This past semester a group of bored yet curious students at my university invited faculty to participate in a lunch-hour debate. When the organizers first contacted me they referenced several of my former students who praised my heretical outspokenness as key to my selection. They hoped I might provoke their classmates into actions more meaningful than dreaming about their cubicle-bound summer internships or feathering their LinkedIn pages. The invitation sparked two thoughts—one naive, and the other realistic. The Pollyanna in me hoped that my undergraduate references had finally tired of pabulum-spewing instructors hedging their every utterance to ward off the p.c. vigilantes’ unforgiving wrath. Or, more likely, a cabal of tuition-paying radicals was setting me up.

Ever at the ready with their nooses and pitchforks in the form of iPhones and laptops, millennial social justice warriors offer no concessions in their barbaric war against any utterance even tangentially in support of the good, the true, and the beautiful. I on the other hand, always on the lookout for a good argument while leery of my impending suicidal defenestration, agreed to take part under one condition: I get to propose the resolution up for debate. One week before the event the other faculty participant and I met with two student coordinators to discuss a range of possible topics. Like every other bubble-enclosed American college campus, mine still reeled from Donald Trump’s tumultuous campaign and bombshell victory. Despite six months of fitful convalescence occupied with casuistic teach-ins, puerile walkouts, and mandatory “NOT my President” buttons, students and faculty at my school could still not bear the mere mention of the 45th president’s name.

So in order to provide a teaching moment I suggested we discuss a campaign topic that shook both students and faculty nationwide to the core last November. With no objections from the debate organizers or faculty participants, we agreed to the resolution “American corporations have a duty to American workers,” with me defending the affirmative. Such patently obvious statements require justification only on 21st century American college campuses. Voters in the Rust Belt agreed with this simple statement despite Candidate Clinton’s consignment of them to the “basket of deplorables” for doing so. Nowadays, concepts like “American” and “duty” only come in for disparagement in a university setting.

When debate day finally arrived I noticed the friendly faces of several former and current students in the crowd. I sat on the dais with my fellow faculty members wondering just how objectionable they had found my proposed resolution. I didn’t have to wait long. As the moderator read the resolution to the crowd, the glowering colleague closest to me leaned over and hissed, “You don’t really believe that, do you?” In my seminars I must constantly encourage my cowed students to voice arguments that don’t necessarily reflect their personal beliefs. Good seminars depend on diverse viewpoints. Sadly, that message needs to be redoubled in today’s faculty context.

Nonetheless, I started my defense of American corporations’ duty to American workers by reminding the audience that the volunteer firefighters who respond to emergencies at those same corporations’ facilities do so out of a sense of duty. Likewise, I added, American soldiers defend American corporate interests around the globe not for their paltry pay, but more so from a sense of duty to their fellow Americans, as well as to their nation and its institutions. I pointed out that American taxpayers also fund the infrastructural, legal, and regulatory apparatuses that foster a fertile environment for American corporate prosperity. And I pled for American corporations to reciprocate, to show the same respect due their workers, grounded in the obligations that all citizens have to their compatriots. I ended by saying that one could substitute British, French, or German corporations and British, French, or German workers for the American corporations and American workers in the resolution with no change to the overall conclusion. This reciprocal duty, I reminded the crowd, transcends national borders.

Needless to say, my hallucinatory interlocutor imagined she heard me quoting from Charles Lindbergh’s 1941 Des Moines speech when I wasn’t shouting “America First!” I couldn’t even picture her revulsion at my obvious disdain for “global citizenship.” And what if she were to learn I own just one passport, and an American one at that? The audience’s positive reaction to my heterodox argument should have emboldened me to go in for the kill. I toyed with the idea of citing a political activist whose escapades in 1996 clearly marked him, in retrospect, as a far right wing, xenophobic, proto-Trumper.

The late-90’s reactionary I’m referring to wrote to the CEOs of dozens of large American corporations with a simple request. But first he reminded them how their companies had benefited from being located in the United States, “the country that bred them, built them, subsidized them and defended them.” He then made his outrageous appeal. He asked the executives to begin their annual stockholder meetings by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance before attending to the business at hand.

The reward for his temerity? Half the corporations did not respond, and those that did shouldn’t have. Ford Motor Company begged off, claiming it was a “multinational corporation,” an identity it apparently repressed when it asked for and received a bailout from the federal government of the United States in 2009. The CEO of insurance giant Aetna labeled the request “contrary to the principles on which our democracy was founded.” Paper and consumer-products manufacturer Kimberly-Clark went hyperbolic, dismissing the call as “a grim reminder of the loyalty oaths of the 1950s.” Only one American corporation, Federated Department Stores, agreed to recite the oath.

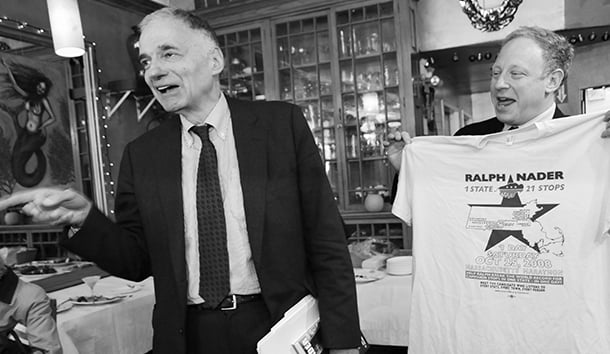

And just who was that modern day Lindbergh forcing his Trumpian agenda on the quislings of corporate America? None other than Ralph Nader. Perhaps Nader’s brief stint as a U.S. Army cook at Fort Dix inclined him toward such pro-American, nationalistic resentment despite his Princeton education and child-of-immigrants upbringing. Lucky for Nader his patriotic request predated the screaming hordes that have prevented the likes of Charles Murray and Heather Mac Donald from voicing other unspeakable truths at Middlebury, UCLA, and other bastions of closed-mindedness.

As it turns out, I opted not to drop the Nader bomb on the unwitting crowd. I had already burst enough pipe dreams that day just by broaching the concept of duty and by alluding to how Americans naturally acknowledge human and political connections outside the fantasy realm of Instagram or Snapchat. The school’s Protestant chaplain thanked me after the debate. Raised in the Midwest on modest means, he now subsists in New York City on $30,000 per year. My remarks led him to share a difficulty he had often encountered on our campus. Despite his pastoral training, he had trouble relating to the anxious, upper-middle-class student body’s disdain for lower-paying careers. I commiserated with his plight. But this time I found the courage to cite Nader, and did. I told him, as Nader wrote in his 2004 book The Good Fight, “We must strive to become good ancestors.” The pastor shook his head in knowing agreement. Unfortunately, we have no chance of earning Nader’s good-ancestor designation unless we first fulfill our duties as good American citizens.

Leave a Reply