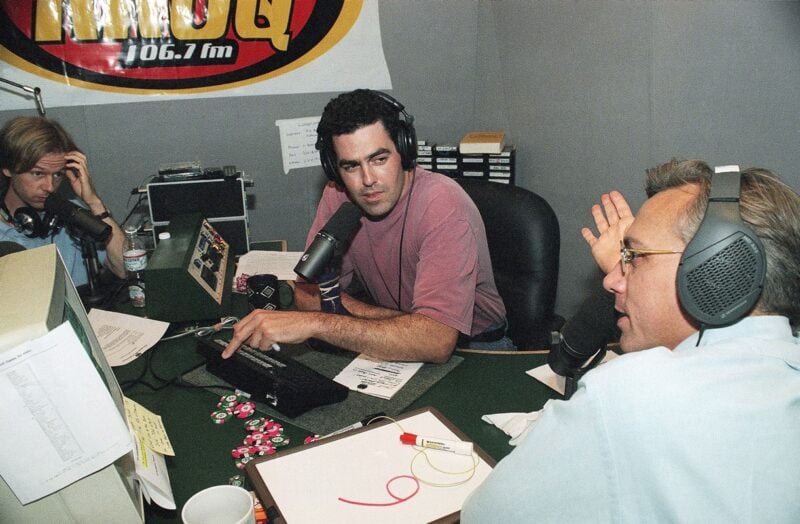

I first heard the Loveline radio show in the late ’90s. It came on late at night, broadcast from Los Angeles back to me in Atlanta. The format was like an old-fashioned advice column, but with a coarse edge. People phoned in with questions about sex and relationships, tales of abuse and heartbreak, disease and addiction. Hosts Adam Carolla and Dr. Drew Pinsky listened and gave guidance during the show’s heyday, from 1995 to 2005.

Except, that’s not always what happened—not even most of the time. Yes, some callers would describe a problem and the hosts would offer a solution: this boyfriend is bad and you should flee; those symptoms sound like an STD and you should see a urologist; get some therapy to deal with how your father acted, etc. The caller would pay attention, absorb the counsel, thank them, and hang up.

When those calls came on the air, you could hear relief in the voices of the hosts. A positive exchange with a troubled person, a man in Oregon who listens and pledges to act—wonderful!

A more typical dialogue went like one that I heard the other night (dozens of the shows are archived online—this one is dated May 27, 2002). “Rebecca,” a sober-sounding woman, checked in because her husband wasn’t happy with what was going to happen the next day. They hadn’t been married long—they were both 18—but there was a rift.

“I start a job tomorrow at a strip club,” she told the hosts, “and my husband is, uh, having a problem with that.” She avowed she “loves him dearly,” but said her husband was worried that she may come to enjoy taking her clothes off in front of other men. She insisted she merely liked to dance. How could she get her husband to relax?

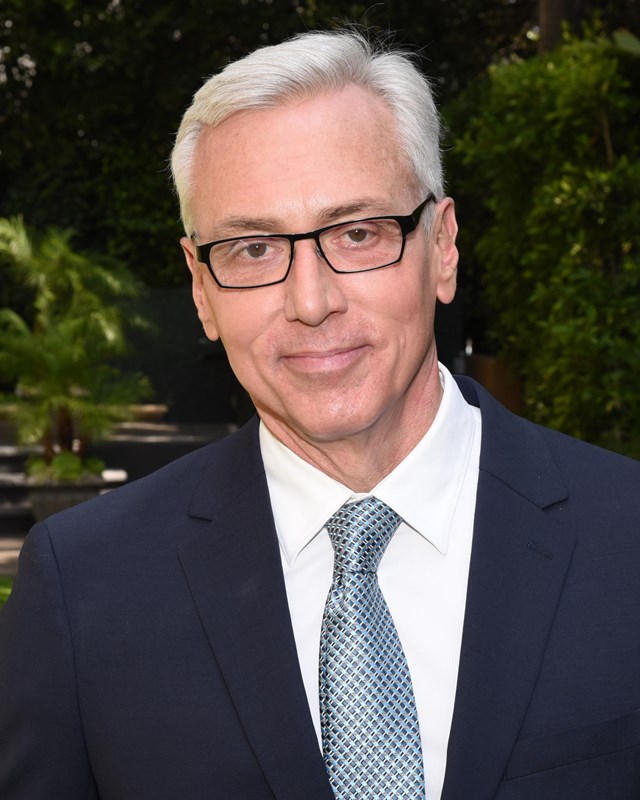

Dr. Drew is the medical advisor, a voice of professional concern, an expert in addictions and pathologies, and the author of books on dysfunctional behaviors. He preferred the questioning approach, this time verifying that she wasn’t surprised that he didn’t like it.

She admitted that his response made sense, but still probed for some way to calm him down and make him “feel better.”

“No,” Dr. Drew said quickly, shutting down her line of rationalization.

That was Adam’s cue. If she couldn’t follow a simple logical query from a doctor and realize how blocked she is, it was time for another tack: the Carolla Treatment.

Adam is the opposite of Dr. Drew: a Valley guy who played high school football and never earned a college degree. He relied on his background as a raunchy youth from a broken home to reflect on the messy lives of the callers. Drew was diplomatic, Adam politically incorrect. Drew gave medical opinions; Adam cracked wise. Drew identified them as depressed and bipolar; Adam called them “screwballs.” Drew referred to patients he’s had in the past; Adam recalled himself 15 years earlier, wasting hours in junior college, crashing on buddies’ couches, and laboring as carpet cleaner and construction worker.

Adam has written several funny memoirs about his early years, one of them entitled Not Taco Bell Material (2012), after a line spoken to him when he applied for a job at a Taco Bell outlet. He started in radio and got his big break in 1994 when he arranged a boxing publicity stunt for Jimmy Kimmel. He would go on to cohost The Man Show on Comedy Central in 1999, which showcased girls in bikinis bouncing on trampolines and men guzzling beer.

Adam took up the caller’s case with an enthusiastic idea for her husband. “You could give him, like, half off a lap dance and a drink coupon,” he suggested. She didn’t laugh.

Drew stepped in with a dose of reality, telling her that she is there to arouse men—that’s all. She insisted once more that she only likes to dance. Adam chuckled, Drew sighed, then Adam slipped into sleazy announcer mode, pretending to introduce her for the first time to a crowd of ogling men. Drew proceeded to the obvious point: why was Rebecca in such complete denial over what she was doing? Adam added, “Why are you screwing with him [her husband]? What’s wrong with you?”

Drew stepped in with a dose of reality, telling her that she is there to arouse men—that’s all. She insisted once more that she only likes to dance. Adam chuckled, Drew sighed, then Adam slipped into sleazy announcer mode, pretending to introduce her for the first time to a crowd of ogling men. Drew proceeded to the obvious point: why was Rebecca in such complete denial over what she was doing? Adam added, “Why are you screwing with him [her husband]? What’s wrong with you?”

She stuck to her story. “It’s a job. That’s how I think about it. It’s just a job.” Adam raised the issue of why she and her husband married so fast as two 18-year-olds, and Drew inquired, “What are you running away from, and why?”

“We wanted to get married,” she answered, a surly tone edging into her voice.

Drew repeated, “What are you running away from, and why?”

“I’m not running away from anything.”

“Alright,” Adam said, “then dance your ass off and explain to your husband why he shouldn’t care.” She stayed silent.

“You angry about something?”

“No,” she sniffed. The conversation hadn’t gone where she wanted it to go, and she wouldn’t go where the hosts suspected the real issue lies.

That was the pattern. A caller described a situation and posed a question, but the question sidestepped the real problem. And when Adam and Drew zeroed in on the core matter, the caller had to stop and think. She answered as if nobody had ever raised a query that the rest of us consider obvious and necessary.

A teenaged girl had just gotten her nipples pierced and wanted to know if that will hinder breastfeeding once she has kids. Drew wondered why she didn’t check on that before she did the piercing.

A 20-year-old girl told the hosts that she and a friend went to Vegas, met a couple of guys in a bar, ended up drinking in the guys’ room, and when they paired off for sex, her partner eased a beer bottle inside her as some kind of crude jest. It still bothered her, and she asked for suggestions as to how she could get past it. After Adam joked about long-neck and short-neck bottles, they told her to take it as a learning experience—and part of the learning is not to go to a complete stranger’s hotel room and drink!

Before they called, it seems these callers had never pondered how they bore some responsibility for the situations they’d found themselves in, and what their actions said about their underlying priorities. These internal contradictions and unquestioned assumptions they hold about life aren’t obvious to the callers, or even to the audience—until Adam and Drew pointed them out.

Again and again, the incognizance of the callers is stunning. A teenaged caller worried that his girlfriend’s mother doesn’t like him. Why? Because the mother caught the 16-year-olds engaging in oral sex in her bedroom. The boy asked how he might get back into the mother’s good graces. He can’t seem to acknowledge the fact that she now carries around a mental image of the two of them together that appalls her. Adam and Drew speculated, too, that the daughter, who initiated the act and left the door open with her mother down the hall, wanted to get caught as an act of rebellion, and advised the boy to stay away for his own good. The psychological considerations of the situation were beyond him.

Again and again, the incognizance of the callers is stunning. A teenaged caller worried that his girlfriend’s mother doesn’t like him. Why? Because the mother caught the 16-year-olds engaging in oral sex in her bedroom. The boy asked how he might get back into the mother’s good graces. He can’t seem to acknowledge the fact that she now carries around a mental image of the two of them together that appalls her. Adam and Drew speculated, too, that the daughter, who initiated the act and left the door open with her mother down the hall, wanted to get caught as an act of rebellion, and advised the boy to stay away for his own good. The psychological considerations of the situation were beyond him.

Another caller was a wife and mother of two kids. She and her husband regularly met with a married couple for a “foursome,” but she worried that the other wife had further designs upon her husband. Adam and Drew told her to forget the other woman, that the whole thing is crazy—to which she replied with a confused, “Huh?” She was so caught up in her jealousy, notwithstanding her sex acts with the other woman’s husband, that she couldn’t recognize the perversity of the whole situation. They had to yell at her to stop at once, adding that she was harming her children. “No, no,” she objected, “we’re really good parents!”

The pleas kept coming, one obtuse or deluded individual after another. The chaos in which they found themselves originated inside them, but they couldn’t see it. All too often, the hosts detected a strange aura about the callers—Adam says, “Drew, I’m getting some ‘energy’ here”—and they asked the caller what happened to him.

“What do you mean?” one such caller answered.

“Did someone do something to you when you were young?”

Nearly always a “yes” would follow, be it a rape, child abuse, or the mistreatment of an alcoholic parent. Adam and Drew proceeded to tie the caller’s current plight to past damage, but most of the time the caller could barely make the connection themselves.

A 21-year-old guy lived with a 28-year-old woman who had two kids from a marriage that broke up years before, after her husband beat her. He had grown close to the children, but she treated him like dirt. He’s obviously a nice guy and couldn’t understand why she was so cruel. He wanted advice on how to make her stop—as if this kid, barely out of adolescence, had any chance of controlling her and fixing her life. Their blunt advice to him—“You’re not going to change her, buddy”—left the deeper puzzle unsolved: what happened earlier in his life that had made him devoted to an abusive woman?

Most of them were hopeless cases. The hosts knew the callers would ignore the diagnosis. The woman who was angry at all men because she couldn’t find a good boyfriend wouldn’t recognize that her anger may have had something to do with it. The guy who wanted to remove a tattoo from his penis and fretted about the process couldn’t answer why he ever got a tattoo down there in the first place. The high school girl who hung out with guys in their mid-20s and joined in their weekend sex parties was incredulous when Adam and Drew insisted they were exploiting her. She believed they were her friends, and she said she’d stick with that notion.

Dr. Drew sighed and groaned. On a show I replayed this morning, he blurted at one person, “You’re not hearing anything!” Adam would rant at their stupidity, begging one caller after another: “Please, please, don’t ever have kids!” He told one who already had kids to send them up in a hot air balloon so that they’d float to another state and take up with a new family that would give the son a chance to avoid prison and the daughter to avoid the sidewalks of Hollywood Boulevard.

Back in 2000, my girlfriend at the time thought Loveline was ridiculous. We were professors living together and working on scholarly books. She couldn’t understand how I could waste the night hours listening to these human dregs go on about their pains. Everything in her northeastern prep school and Ivy League training taught her to stay away from screw-ups. People like us should transcend this squalor.

Up until then, I agreed. I didn’t grow up in a prosperous household and I never attended a private school in my life, but I gave the poor and dysfunctional credit for as much independence and self-awareness as everyone else. People make their own decisions, I thought. Get them educated, show them the right course, and they’ll choose rightly. Or, they’ll hurt themselves. Either way, it was up to them.

I was 40 years old, childless and unmarried. Family and fatherhood weren’t on the radar. I didn’t go to church or believe in God. I owned a small home but had no contacts with neighbors and belonged to no local associations. My country was just a place of residence, my university the thing that gave me an office and paycheck. No patriotism and no on-the-job loyalty. Reality was myself on one side and the universe on the other.

That was the case with Loveline callers, too. Adam and Drew asked them about their lives and backgrounds, probed for anything meaningful, anything to anchor the callers, but came up empty. I can’t remember a single happy churchgoer in the 50 hours I’ve listened to recently. Some young callers actually mocked their parents’ faith. They didn’t mention any teachers or coaches, either—no priests or wise coworkers. They had friends, yes, but those friends only added to the turmoil of their lives. The jobs they had were just jobs; they spoke of their work in tones of boredom. America had no more meaning to them than did the grocery store down the street. And, of course, the families they came from were cause for more pain than reassurance.

Merely by probing the cause of these callers’ dysfunctions, Adam and Drew turned what was supposed to be a raunchy radio sex-advice show into a catechism of conservative lessons. Every confused, blind, self-destructive, promiscuous, addicted caller was a testimonial to the importance of conservative values. The callers were on their own; they relied on their own meager resources in a world of lax sex norms and do-your-own-thing morality. They had slipped into depravity, and the traditional protections against it were missing from their lives. Worse, the world they occupied discouraged the very self-examination that is necessary to transcend it.

A teenage girl told the hosts about pain she suffered during sex and wanted to know what might cause it. She let slip that she was raped on a camping trip two years before after she got dead drunk and a guy coaxed her into his tent. When Drew asked her if she often drank that much, she muttered a casual, “No,” as if drinking herself into oblivion had nothing to do with what happened.

I just listened to one of the most frustrating callers of all: a 32-year-old single mother who liked marijuana and had two unstable boys, a 14-year-old who had exposed himself to his cousins and a 12-year-old who had been arrested for vandalism. She asked how she could make the older one stop doing bizarre things. Drew tried to get her to say in more scientific terms what is wrong with him. She muttered something about special education and denied she had ever used drugs while she was pregnant. Drew told her to have a neurologist evaluate him first—she needed a diagnosis. She mumbled a half-hearted, “Uh huh,” which prompted Adam to bark, “Stop smoking the weed and start mothering!”

I just listened to one of the most frustrating callers of all: a 32-year-old single mother who liked marijuana and had two unstable boys, a 14-year-old who had exposed himself to his cousins and a 12-year-old who had been arrested for vandalism. She asked how she could make the older one stop doing bizarre things. Drew tried to get her to say in more scientific terms what is wrong with him. She muttered something about special education and denied she had ever used drugs while she was pregnant. Drew told her to have a neurologist evaluate him first—she needed a diagnosis. She mumbled a half-hearted, “Uh huh,” which prompted Adam to bark, “Stop smoking the weed and start mothering!”

“I don’t smoke weed around my kids,” she countered.

Adam: “I don’t care—you sound out of it!” Drew remarked that he could hear the effects of long usage in her voice at that very moment.

She protested, “I have no problem doing my job as a mother.”

Adam reminded her she’s got a 12-year-old who has already landed in jail. She retorts that it wasn’t her fault, that the boy had broken windows while she was at work and that he was in his father’s custody at the time. Adam grumbled, “Okay, keep going; smoke more weed,” then cut her off and asked Drew, “Listen, can we have her sterilized?”

Liberalism can’t do anything with or for these people. They don’t possess the enlightened self-interest and rational choice that a liberal culture assumes its members should and will acquire. Without good fathers and mothers, exposed to wickedness at a tender age, with no trust in God, and with no devotion to country or community or workplace, they act out in bad behavior the losses a liberal society has handed them.

They want to fix their lives—that’s why they’ve called—but they don’t have the equipment. No religion, no role models, no patriotism or work ethic. They demonstrate more vividly than Milton Friedman ever did what happens to a fair portion of the population when a society of libertarian individualism loses its moorings in the conserving institutions of church, family, and nation.

Instead, liberalism offers them a career plan, an achievement focus. The elite tell them, “You just need more education.” But Loveline callers couldn’t envision that, either. After hearing one after another meander and stumble as they described their conditions, Adam would ask, “Caller X, what are you doing? What’s going on?”

“Huh?” he would reply.

“Where are you going?”

“What do you mean?”

“What’s your plan?”

“You mean right now?”

“No, jerkoff,” Adam would grunt, “I mean what are you doing with your life? What do you wanna be?”

Confused silence. They knew in some part of their heads that they should find a steady job, stop jumping into bed with bad people, avoid drugs and booze, and take care of intimates close by, but those obligations didn’t win out. They had no God, good father, or civic duty to command them. True, Dr. Drew frequently counseled therapy, but the therapy he had in mind wasn’t the once-a-week analysis and self-exploration of old. It was a program that would take charge of their lives, assign them a monitor, and restructure their behavioral codes. After a few years of despairing for the callers he encountered, even Adam, an atheist, started to suggest callers take up religion as a final resort.

Some conservative converts got there by reading National Review and Whittaker Chambers’ Witness. Others watched leftist comrades become too radical, or saw the Soviet Union collapse, or recoiled at political correctness. The Loveline caller made a different case. He demonstrated truths about human nature—the limits of self-determination, the insufficiency of private reason, the necessity of family coherence—that liberalism denies.

Liberalism has to deny these traditions that make up for human frailty in order to justify the sexual revolution and to ignore the cultural and social destruction that has followed it. Liberalism’s parade of human damage musters for roll call in student health clinics, women’s shelters, inner-city classrooms, in the streets of San Francisco and underpasses in Los Angeles, in divorce courts and public housing—and on the phone lines of Loveline, the best conservative radio there ever was.

Leave a Reply