by all. Evolving slowly over time, every town or little village, every trade or professional guild, every monastic or commercial corporation, and every station in life (lord, serf, merchant, seaman, artisan) had claim to one or more—usually many more—of these liberties. Exemptions from a tax or forced labor on the King’s Highway, a right to collect acorns in the royal forest, an immunity from prosecution for acts otherwise illegal: Such examples reveal a rich, organic tapestry that recognized and protected the true diversity in human relationships and communities.

These liberties, moreover, were the political and legal manifestations of the “little platoons” of life that traditionalist conservative Edmund Burke so zealously defended. Writing in 1790, he referred to the British constitution, which preserves “a unity in so great a diversity of its parts.” Alongside the Crown, an inheritable peerage, and the House of Commons were “a people inheriting privileges, franchises, and liberties, from a long line of ancestors.” Such a commonwealth was rooted in history and custom, “the happy effect of following nature, which is wisdom without reflection.”

The enemy of such a constitution and its liberties was the “spirit of innovation,” derived from “a selfish temper and confined views.” This was the heart of Burke’s opposition to the French Revolution of 1789. Across the Channel, he saw the Jacobins appeal to Reason and Simplicity in order to assault and destroy the parallel liberties of the French people. Town charters, corporate privileges, ancient rights and exemptions: All were being swept away as unfair and inefficient, to be replaced by a new order dictated solely by rational calculation. The Jacobins were “destroying at their pleasure the whole original fabric of their society,” breaking “the whole chain and continuity of the commonwealth.” In place of a practical government made for the happiness of its people was one pursuing “a spectacle of uniformity to gratify the schemes of visionary politicians.”

The current Internal Revenue Code should be seen as the American charter of liberties, a collection of exemptions, privileges, and special protections that has grown organically for over a century. When it is charged with being complex, irrational, or medieval, the common conservative response should be, “Yes! Those are its strengths, not its weaknesses.” When it is charged with being unfair and inefficient, the answer again should be, “Yes! This is the price incurred for authentic liberty.”

In a curious way, the complexity of the Code simply reflects the wonderful diversity of American life. Consider the following seven passages from the IRC, dealing with “Gross Income—Exclusions” and related matters.

First: “Gross income shall not include amounts received by a foster care provider during the taxable year” (12-131).

Second: Tax on income from certain properties “shall be suspended during any period that such individual or such individual’s spouse is serving on qualified official extended duty . . . as an employee of the intelligence community . . . [including] the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency,” etc. (12-121).

Third: “The taxpayer shall be entitled to an additional amount of $600 . . . for himself if he is blind at the close of the business year” (26-63).

Fourth: Certain payments to a “terminally ill individual” are excluded from tax, defined as “an individual who has been certified by a physician as having an illness or physical condition which can reasonably be expected to result in death in 24 months or less” (26-101).

Fifth: “Amounts received in respect of the services of a child shall be included in [the child’s] gross income and not in the gross income of the parent, even though such amounts are not received by the child” (26-73).

Sixth: “Gross income does not include compensation received for active service as a member of the Armed Forces of the United States for any month during any part of which such member is in a missing status . . . [as a result of] the Vietnam War” (26-112).

And seventh: “There shall be allowed as a deduction . . . [l]osses from wagering transactions only to the extent of the gains from such transactions” (26-165).

These are liberties held precious by foster parents, spies, the blind, the dying, greedy parents, very long-term POWs, and gamblers. Such provisions in the Code can be multiplied many thousands of times. All are woven into the fabric of our national life. And yet, the Simplifiers would destroy them, utterly and completely.

Admittedly, such tax privileges do fall, in some instances, unevenly. A few years ago, for example, General Electric was widely faulted for rolling up $5.1 billion in U.S. profits, while paying negligible federal income tax. Many “liberties,” no doubt, contributed to this. Nonetheless, even the lowliest, poorest, and most pathetic homeless persons in this land benefit from the U.S. tax code: Tax-deductible contributions provide them hot food in church kitchens, and clothing and shelter from similar sources. These are their “liberties” (once removed), also threatened by the new and extreme Simplifiers who would toss out the charitable deduction along with all the others.

Would Edmund Burke love the contemporary U.S. Internal Revenue Code? That might be going too far. However, I do believe that he would understand and appreciate it.

And so, I urge all conservatives—be they Rothbard-style libertarians or Burkean traditionalists—to stop the Simplifiers and protect the tax code from their revolutionary scheme—for the sake of liberty . . . and liberties!

Leave a Reply